By H. Rau

Editor’s Note: This document was created by scanning the original newspaper article and applying Optical Character Recognition (OCR). The British spelling was kept. However, the layout has not been preserved. The article is in two parts. Dr. F. Schiff authored the second part, titled “Villages, Towns and Regions”. The article was a tribute to Richard Kauffmann, and was published a month following his death on February 3, 1958.

________________________________________________________________________

DURING the last years ofhis life, Richard Kauffmann did not plan much, did not build much, did not say much. On his 70th birthday, last year, it was hard to tell whether his position in life was rather to be envied orregretted in those last years. Now, looking back at the lost opportunity it is easy to decide; it was regrettable for us, enviable to him. His lifelong dream had come true and he lived in the Jewish State. Consulted frequently, appointed to key public commissions, he had the opportunity to state his opinion and contribute of his sound judgment to the endeavours of the young and immature State of Israel, yet at the same time to remain at a comfortable distance from actions whose irresponsibility is very seldom admitted. Since he thus kept himself in the background, his passing might have been expected to arouse little stir. But just the contrary happened. We feel, that we have lost more than a chance; our sorrow is not just a bad conscience at having neglected him. His passing marks the end of an important period of Palestinian/Israel planning and architecture.

Irreplaceable Loss

Some time ago, Kauffmann was asked to write the history of planning and architecture among a people returning to its homeland. I do not know whether he started writing or was still busy with compiling dates and documents; at any rate, the work was not completed. This is an irreplaceable loss. Despite the tradition of contempt of younger men for the “eclectic ways and banal behaviour” of the older generation, Kauffmann had, throughout his life, a deep personal respect for men of his profession everywhere. His hand could have presented us with a generous and understanding picture of men like Baerwald, Geddes or Frank Mears; his book would have analysed the stillborn endeavours to resuscitate in this country a pre-World War I bourgeois architecture whose remains are still to be seen in Tel Aviv and Haifa, and it would have told the full story of the serious, careful and understanding personality of Arthur Ruppin, re-counting the ways in which this first-rate economist advised the agriculturist and the planner to “translate the idea and the plan of communal settlement into reality.”

Kauffmann’s history of the planning of agricultural settlements since its beginnings and the modest expansion it first underwent in the twenties would have shown how Kauffmann himself out of experience and tradition, looked at the realities of his country. Most justifiably, he considered our present-day planning as ten years of error and waste. Wholly honest and true to his profession, he refused to lend his hand or his reputation to such procedures. His name remained connected to the sound roots of this country’s planning and building, sunk in the cooperative work of sober idealists who knew their job.

Modern Approach

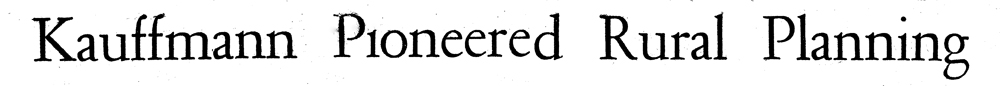

Dead Sea potash worker’s quarters, portrait, natural cooling building design for elementary school and regional plan for Haifa Bay area illustrating Richard Kauffmann’s wide range of talent.

Since we cannot read the country’s planning and building history in Kauffmann’s own writing, we must do our best to find out what it really was that makes us feel that his passing was so great a loss. Kauffmann arrived in this country at a time when modern architecture — not to speak of planning — was not yet accepted in Western Europe, when it was still considered revolutionary and not too respectable. At the same time, even modernists were far from the recognition that architecture (that is modern architecture) has to be realistic, structural and free of medieval or machinistic romanticism. Kauffmann arrived in mandatory Palestine as a child of that period in which ideas were partly realistic and partly romantic and modern forms were considered ends instead of by-products. From this point of view he recognized the vanity of forged bourgeois architecture, but though seeing the beauty of Arab architecture, he overlooked its reality. Basically realistic, he tried to cope with the difficulties of the climatic conditions on “modern lines,” and thus achieved his really great revolutionary feat: the well-shaded houses at Degania and those on the shore of the Dead Sea. Just in the same way, he tackled the planning problems of Haifa and located an open town in the Bay, with a main access from the east, and a bypass to the north, sound principles for whose utter neglect we will pay in the nearest future. At the very time he was turning out these, his real achievements, eclectics imitated and copied Arab forms of building in the weakest of manners. Most probably, since he was himself a real child of his time and thus a romantic modernist too, the realities of the traditional building in this country were hidden to him behind its romantic beauty.

Kauffmann made the best use of his own approach, developed his own personal style out of his own feelings with professional skill and knowledge. His plans and buildings are never vain, always true to topography and landscape or material and use, No traces of improper strange or vain fashions or influences stain his work. His last building, a children’s home near Romema, built by him through the initiative of Mr. Novomeysky, is an outstanding example of modesty in building and thus bears witness that Richard Kauffmann remained true to himself and his profession.

Villages, Towns, Regions

By Dr. F. Schiff

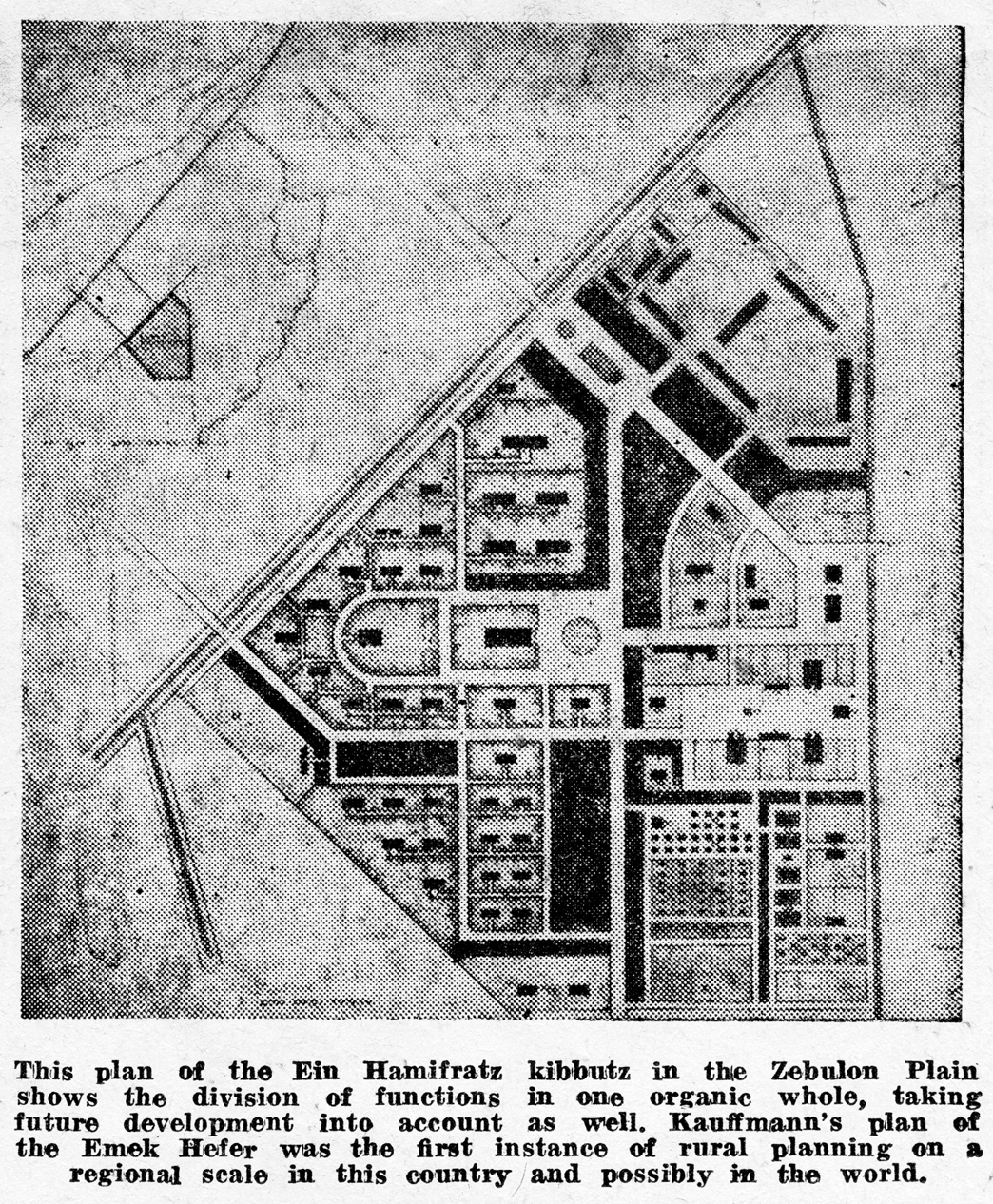

Town planning and of late regional planning has become common the world over but village planning on any large scale was introduced in Palestine long before any other country. When Kauffmann introduced it 37 years ago, it was a wholly new departure. Generally speaking, villages are the product of a lengthy historical process; they are made up of clusters of homesteads, either grouped round a church or market-place, or strung along the banks of a river or a main road. Our old-new land posed a new problem. A fixed number of settlements had to be established, each under absolutely identical conditions, and to be erected within the shortest possible time. In this connection, Kauffmann concentrated on the three cooperative types of settlement, the smallholders’ village (Moshav Ovdim), the large communal settlement (Kibbutz), and the intermediate type — the Meshek Shitufi. To plan them according to their individual requirements in the social and economic sense was his aim. Accordingly, each typical design has its special characteristics.

The Smallholders’ Village

Kauffmann started with Nahalal, a Smallholders’ Village, in 1921. In a settlement of this type, where every family has its own homestead, public and communal buildings should be so located as to be easily accessible to all. With this end in view the hillock is selected as the focus of the village. Following the contour line of the hillocks, Kauffmann constructed a road running round its upper part. The farmhouses are situated on the border of this oval. A second central ellipse girdles the grounds at the back of the farmhouses, and the whole is rounded off on the outside with a green belt. Inside the inner oval, with its Community Centre, School and administrative offices, Kauffmann placed the dwelling houses of the teachers, artisans and clerks. This particular design so perfectly suited the landscape and the social structure of the settlement concerned that it became the pattern for the smallholders’ village up and down the country. In the forties, Kauffmann used a similar design for Beit Yosef in the Beisan Valley, but there, for reasons of security, the style is somewhat more rigid.

The Communal Settlement

At the same time Kauffmann turned his attention to the Kibbutz and the Kvutzot, whose layout differs fundamentally from that of the Smallholders’ Village. According to Kauffmann, the essential thing is to keep the various zones apart and still preserve the unity of the whole. Consequently, he separated the residential zone of the grown-ups, with their dining hall and communal centre, from that of the children with their school, also the workshops and storerooms, and both from the respective zones allotted for the poultry runs and the cow-sheds. Wherever feasible, a narrow green belt marked off the different zones.

One of the main problems confronting architects in this country is the climate. Kauffmann tackled it by opening his houses to the north-west to give access to the prevailing breeze. The farm buildings, on the other hand, are sited towards the east, so that the wind should not blow from them to the living quarters. Incoming and outgoing traffic is kept separate from internal traffic.

From the very outset Kauffmann recognized the danger of the rigidly uniform design. In every single case, therefore, he sought to do justice to the distinctive features of the landscape and of the settlement concerned. In 1921 Kauffmann started with the layout of Kvutzat Geva, following it up shortly afterwards with the twin settlements of Ein Herod and Tel Yosef.

Among the other numerous kibbutzim planned by Kauffmann let us mention the outstanding layout of Maoz in the Beisan Valley, with its dining-hall situated in the centre of the settlement. In nearby Kfar Ruppin, one of the two hillocks is utilized for the cultural centre, the other for the school, which gives the settlement its distinctive appearance. In Dan, Kaufmann was able to carry out his demarcation of the various zones to the full. There the workshops separate the cowsheds from the poultry-runs, whilst the lawns and gardens between the dwelling houses, also in a separate zone, are oriented to-wards the Hermon. This is more than a purely aesthetic consideration: the view is bound to have a profound effect on those who work and live in sight of this impressive mountain range.

The Meshek Shitufi

The many personal problems arising out of group life have lately given rise to this form of cooperative settlement. Here, too, Kauffmann blazed a new trail. The individual dwelling houses have to be organically related to the communal buildings. In Moledet, established in 1937, Kauffmann therefore again took advantage of the raised ground in the centre to place on it the public garden, the school and the community centre, thus making the public amenities easily accessible from all parts of the village.

Town and Regional Planning

This is a less thankful task than the layout of cooperative settlements, because in the latter the land is a fixed factor made available by the settlers and/or the national institutions. In towns it is a variable factor, depending sometimes on the stiffness of the public bureaucracy, always on the fluctuations of private speculation in land, with the result that when the architect plans for a town, he knows that only part of his ideas is realizable. For these reasons Kauffmann always battled for a better order of things. We know how many unique opportunities were irretrievably lost in the planning of our large towns. Some of Kauffmann’s plans show what might have been done. Today everyone is aware of the overcrowded state of Haifa, of the bad communications between the town and its port — the most important on the western seaboard of the Near East. Kauffmann’s plans show that only a short 30 years ago the expansion of the town could have been directed towards the Kishon Plain across the artificial barrier of the Carmel shoulder. Had that been done, Haifa would have had for its centre the plain to which cooling breezes have free access. At that time already Kauffmann conceived the idea of shifting the railway line and constructing a by-pass by means of a tunnel through the Carmel range, leading approximately from Khayat Beach in a north-easterly direction; that would have directed traffic, including the railway line and would eventually have formed part of the land route from London to Cape Town, by-passing the town.

No less instructive was Kauffmann’s plan for a part of Tel Aviv stretching from Allenby Road to the present Gordon Street. In a seaside town attention should have been focused on vistas opening westwards to the seas. The first line of dunes immediately behind the beach should have been reserved for bathing and recreation, and the whole part shut off from all traffic by means of a wide green belt. The design further illustrates the folly of having levelled the low dunes instead of placing on their ridges public buildings to serve as gravity centres for certain selected groups of buildings. It is regrettable that Kauffmann’s many valuable suggestions were ignored.

Affula in the Emek Yezreel is still one of the dreams which have not come true. The idea that gave birth to it was that the growing density of population in that region would call for a country town as its natural centre. Situated just on the watershed between the Mediterranean and the Jordan basin, it was to be of circular shape, strung on the Haifa-Damascus railway line which was to pass through a cutting below the level of the town.

One of the plans executed in their entirety is that of the garden suburb of Beit Hakerem near Jerusalem. It was designed to harmonize with the natural rock terraces, and with the Teachers Training College crowning the central elevation,. The park is laid in a depression where the soil is deepest.

One of the main problems of architectural design in this country is the climate with its high summer temperatures and its heavy winter rainfall occurring in a relatively short period. This implies considerable use of insulating devices — above all, Kauffmann maintained, for the roof; for in summer the sun’s rays fall almost vertically at midday, heating the roof more strongly than the walls. On the other hand, adequate protection against the rain calls for a very expensive asphalt covering. Cork, pumice-stone and gas concrete as insulating material are also costly. Thus, when building the school at Degania in the hot Jordan Valley, Kauffmann hit upon the idea of mounting a Ternolit roof on a light wooden structure two metres above the ceiling proper, so as to allow the wind to circulate freely between the two roofs and exercise a cooling effect on the schoolrooms. The idea proved a success. The classrooms remained relatively cool. The Manager of The Palestine Potash Works who saw the building in Degania promptly invited Kauffmann to construct similar buildings at the Dead Sea.