(Editor’s Note: Elie Shamir, who is by profession an artist, wrote this article about the origins of Kfar-Yehoshua, a settlement in the Yezreel Valley of Israel, which inspired him to create a memorial to Richard Kauffman, the architect and planner who designed Kfar-Yehoshua.)

by Elie Shamir

elieshamir.co.il

First published in Cathedra brochure # 111

Translated into English by Adi Schilling

_______________________________________________________________________

COMMENTS and EXPLANATIONS

Introduction

In the following essay I wish to clarify the origins and the vision that are embedded in some aspects of planning the public areas in Kfar-Yehoshua, which is situated in the western part of theYezreel Valley. I suppose it is likely that any creation, even the most revolutionary and innovative one, is based in some way, or connected in some way to the history of art and architecture;1) every change is necessarily based on the tradition against which it is rebelling, and every plan somehow needs to be legitimised for the historic past as well as for the intentions and the realities of the present and the future. The past of Kfar-Yehoshua’s founders grows out of Eastern European Judaism,2) Judaism which is still holding on to tradition, and at the same time encountering general European culture. I wish to examine the enviromental planning of the village, the water tower, the communal hall and of the sculpture in memory of the fallen, and also to pursue the dialogue the designers developed with the history of art and with their personal biography. I shall try to clarify how the builders of Kfar-Yehoshua saw themselves by means of these very same creations. The location of Kfar-Yehoshua is considered here as the centre, as a point of concentration to the perspective of influences from different directions.

Historical Background

Organization A was founded in 1923 following the call of Yaakov Uri (Saslavski)3) for the establishment of the smallholders’ cooperative settlement of Nahalal B, this following the second Histadrut committee meeting which took place in 1923. Six young men in their twenties met in the tent of Naftalie Ben-Ner in Nahalal and announced the founding of the organization. 4) At this meeting nobody took any minutes, but some time later, in 1923, a document was drawn up which explained the aims of the organization in detail. In 1924, during the Shavuot holidays, the organization’s council met in order to clarify the ideological goals, and on the agenda were the ideas of the kibbutz and the kvutzah, together with the idea of the moshav that was expressed in Nahalal. ‘Our organization consists of a group of fellow members which finds expression of its aspirations in the individual and free farmer, together with the effort to make use of the positive aspects which are part of the collective settlement’, thus Ben-Ner summed up the committee meeting, by trying to combine the idea of the kibbutz with the concept of the moshav.5) In 1924 a contract for buying the Western Valley by “Chevrat Hachsharat Hayishuv” was signed under the auspices of Yehoshua Hankin, and on the 4th of January 1927, the committee of organization A met in Nahalal and decided to call the village in the name of Hankin. In a letter which the committee sent him, Hankin was informed that ‘it was with great pleasure that we decided to call the settlement in your name, namely Kfar-Yehoshua’ 6)

Some time later, on the 3rd of March 1927, the wooden hut of the former tenants of the railway station in Tel Shamam was brought to the hill of the village. The first families were housed in this hut and thus Kfar-Yehoshua was established!)

The Letter

The idea of a ‘Garden City’ was conceived by Avigdor Howard of Britain in 1898 in response to the extensive urbanization of the city of London, which according to him caused ‘urban pollution, poverty and the emptying of rural areas’.8) In the same year Howard established ‘The Garden City Association’ in order to further his ideas. He called on people to return to nature, our beautiful earth, the realization of God’s love for mankind.9) In 1902 Howard published his book “Garden Cities of Tomorrow” in which he explained his ideas of planning a new urban neighbourhood. It is important to mention that Howard suggested a comprehensive social change, and the urban planning was to include a new ideology. He emphasized that rural life was a healthy lifestyle, which encourages the connection of good morals and social values more than in the past.” The first Garden City, Letchworth, was built in 1903, and in 1919 an additional city, Welwyn, was founded. Not all of Howard’s ideas were realized in these towns, especially not the part of the co-operative and communal aspects which Howard saw as an integral part of the new lifestyle in the Garden Cities.

At the beginning of the century Howard’s book was translated into German. In Germany too, an “Association of Garden Cities” was formed and already in 1906 the first Garden City near Dresden was established. In Germany the project included the social ideals, and the Garden City was not only expressed in the style of building which emphasized the integration of buildings in nature, but also a place where food, clothing and lifestyle were supposed to be more natural. The architect Ernst May who was invited to rebuild Frankfurt after the First World War, knew the British idea of the Garden City very well, and claimed that the ‘the system is likely to strengthen efficiency at the workplace and to create a communal organization with a simple lifestyle’. 11)

The German-Jewish architect Richard Kauffinann, the designer of Kfar-Yehoshua, was invited to come to the country in 1920 by Dr. Arthur Ruppin, director of the settlement department of the Jewish Agency.12) After he had designed a suburb and houses in Germany, including buildings for the “Krupp” company in Essen, and even prepared plans for the Hungarian Royal family, Kauffmann was invited to design towns and villages in Eretz-Yisrael. Straight after his arrival in the country at the young age of 33, Kauffmann started to work strenuously. In Jerusalem he designed the suburbs Talpiot, Rechavia, Beit-Hakerem and Kiryat-Moshe13) and at the same time was busy planning moshavim and kibbutzim in the Yezreel valley. Altogether, Kauffman drew up over 130 urban designs, in addition to plans for single buildings and special projects, like plans for the electric company and villas, like the Prime Minister’s residence of today.

Kauffmann was-well acquainted with the idea of the Garden City: in the twenties he visited the Garden Cities in England and took a lot of photographs there. In the articles he wrote following his travels in Europe in 1926, he mentioned that he knew many of the Garden Cities still before the First World War, 14) and wrote thus: ‘concerning our country, one cannot imagine any form of settlement more suitable than this, from the practical, as well as from the social, socialistic, health, ethical and artistic point of view.” 5)In his plans Kauffmann tried to combine the idea of the Garden City with the Zionist—Socialist world view; the return to nature promoted by Howard could have been connected to the rebirth of the Jewish people through cultivation of the soil, according to the viewpoint of A.D. Gordon. Kauffmann even set his aspirations further than that. By means of his plans, and without them noticing, he influenced the Yezreel Valley settlers to have the chance for a better quality of life and leisure time activities long before these subjects were on the Zionist-Socialist agenda. In a letter written by Kauffmann in 1923 to Akiva Ettinger, head of the department for agricultural settlement in the Zionist Executive Committee, a letter in which he answered questions about the plans for Nahalal he wrote: ‘two parallel avenues which run from the communal hall centre and from the school to the bottom of the hill, from there an additional broad line of fruit trees around the ring of the moshav is being planned. This will make it possible to go for walks in the shade of the trees on Saturdays and in the future it will be possible to put up some benches for people to rest on.16)

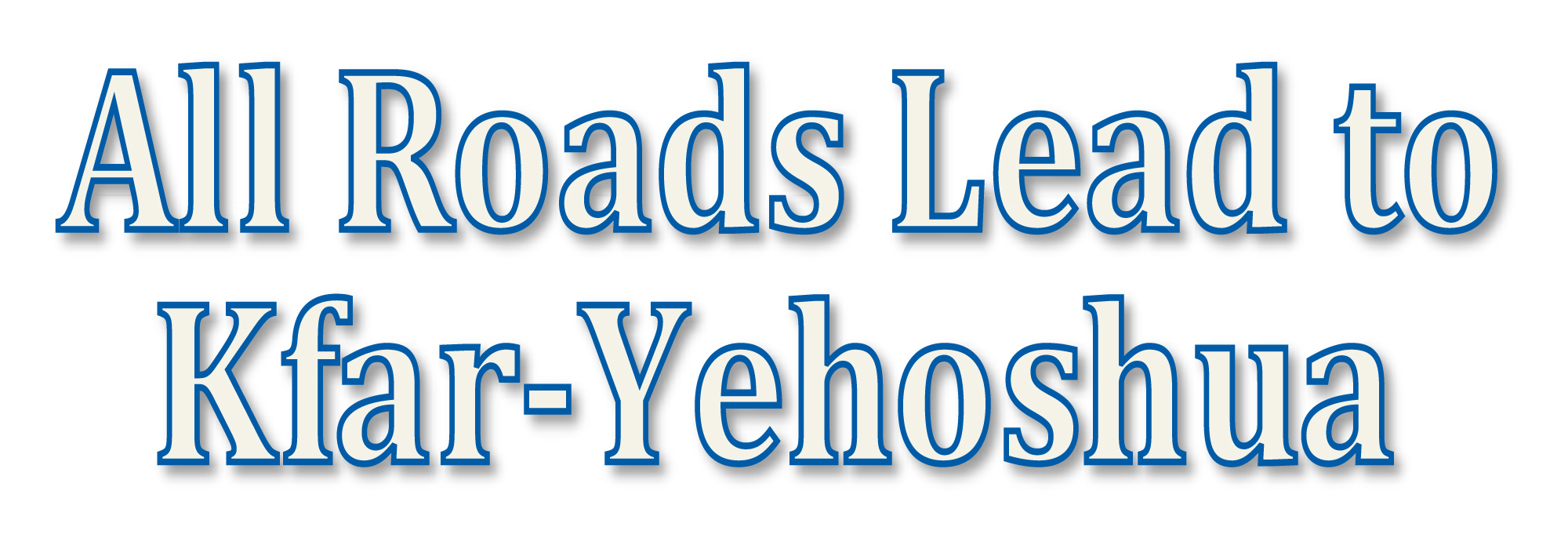

The people of Nahalal settled on the land in 1921. The moshav was designed in the shape of a circle (slightly flattened, like an ellipse) — a revolutionary design which came from utopian sources.”) The plan took into consideration the shape of the hill on which the settlement was situated — Kauffmann wrote about this explicitly in his letter to Ettinger – and also the wishes which the settlers expressed in conversations they held with Kauffmann. Yaakov Uri subsequently described the meeting of the settlers with Kauffinann and his attempt to get to the bottom of the concept guiding the moshav: ‘it is also fitting to mention the sincere attachment between the architect and his family and between the ’tillers of the soil’, for whom he designed their settlements. ‘His consideration of their opinions and his profound interest in their way of life — can serve as an example to everybody.’1 8) Through the synthesis of different ideas — the utopian design, the idea of a Garden City and the wishes of the settlers — Kauffmann created a pioneering concept of designing. He designed a new kind of agricultural settlement — the first moshav and the first kibbutz. He also designed the first dining-hall in a Kibbutz (Ginegar) and the first communal hall in a moshav (Nahalal), and thus continued to influence the lifestyle in the settlements he had designed.

The planning of Nahalal in the form of a circle stemmed also from an ideological point of view: the even distance of each farm from the centre of the village (the centre which is actually an axis and not exactly a point, because it is in fact an ellipse and not a circle) expressed the equality of the members of the co-operative society, the members of Kfar-Yehoshua who knew Nahalal very well, were well-aware of it, and therefore persevered in their insistance that the communal hall should be built exactly in the centre of the village.19) Elyahu Amitzur,20) a member of the third Aliya, born in 1903, and one of the last founders of Kfar-Yehoshua still with us, explained to me that the round design of Nahalal and Kfar-Yehoshua gave also expression to a feeling of security to the Jewish settlements in the area. The first agriculural border settlements like Kinneret and Tel-Chai were built around a courtyard, later on settlements were built along a road like Kfar-Tabor and Moshava Kinneret; these settlements had two entrances on both sides of a single road and defending them was comparatively easy. In Nahalal and Kfar-Yehoshua considerations of security did not restrict the plan and it was executed according to the vision of the planner. Those, according to Eliyahu Amitzur, were the “First Open Country Settlements”. Worthy of mention here is, that this thinking was in opposition to that of Percival Goodman who was convinced that Nahalal was a fortress just like a circle of wagons in a caravan.21) In my opinion Goodman was wrong: each farm in Nahalal or in Kfar-Yehoshua has its own entrance from the fields, which exposes the whole circle to attack from outside and from all directions.

Yaakov Lorch mentioned Kfar-Yehoshua in an article he published in honour of the 50th anniversary of the newspaper “Davar”,22)according to him the members of Kfar-Yehoshua had such a positive attitude, that even if the plan for the moshav was not in accordance with the needs of the inhabitants, similar to the elliptical planning of Nahalal, but in the shape of the letter ‘Yod’, it was in order to remember Yehoshua Hankin, the ‘Saviour of the Yezreel Valley Lands Amitzur who came to Kfar-Yehoshua in 1928, about a year after the land was settled, testified that he heard from the first settlers that the village was built in the form of a `Yod’. Also, from other people belonging to the first generation of settlers, it became clear that they and the next generation as well, grew out of this knowledge,23) even if there was no clear evidence that Kauffmann was asked to design the village in the shape of a letter, it was important for the settlers to be aware that they were living inside a big letter.

The contour of the village was in fact long, in the shape of the letter `Yod’, and even if this happened by chance, the builders of Kfar-Yehoshua chose- being Jews who knew the shape of a letter – to comprehend their village in this way. And this was no simple letter, the letter `Yod’ was there because of Yehoshua Hankin, but also in the name of God, even in his shortened name. I put this question to Amitzur and he responded: I hear this for the first time, I like it but I have never heard of it from the people of Kfar-Yehoshua and I never thought of it. It is possible that subconsciously there was something like this… .As far as I know God had no part in Kfar-Yehoshua (my feeling). Maybe when we were young we still had some measure of religious belief, but when they built a wooden hut for a synagogue it was built in order to serve the generation of our parents… 24) We realised that Kfar-Yehoshua was the realization of the Torah — the Torah of life and not an antiquated Torah… .The real holidays were evidenced by tilling the soil, the festival of Shavuot was there to celebrate the first harvest and not the festival of the “Giving of the Law”.25)

The builders of Kfar-Yehoshua could choose between the two letters `Yod’ in a sensible way: the one pertaining to God, as they had learnt in their paternal home, or the other, the Zionist, revolutionary and secular one, the `Yod’ of Yehoshua. The letter `Yod’ could also serve as a symbolic, traditional sign for a Jew — thus, for instance in the poem “the Point of the Top of the Letter Yod” by J.L Gordon (1876), or in the Jiddish weekly `Ra’ad Yod’ which was published in Poland in 1899. It seems that the letter suggested a number of possible choices which had serious meanings, but this choice was never made, at least not concsiously. The significance of the letter never crossed the mind of any of the founders, most of whom in their youth had studied in the `cheder’, maybe only subconsciously, according to Amitzur. It seems that the Torah influence of the paternal home was pushed back and the revolt against it was like erasing it. Nevertheless, from the words of Amitzur about Kfar-Yehoshua as the realization of the Torah, nothing disappeared the fight over the legitimacy by way of history or by way of the Torah remains.

In 1927 Abraham Schlonsky published the collection of songs ‘Gilboa’. In his poem “Hinei” (here) he depicted the pioneers of theYezreel Valley as those who inscribed God’s word on the parchment of the soil:

Here is my country, a wild corpse

It has a skin of parchment, parchment of the Torah

And an inscription nearly erased

God’s message on the parchment,

Who is the savage who can read the Megilah

Which is in the beginning?

And who will have the privilege to wrap the talk here

And to ascend to the Torah? 26)

Schlonsky, the way Dan Laor put it, expressed in this poem the essence of the spirit of the third Aliyah,27) ‘With being very personal in this poem’, wrote Lea Goldberg in the margin of one of the poems ‘Gilboa’: ‘there is no one more reliable than him in describing the spirit of that generation, in which Schlonsky is not the only one, but he is their poet.28)According to the spirit of the times, which was expressed in Schlonsky’s poem and in the words of Amitzur, ‘the creation of Kfar-Yehoshua did realize the Torah’. In the year Schlonsky’s book was published, the pioneers of Kfar-Yehoshua came to settle on the land, and inscribed on it the letter ‘ Yod’, ‘God’s word on parchment, the cultivation of the soil resembles God’s word on parchment and the pioneer who realizes this is the savage who will have the privilege to ascend to the Torah and read the Megilah Bereshit.

On the face of it Lorch was right – the ideology supplied a firm framework for everyday existence, and the decision on the shape of the village out of ideological considerations, seems spiritually appropriate. Nevertheless, in another essential matter he was wrong; the shape of the village was not forced on the settlers arbitrarily, but was to a great extent in accordance with the vital needs of the inhabitants.

Because the round shape of Nahalal was so complete and continuous, Kauffinann found it difficult to design an entrance to the settlement. People who entered the circle of Nahalal found the approach unwelcoming. The entrance is sudden, like an unbidden guest, straight to the inner courtyard of the village. In addition, the circle does not allow the organic expansion toward the outside – of course, there was also an advantage in this, in case the settlers wanted to restrict the number of inhabitants. Indeed, up to this day, no expansion whatsoever has been built in Nahalal, and the future expansion planned, is situated completely outside the circle, without any relation to it. Kauffinann was well-aware of all this and in his letter to Ettinger pointed out, that if it will be necessary, ‘to settle additional groups, special notice should be taken to build on the mountain ridge which is north of the road to Nazareth and which has particularly good conditions for the purpose of settlement’29) and with these words he pointed almost to the position where Timrat is today.

Kauffinann drew his practical conclusions from the criticism that was thrown at him regarding the planning of Nahalal and this was expressed in his design for Kfar-Yecheskiel which was established in 1922.30) In the design of this moshav he changed the eight pieces of the circle of Nahalal into an octagon, the southern slope of the octagon he opened in the centre and changed it into an entry road,31) In this way he indeed solved the problem of entry, but created serious problems with regard to parcelling the agricultural ground in relation to the farms, and difficulty in organizing the inner area in relation to the central line of entry.

When planning Kfar-Yehoshua, Kauffinann returned to the basic construction of a circle. The shape of the * Yod’ in Kfar Yehoshua is no more than the shape of a circle that is stretched from one end to the other.32) The tail end of the ‘Yod’ is the main southern entrance, and the tip of the letter – is the exit in the direction of Ramat- Yishai. In the plan the tail-end and the tip-end had some useful functions. Opening the tail-end downwards opened the circle and created preparedness and an invitation to come in, so that entry into Kfar Yehoshua was gradual. The southern fork, a square with bushes, together with the Obrotz grove, had two different possibilities of entry: one turning right towards the row of farms, and the other towards the center of the village33). The tip of the ‘ Yod’ enabled the comparatively organic development in settling the farmers’ descendants in the 1950′s, and today – the further enlargement of the village, also leading to the cemetery. The tower, the most important feature of the village stands between the northern and southern entrance. In order to retain the shape of the ‘ Yod’ Kauffinann divided the village into four non-equal parts, with the aid of four central axes stretching towards the center. These central lines acted as a kind of pivot; lengthwise Kauffmann stretched half the circle’s eastern half to the south and its western half to the north. These lines fit both the topography and the geography of the village. The axis, which runs from the center northward leads exactly to the north and is situated on the highest spot of the tower, on the watershed between east and west. The four central lines do not meet at the center in one place, but create an elongated rectangle. In contrast to the plan of Nahalal, in which the center of the circle was emphasized and there were difficulties in connecting new buildings to the circular form, in Kfar-Yehoshua the central axes were emphasized, and each one developed its character in an organic way. The eastern line, from the center eastward, is the axis of the industrial area, which is economically successful, lying next to the environmentally neglected area which is waiting for improvement: at the back of the co-operative store is a road in bad condition full of rubbish, the deserted building for building materials, the institute for alloys and the tool shed, and next to it a depleted and neglected avenue of trees. In contrast to this, from the center northward is the important axis which was planned well: two parallel lanes which cradle an elongated garden in their midst. Later on, the buildings I shall talk about further on, were built along the length of the avenue: the water tower, the memorial statue to the fallen and the communal hall, and also the grove planted between the garden of the memorial and the peripheral road. It is important to mention that Kauffmann planned a wide avenue on an exposed hill on which at that time, nothing grew, not even one tree, and he tried to realize his vision of a green avenue in European urban style. This and more, in many of his letters Kauffmann emphasized that central lines and lines that connected important landmarks played a significant part in the urban planning of Europe. Paris and Berlin were two outstanding examples of that. Kauffmann designed towns and villages at one and the same time and tried to create different combinations for these two ways of life. Next to the houses of Rehavia he tried the possibility of vegetable gardens, and in the plans for Kfar-Yehoshua there existed the option for a different, non-agricultural development. There was a big gap between the life of labour and of commerce, out of necessity and out of merit, between the pioneers of Kfar-Yehoshua and the vision for quality of life, which the avenue of Kauffmann represented. The design of the village, the same as the design for Nahalal before it, allowed large areas for the development in its setting. It is hard to exaggerate one’s appreciation for the boldness of Kauffmann who designed so many large public areas for the first settlers of the village. Amitzur confirms that this was really the impression the empty areas gave the setting.

The Water Tower.

Kfar-Yehoshua’s splendid water tower is situated at the highest point of the village, at the center of the avenue. It became clear that the ambitions of Kauffmann as a designer influenced the first settlers and this was expressed in the design and the building of the water tower. In resemblance to many ancient mythological objects, it is not known who designed the tower – the tower ‘came down from heaven or grew out of the earth’34) There is also some difference of opinion as to who was responsible for the building, but it is clear that the builders were the people of Kfar-Yehoshua, and they finished the work themselves in a most professional manner in 1929. The water tower is built on the basis of an octagon and has three floors: the first is the floor of round arches, half of it with high pillars (standing between the pillars can give one the feeling of standing in a cathedral), the second floor has low arches and the third floor is a round cement barrel divided into eight by protruding vertical cement strips, which continue upwards the line of the columns. On top of the third floor – a flat roof with a railing of short cement pillars. On top of one of the high arches on the first floor is the inscription in cement moulding, in the style of letters written like in the scriptures: 5689 and in the center of the inscription – a Star of David made of cement, above the peak of the arch. The arches were actually not necessary for the structure because it was built completely of cement casting, and the large expense incurred was exclusively for aesthetic reasons, and this at a time of poverty. The cut sections of the pillars are also not simple: each pillar has three layers of cement which are arranged like stairs similar to the pillars of a cathedral, and the middle layer carries the arch. The cast letters and the Star of David were for decoration only, and this surely gave the building a special Jewish-Zionist identity. Amitzur stated that when they built the tower, there was a feeling that this was an especially beautiful building: ‘we were lucky, that such a fine tower was designed for us when we just needed any tower whatsoever. Our tower is not like the one in Nahalal, when we built it, there was a feeling that we were building a structure that was reminiscent of the ancient synagogues in Eretz Yisrael, like the ruins of Rabbi Yehuda the Hasid in Jerusalem.

The connection of the Torah with fresh water is well known – ‘he will be like a tree planted in a stream9 is written in the Book of Psalms 1,3: ‘Like a tree planted by streams of water’ about the righteous – but why was the water tower designed in classical Italian style? In Europe one can find classical buildings which have several floors. Many public buildings were built with three floors: the ground floor which had round arches as partitions, a second floor of lower arches, and a third floor without arches. Even the Colosseum in Rome was built on the same principle of doubling the Greek temple in height, although the Colosseum has three floors with arches and only the fourth floor is divided into rectangular squares without arches. It is important to point out that in the Colosseum the arches were necessary for the construction, whereas for the water tower of Kfar-Yehoshua they were built, as mentioned before, only for aesthetic reasons. In any case, the similarity between them and the arches of the Colosseum and many Renaissance arches in churches and castles are easy to recognize. The classic period and more than that the Renaissance period which creates anew, out of awareness, the classical culture, is characterized by social, cultural and economic progress, and mainly by a feeling of optimism and meaning.35) This is the heart of the matter. Feelings of optimism and purpose were not lacking in the first settlers of Kfar-Yehoshua. ‘This I accept with both hands’ said Amitzur.36) Indeed, a society in which there is an atmosphere of optimism, purpose and a feeling of renewal like in times of Renaissance – is likely to generate from inside, art works with a classical character, as it happened in Kfar Yehoshua. The tower with the arches, and in addition to the mould with the letters Tarp”t (5689) and the Star of David, is likely to remind one more of a temple than any other water tower in Israel.37)

The Communal Hall.

For eighteen years the water tower stood in the center of Kfar-Yehoshua before the cornerstone for the building of the communal hall was laid. Already in 1937, following the donation Hankin had made to the settlement, the first meeting was held with Abraham Harzfeld and Hankin in the matter of building a communal hall and a nature house in the name of Hankin.38) On a simple steel plate on the front of the communal hall was consequently written: “this communal hall was built in memory of the late Judith and Amitzur Krause, in order to fulfill the testament of the late Yehoshua Hankin in whose name our village was called”. Many discussions were being held among the settlers as to where the communal hall should be situated, mainly because they demanded to build it at an equal distance from the members’ houses and not at the site that Kauffmann had planned. Despite many discussions and voicings of different opinions, they did not manage to reach an agreement, and in the end the decision was transferred to a committee of Nahalal members39), and according to its recommendation the communal hall was built on the site which Kauffmann had specified, and that is where it stands today .40)In determining the location of the communal hall, the connection to the Garden Cities which Kauffmann had designed in the suburbs of Jerusalem and in other places, was clearly established that in fact public buildings in a Garden City will generally be built on the highest point at the end of the garden axis.41) The topographical facts were also taken into account in Kfar-Yehoshua – the avenue which comes to its southern end next to the communal hall is placed at the watershed of the village’s hill, and runs exactly north-south.

The committee of Kfar-Yehoshua turned to a well-known architect Dr. Gideon Kaminka,42) who designed a pretentious and large building facing the water tower. Apart from a sketch in handwriting, showing one of the facades of the water tower, signed by Kaminka, one can find also a letter congratulating Kfar-Yehoshua on its tenth anniversary on 25th July 1937, in which he wrote:* I wish to send you my heartiest congratulations; I am very glad to have had the opportunity to partake in the work of developing the village through the communal hall building. Would that and this plan will be realized soon and will give a pleasant ending to the period of the first decade. ‘43) Building of the communal hall started a decade later in 1947, and was completed on the 25th September 1948.44)

The design of the communal hall was influenced by the international European style, which is characterised by clear interaction between simple geometrical forms, and thus it is also in the communal hall, but this is only the point of departure. This institution was of great significance as its name indicated: its location clearly expressed its designation, to be the home of the people, in which public life was concentrated; discussions and meetings concerning the village and gatherings for happy and sad events. All the holiday and wedding ceremonies took place there and even the coffin of a member who had died was laid out in the communal hall and not in the synagogue. In this case the coffin was laid out on benches opposite the main entrance and the people passing it entered through the side door and exited through the main northern entrance to the cemetery.45* According to the vision of the village fathers, the people were the source of authority and in this respect the communal hall was the substitute to parliament or synagogue, institutions which the founders knew very well and hid well from the second generation (it is interesting to note that the communal hall for topographical and geographical reasons I mentioned before, points south towards Jerusalem similar to the synagogue). For some years a joint Passover Seder was conducted in the communal hall, with new texts which came instead of the “old” ones and also a chapter that was prepared for Independence Day.46)

A pillared porch closing a rectangled garden that looks like an outside patio leads to the entrance of the communal hall. On the front, above the entrance there is an ornament etched in the plaster, the handwork of Sverin (Saive) Malkewitz (1913-1969), a member of Kfar-Yehoshua, which portrays the ‘people’ and their various occupations: agriculture, education and culture. Veterans of the village remember the walk in festive clothing (white shirts), from the various neighbourhoods through the dark streets to the area of the center, and from there to the lane of the dimly lit pillars covered with climbing plants. The passage through the patio of pillars created an atmosphere of intimacy demanding mutual connection, up to the entrance through the doors, which were too narrow, and so people were aware of the empty space in the communal hall on which they opened. The communal hall was designed as an elongated space divided lengthwise into three sections: the middle section with a high ceiling and on both sides areas with low ceilings resting on two round massive columns on each side. The floor of the structure was built as a sloping paved plane, which comes down in southerly direction and leads to the stage, and the center of the ceremony or play.

In the communal hall too, the basic principles and signs of recognition of public building with ancient roots were also realized – the Cardo, old synagogues and the Christian basilica. The potential of the communal hall as a Cardo was realized when stands were put up in the low sections and the central open space was used as a dance floor. One can also add that the Cardo in the Roman city was always in the north-south direction, and that too was the exact direction of the communal hall Kaminka certainly discerned the similarity of the building he had designed to a basilica, and created a basic difference between the two. The basilica is in the form of a cross which is created by two arms which come out of the two sides of the rostrum bisecting the long axis of the building. In contrast to this Kaminka placed the protruding arms in front, and in this way made it possible to lengthen and emphasize the front and the entrance. Also, the entrance through the corridor of pillars was showing great authority. An entrance shaped in this manner is very rare but in Rome there is something similar, namely the pillared entrance to the Church of Saint Petrus in the Vatican, the most important building of the Catholic Church, built by the sculptor Bernini (in the years 1656-1657); its famous cupola was designed by Michelangelo.47) Bernini designed an enveloping elliptic entrance and emphasized mainly its inside in the center of which was the sundial. The designer of the entrance to the communal hall was interested in an intimate passage which continues through the row of pillars. He even used a diversion similar to the one Bernini had used; the pillared entrance of Bernini is not a perfect circle but an ellipse in which the short diameter is placed at the entrance to the church. A person standing in front of the pillared entrance has the impression that it is a perfect circle, and therefore lengthens it mistakenly because the entrance to the church seems further than it really is and one thinks that the building is bigger than it is in reality. The rectangled corridor of pillars of the communal hall is likely to create a similar illusion.

There is a small synagogue next to the communal hall. The synagogue serves as a meeting place similar to the communal hall. Formerly, it was impossible to compare the big and imposing communal hall with the small synagogue. The communal hall was a place giving new legitimacy in which the people were the source of power. In contrast, the synagogue was for many years considered by local standards to be an anachronistic remnant of ‘grandfathers’, (Sabaim in the language of the locals) and some ‘residents’ -in contrast to the real settlers – who still had not internalized the character of the new Israeli. And behold, the synagogue is still functioning and a special committee is looking after its affairs. Whereas the communal hall lies in ruins, as a tangible expression of the deep rupture that befell the new Israeli. In place of the communal hall they built a functional and pleasant clubhouse, but this cannot and does not replace the original communal hall.

The Memorial

By the end of the War of Independence and the return of most of the soldiers from the Palmach and the Israel Defense Forces, a heavy shadow was cast over the village because of the loss of those who did not return.48) A committee was established including the families of the fallen, Eliezer Shulami (1902-1989) and Yehudith Ankori (1902-1972) and representatives of the village Eliezer Simchoni (1900-1969) and the teacher Menachem Saharoni (1912-1979), who according to Amitzur was the moving spirit of the project. All four members of the committee were from the first generation settlers of Kfar-Yehoshua. After extensive tours to places of commemoration in the country, it was decided to erect a statue sculptured in stone. The sculptress Batya Lischansky (1900-1992) who received the Israel Prize in 1985,49) was chosen to execute the work. Lischansky was requested to show her design and this was chosen after the sculptress showed a number of sketches and a small model in plaster of Paris to the committee members. The stone for the sculpture, a clay stone of large dimensions and weighing 35 tons, was mined in the Galilee by Avad Alhamid Suavi Abu Ganem (1876-1969), and the stone was handed over to the sculptress in 1950.50) The sculptress worked on the preparation of the sculpture in Kfar-Yehoshua, with the help of one assistant approximately fourteen months.

The expenses for loading and transporting the stone were donated by Solel Boneh, but the settlers, and this in times of poverty, took it on themselves to finance most of the projects. The pedestal on which the statue stands is covered with panels of marble on which the names of the fallen of Kfar-Yehoshua and the names of the Youth Aliyah youngsters are inscribed, as well as the symbols of the Palmach, the State and the dedication. Amitzur, who lost his son Amihud in the War of Independence, at first had reservations as to the erection of the memorial, but at the same time, the differences of opinion did not affect the feelings of love and respect between him and Saharoni. Amitzur even answered Saharoni’s request and wrote the epitaph which is engraved on the northern side of the pedestal: ‘in memory of those who built with their own hands and those who came to help and fought for the establishment of the State of Israel’. The inscription, in letters written like those of the Scriptures, was engraved by Zalman Lorber (1911-2001) the brother of Esther Orian of Kfar-Yehoshua. Lorber also designed and engraved the letters on the second memorial which was also erected by Lischansky, to the north of the first one and on which the names of additional fallen soldiers were recorded. The sculpture was dedicated on Memorial Day for the fallen of the Israel Army in 1953, with almost the whole population attending, including President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi and his wife Rachel Yanait, sister of the sculptress.

Lischansky, like any other artist, could not and surely did not want to create an ordinary sculpture. Precedents from the history of sculpture in general, and commemorative sculpture in particular, were known to her and she was wise to absorb their message for her own creation, which was designed accordingly and was connected to the present time and place. The sculptor Auguste Rodin finished his sculpture ‘The Burghers of Calais’ in 1895, a sculpture that surely was known to Lischansky. The sculpture memorizes a historical event in 1347. Six residents of Calais which is in France, chose to make the supreme sacrifice in order to save their town from the siege which/Edward the Third, King of England, had imposed on them. The English king demanded that the six, barefoot, dressed only in a shirt and a hangman’s noose around their necks, shall hand him the keys to the town and the fortress. The story of the citizens ended happily as King Edward pardoned them, but they were actually prepared to make this great sacrifice, and Rodin showed them on their last walk toward their expected death. With the sculpture in memory of the soldiers who fell in the War of Independence, Lischansky also portrays the readiness to fight, the resoluteness of the characters through their movements carved in stone. Like Rodin, Lischansky put one figure on the side, the last one which looks back, and this figure holds a plough in its hands. Indeed, Rodin separated the figures, each one to his own sacrifice, but the character that looks backward is easily recognized. Like Rodin, Lischansky was also influenced by the sculpture of the Pieta by Michelangelo, but in the memorial in Kfar-Yehoshua, the influence of the freed slave sculpture is especially noticeable. The struggle of the slave to emancipate himself is connected to the struggle of the figure to free itself from the prison of stone, and similarly to Michelangelo, Lischansky succeeded in establishing a wonderful affinity between the movement of the body and the substance of stone. The memorial came to symbolize the generation of the War of Independence ‘the last generation of slavery and the first generation of redemption’ in the words of Bialik in ‘Mati Medaber’ (Matti is talking), the connection to the freed slaves of Michelangelo is aimed at this. The statue reflects further European influences: the Marseillaise by de Lisle on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris and the heroism of the socialistic realism – but enough is enough.

The conventional semblance of the figures reminds us also of ancient Assyrian sculpture which in those times influenced the Canaanite movement. The Canaanite influence is of particular importance, especially when it is placed in opposition to Talmudic Judaism which created its image in the Diaspora free from Christian Europe and its sculpture. Amitzur also insisted on dividing the memorial into two parts: the Jewish part, the lower altar on which the names of the fallen were engraved and above it the part of the sculpture which shows us as being like all other nations. All this was concentrated in the excellent sculpture of Lischansky to one inner necessity, the movement in the material that gave meaning to her creation. There certainly is importance in the fact that the nursery school of the village is situated opposite the memorial, the children of the village thus being exposed daily to a work of art of such a high standard.

Conclusion.

Kauffmann planned Kfar-Yehoshua with the idea of the Garden City. It was designed in the shape of the letter ‘Yod’ and my opinion about its importance was expressed above. I identified the stylistic origins of the water tower, and most important, compared the shape of the tower to the Roman Colloseum and the buildings of the Renaissance, and connected these sources of influence to the optimism, feelings of ability and strength of the first settlers. The shape of the communal hall is also a combination of different influences that were used for their purpose as the center of public life in the settlement: next to the international style one can notice the influence of the Basilica and the Cardo and also echoes of the entrance to St. Peter’s Church in the Vatican which Bernini designed. I connected the sculpture of Lischansky to Rodin, to Michelangelo, to Canaanite culture and some other sources of influence, and tried to find out the significance of all these in the design of the sculpture.

Kfar-Yehoshua is the model for a village which is made in the mould of its builders and its designers, Jews who were rebelling against Judaism and the European Diaspora, who had brought with them their Jewishness and Europe to the soil of the Yezreel Valley.51} Kfar-Yehoshua actualizes the sentence which Tchernichovsky coined: ‘Man is the sum of his homeland’s panorama’ – and with this, one can also claim the opposite – ‘the panorama of a new homeland is the sum of its settlers!”

_______________________________________