Editor’s Note: This article was published in the Jerusalem Post on Friday March 20, 1959, a year following Richard Kauffmann’s death. It was written by Ariel Kahane.

_______________________________________________________________________

As early as 40 years ago Arthur Ruppin was well aware of the urgent need to bring to the Zionist Commission at Jerusalem a man who could give tangible and permanent form to the dreams that were part and parcel of the Jewish settlement of Eretz Yisrael. In this capacity Richard Kauffmann, who died just a year ago, served during the main part of the Mandatory period and after the founding of the State, always ahead of others, at once representative and pioneer. At the start, his was an isolated position: those surrounding him hardly understood the point of his vision and ideas; he ended up as the grand old man of a whole generation of town and country planners who continued working on their own along the lines he had traced for them.

Born in Frankfurt-on-Main in 1887, Kauffmann studied architecture and town planning at a time when the latter art was only in its beginning. He had proved his independence in it before World War One, when he participated in the planning of workers’ settlements for the Krupp plant in Essen. They were considered one of the best projects of this kind at the time. During the war he secured a first prize in the competition for a development plan for the city of Kharkov, and after the war he was selected from a large number of competitors for important town planning works in Norway. It was then, at the outset of a brilliant career, that Kauffmann was called here by Ruppin to direct the town planning projects which were to be an integral part of Jewish settlement in this country.

First Planned Kvutza

At the time this connection was far from a matter of course, and the solitary planner was deprived of the facilities he needed to establish it, as well as of the understanding of his colleagues. Yet he understood the challenge and proved equal to it. For the first time, villages and agricultural settlements were systematically planned by an architect — an epoch-making step that has only recently been imitated in other countries. In his plans Kauffmann combined the necessary technical and security aspects with the main intention, namely the mould (sic) for a new kind of communal living.

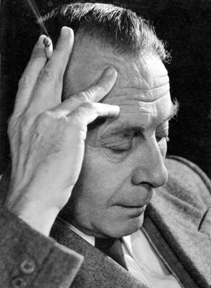

The first kvutza planned by Kauffmann was Geva. In 1922 he produced the work that won international popularity — Nahalal, cited over and over again in professional literature as the paragon of a village laid out by an architect. There followed a host of settlements, among them Kfar Yehezkiel, Ein Harod, Tel Yosef, Hanita, down to his last work, the expansion of Degania.

Above all Kauffmann loved his plans for agricultural settlements, where he made his most important and most personal contributions. In these plans he was guided by his communion with nature, without consulting which he would never touch a planning project. He loved and understood a single plant as well and as deeply as a whole landscape, and planning meant to him feeling and interpreting the surrounding region, the specific climate of the place, the type of landscape. He never made a concession to any style en vogue against nature’s harmony.

Planned Afula

Kauffmann also planned many of the quarters which form the centres of Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, Ramat Gan and Haifa, although their present appearance is far from his original intentions. Despite the warm appreciation of the Yishuv and its institutions, as well as the Mandatory authorities, he was unable, being but an individual, to overrule the many vested interests that arose during the later part of the Mandatory period.

Kauffmann’s vision of the ideal home and garden in Jerusalem has been preserved in unspoiled form in the upper part of Rehavia, where he did the town planning and also created many of the houses and their model location on the grounds. He also designed the first systematically planned city in Palestine, Afula. According to his plan the town was to develop around a representative city centre surrounded by blocks of flats, then to decrease in density towards the fringe of the town. The progress of the Emek town failed to materialize for several reasons, such as scarcity of water and the unwillingness to support a town out of its hinterland, at least outside the coastal plain. But these factors are hardly to be laid at the door of the town planner whose pseudo-realistic critics liked to cite Afula as an instance of utopian planning. At any rate, it was much more sensible to plan a town from the start as such instead of urbanizing prospering moshavot, as was the practice in the thirties and forties.

Kauffmann’s masterpiece in the field of regional planning was his plan for the development of the Carmel-Haifa Port-Bayside-Acre area. This far-sighted conception was granted recognition by the Colonial Office in London and found its echo in international professional periodicals. But no one was there to carry out his proposals: the means of the Yishuv at that time were inadequate and the ability of the Mandatory administration too limited.

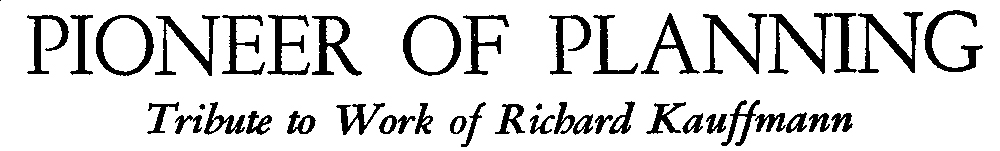

During the whole of his activity Kauffmann also designed private homes and public buildings, on which, in fact, he mainly had to depend for his income. Like the settlements he designed, they were guided in their design by considerations of climate and surroundings on the one hand, and artistic and personal points of view on the other. Never sensational or loud, they nevertheless always expressed his special style in their proportions. Among the private homes he built, Kauffmann especially liked the big house he created for the banker Aghion, today the residence of the Foreign Minister, in contrast to the style of neighbouring Beit Schocken.

University Campus

The Jewish sector was then putting up few public buildings or groups of houses, and therefore Kauffmann had a limited field of activity in showing his abilities in grouping them. He did some work of this type, for which he had a definite leaning, for the Hebrew University; the grouping of the buildings on Mount Scopus, as well as on the new Campus, is based largely on his work.

Kauffmann never held a teaching position; nor did he write much. But neither of these activities was foreign to his personality, and many of our representative town planners were influenced directly by him as they passed through his office, working with him for some time. He moulded (sic) public architecture in yet another way — by the weight of his opinion on the juries that selected winning entries in architectural competitions.

Kauffmann’s artistic approach and the method of his office are characterized by the high quality of graphic rendering in his drawings and perspectives. Therefore it seems fitting that his graphic legacy, which is professionally and artistically as well as historically important, is to be handed over to the Zionist Archives.

Richard Kauffmann was a trailblazer for his profession and his country.

Yet it was unavoidable that the ideas he represented became common property and were followed out by younger men who no longer pondered the fact that Kauffmann had been their mentor. After independence, he continued to be recognized as the profession’s dean but was no longer offered the scope of work that would have satisfied him. To the new generation of planners who had to find solutions for much wider and more complex tasks than before, he was ready to give his advice and constructive criticism; but these were taken only partially. After a rich life of full recognition, this disappointment darkened his last years. It is not enough that his memory lives on for his friends and colleagues: the official histories of Zionism and Israel architecture will have to give an appropriate place to Richard Kauffmann.

ARIEL KAHANE