Editor’s Note: This article, by Eliezer Brutzkus, was published in the Jerusalem Post on February 12, 1968, ten years following the death of Richard Kauffmann. The photo icon in the title block has been replaced with a version of the original.

________________________________________________________________________

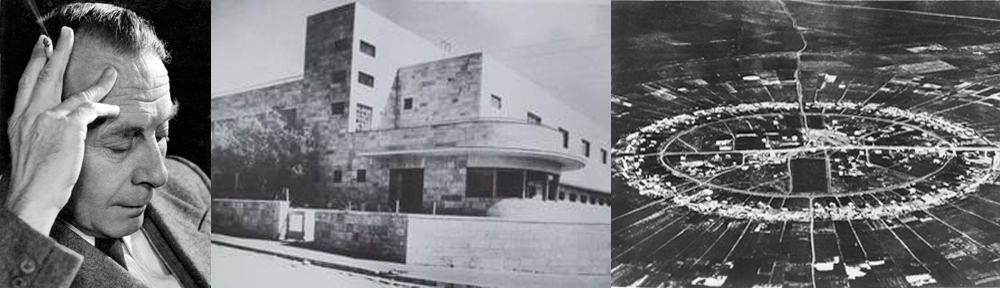

TEN years have elapsed since the death of one of the men who perhaps more than anyone else has left a lasting imprint upon the physical features of our towns and villages. Architect Richard Kauffmann was a pioneer of planning in this country and undoubtedly “the” town planner of its Mandatory period.

He came from Germany, and made his first mark in town planning in the ‘Ukraine during the First World War and later in Scandinavia. In 1920 the Zionist Organization, renewing its colonization work, invited him to Palestine to create lay-out for the new rural settlements. It was an attractive assignment, but for a town planner a most exceptional task.

The shape of a village is in, most countries the outcome of a slow, spontaneous evolution, and was at the time scarcely a subject of systematic and deliberate design. Here the peculiarities of the climatical, agricultural and social setting of the Jewish colonization work in Palestine had to be taken into account. This entirely new and complex problem required also awareness of the requirements of an agricultural society, of social, hygienic and security demands. Visual impressiveness had to be achieved as well.

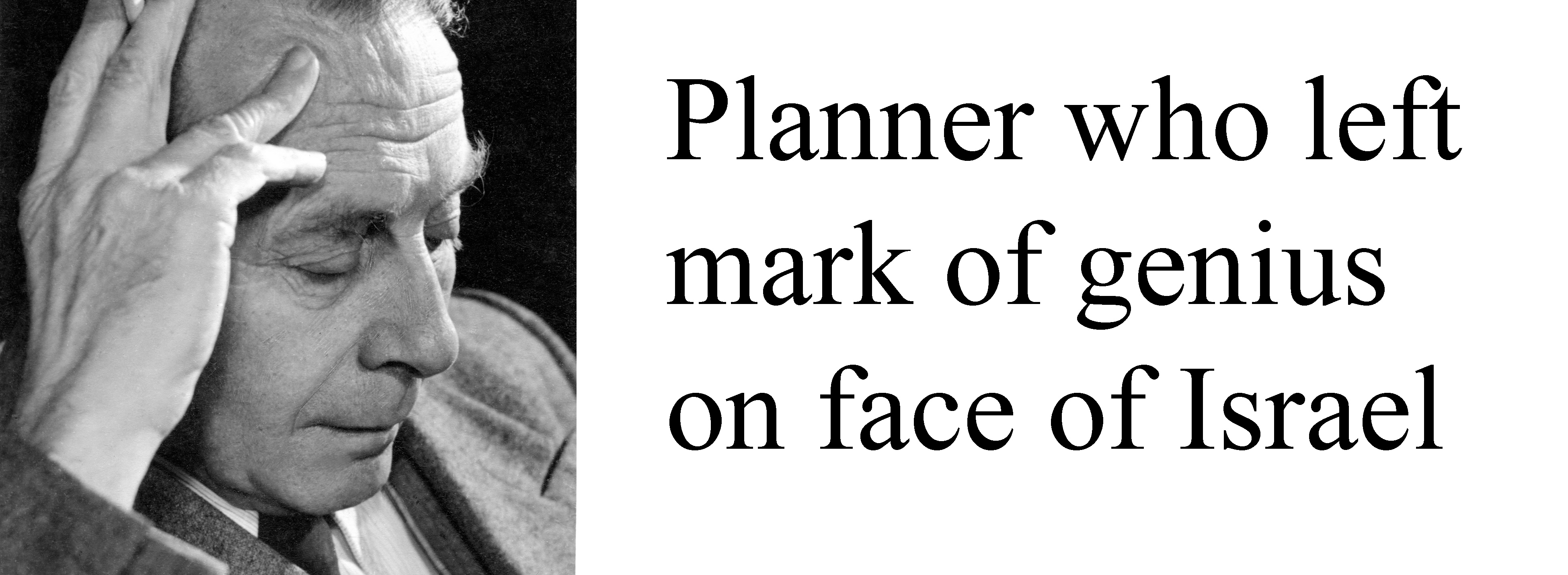

The Nahalal plan (1921) — a prototype for moshavei ovdim — was the outcome of Richard Kauffmann’s struggle – with the new problem: an ellipse approaching the circle where farmers’ houses were grouped along a circular road, their holding; stretching in facet shape towards the periphery, while the interior of the ellipse was occupied by plots for artisans and the common institutions of the moshav. Soon followed the lay-outs for Geva and Ein Herod, serving as prototypes for a kvutza and a larger kibbutz, with dining-room serving as focal node of the settlement on the line where the residential quarters and the farm buildings of the kibbutz met.

Most of the rural settlements founded in the ‘twenties and ‘thirties by the Zionist Organization and Jewish Agency were designed by Richard Kauffmann on similar principles, paying in every case careful attention to the peculiarities of the site and the agricultural and social settings of the planned settlement.

In the case of Emek Hefer (1932), Richard Kauffmann made a first attempt In Palestine at regional planning on a small scale providing a coherent plan for 14 settlements occupying a more or less compact area of 30,000 dunams.

The pioneering role of this country in developing designs of rural settlements is well recognized in the world, and Kauffmann’s Nahalal plan is often produced in handbooks for town-planning appearing in different countries.

But the activities of Richard Kauffmann were not limited to rural settlements. He worked, too, as an architect, designing buildings, and above all in urban planning. The basic layouts of Ramat Gan, Herzliya, the Rehavia and Talpiot Quarters in Jerusalem, of most of the residential quarters on Mount Carmel and of many other urban settlements, quarters and neighbourhoods derive from Richard Kauffmann.

His planning style reflects the general attitude of the revival of urban design in the first decades of the century, a reaction against the rigidity, dullness and monotony of the lay-outs of most cities drafted by surveyors and civil engineers. Kauffmann’s style was strongly influenced by the British “garden towns” movement.

A special gift of Richard Kauffmann was to know how to adjust his design to the peculiar details of the site and topography, never attempting to violate or to disregard them. This subtlety and genuine respect for the nature of the site semis today – in the age of the bulldozers and a return to more rigid and purely functional patterns of design – to be indeed “romantic” and even exaggerated.

The town planner rarely has decisive influence on the ultimate fate of the quarters and settlements he designs and actual development or misdevelopment has often altered, dwarfed and spoilt many of the careful designs of Richard Kauffmann. Nevertheless, the basic features of his layouts may be still recognised in the present Ramat Gan or Talpiot. They will be so for decades ahead. The imprint of the genius and skill of this cultured and personally charming artist is firmly engraved on the physical face of Israel.

ELIEZER BRUTZKUS