Editor’s Note: The spelling of “Kaufmann” should be Kauffmann throughout the article. Likewise, Lotte Cohn’s name was misspelled “Cohen”. The British spellings have been retained, but the original format was not. Also the article picture (above) was replaced by a photographic version with lower contrast.

________________________________________________________________________

CARRYING with him the Iron Cross and shrapnel wounds he had acquired as a German soldier at Verdun, and a continental reputation as a brilliant young planner, Richard Kaufmann abandoned Europe in 1920 for the wilds of Palestine to indulge a dream and begin a new life.

By the time that life ended 25 years ago last month, he had virtually single-handedly shaped the character of the rural sector of the Jewish state, created some of its most successful garden suburbs, introduced modern architecture, and laid the basis for physical planning in the country.

When he died at the age of 71, poverty and bitterness were hovering in the near distance as Kaufmann was bypassed by a new generation of planners and decision-makers; but much of the dream had been fulfilled.

Residents of more than 120 kibbutzim and moshavim owe much of the quality of life they enjoy today to Kaufmann’s design for their settlement. Residents of Jerusalem’s Beit Hakerem, Haifa’s Carmel, Ramat Gan, and more than a dozen other neighbourhoods enjoy the parks and streets he laid out. The prime minister of Israel is among those living in a house Kaufmann designed.

Renouncing bourgeois values, Kaufmann never owned a house himself. He died in a rented apartment on Abarbanel Street in Jerusalem’s Rehavia, a neighbourhood he had designed. Much of the money he had earned he gave away, and there was little left at the end. “All his life,” says 89-year-old Lotte Cohen, who worked with him as an architect, “he was the young man who wanted to build up the country. He was naive and enthusiastic. He was a pioneer till his death.”

Born in Frankfurt in 1887 to an assimilated family — his father had renounced his strict Orthodoxy after another son had died — Kaufmann hoped to be an artist. A sketch of the town of Dachau he made before World War I hangs in his widow’s apartment in a Jerusalem home for the aged. His father, however, insisted that he learn a profession and Richard studied architecture and the new profession of town planning in Munich.

HE BEGAN his career in Essen, designing workers’ houses for the Krupp works under one of the most esteemed planners of the time, Prof. Georg Metzendorf, who wanted to take the talented young man on as a partner. However, a painful love affair led Kaufmann to quit Essen in 1913 and try to forget his disappointment in travel. In Holland, he met Mies van der Rohe and others engaged in the search for a modern architecture.

With the outbreak of World War I, he left love and architecture behind and joined the Kaiser’s army on the Western Front. He was wounded at Verdun when he led a group of comrades trapped in a valley to safety through the French lines. Transferred later to the Russian front, he apparently worked there as a military architect and even won first prize in a Russian architectural competition for the design of a “garden community” near Cracow. When the war ended he made his slow way back through the chaos of Eastern Europe, arriving in Frankfurt only in February, 1919.

Almost immediately, he learned that a large planning firm in Norway was seeking a planner and he was chosen from among 50 candidates. Within a year he had won several prizes but he abandoned this promising future when he received a letter from Dr. Arthur Ruppin of the Zionist Executive inviting him to come to Palestine to design the new communal farming settlements the Zionist movement was beginning to establish.

It was a challenge to thrill any ambitious young planner. Town planning existed as a profession but there was no such thing as village planning. Villages grew spontaneously at crossroads or out of some other circumstance but were never planned. Now, however, the Zionist leadership was preparing to build scores of villages, in the form of communal agricultural settlements, to absorb the European immigrants coming to Palestine “to build and be built” by turning to the soil. Since these city-bred newcomers would be unlikely to succeed as independent farmers, the solution was to build communal settlements such as the pioneers had developed at Degania and a few other sites before the war. Unlike Degania, these would be carefully planned.

Aside from the professional challenge, Kaufmann had been an ardent Zionist since his youth. He had been a member of the Wandervoegel hiking society until it expelled its Jewish members. The leader told Kaufmann he could stay, but the young man quit and founded the Frankfurt branch of Blau-Weiss, the first Zionist organization in Germany.

IT WAS to Degania Aleph that Kaufmann went first shortly after his arrival in this country. “I found it a perfect example of incorrect planning,” he said later. “The wind blew from the garbage dump to the barn, bringing flies and odours, and from there to the kitchen, where it picked up the cooking smells and brought this whole mixture to the dining hall and living quarters.”

The visit led him to recognize the importance of the country’s prevailing west wind and to site houses so as to exploit its cooling effect while placing odour-producing elements downwind.

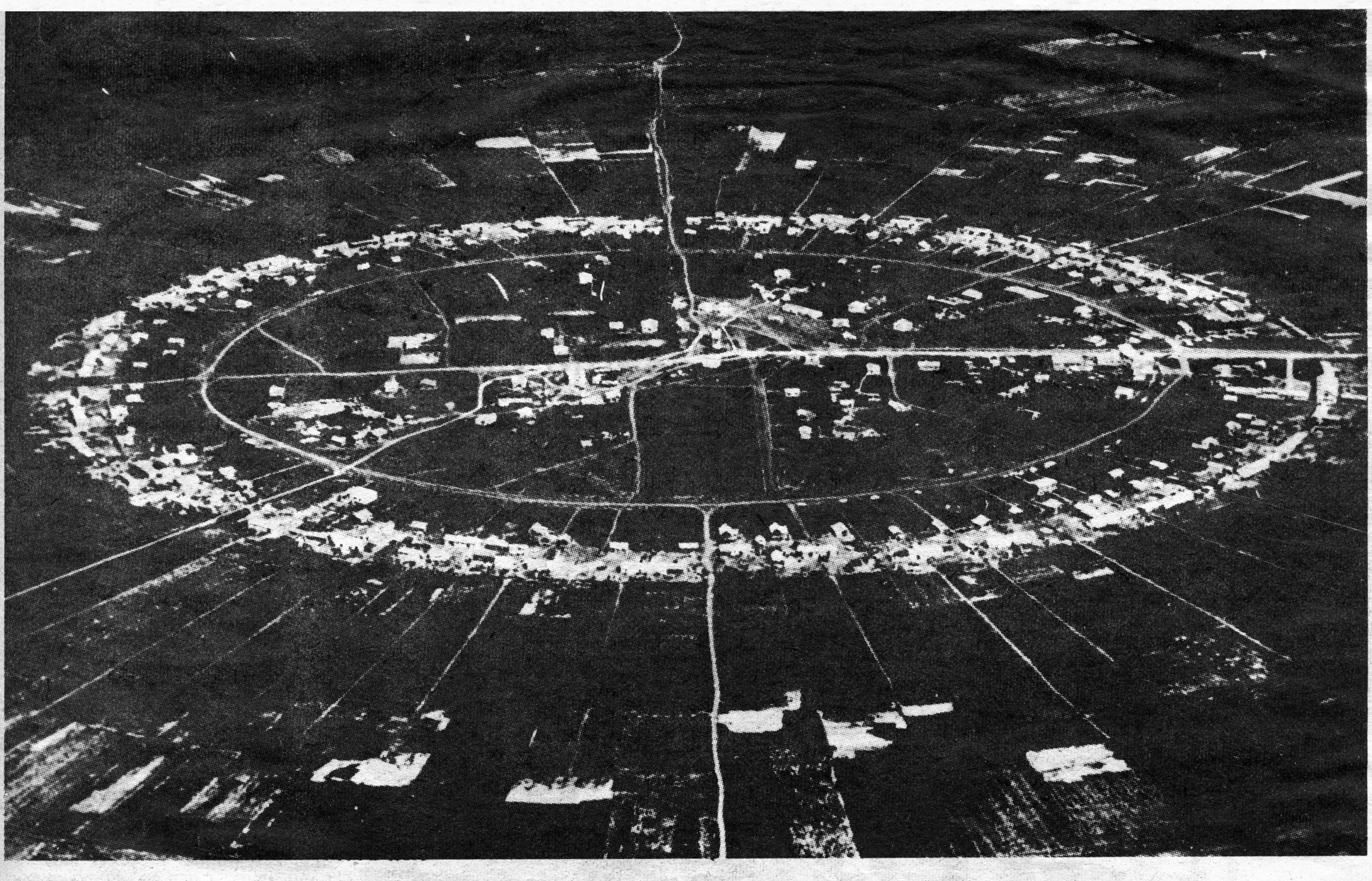

The first settlement Kaufmann planned was to be his most famous — Nahalal. Lotte Cohen still remembers riding across the empty Jezreel Valley with him to the foot of a hill where they were to meet the two main founders of the first moshav. The breakaway group from Degania, including Moshe Dayan’s parents, wanted to live a collective life less rigid than a kibbutz commune.

Kaufmann decided to make the hill the focus — symbolic and physical — of the collective by placing there the toolshed, office and other components serving the entire settlement. The farmsteads were placed in a ring around this core, the tracts of land radiating outward behind each farmhouse like pie wedges.

Although this striking design was to make Kaufmann internationally famous in planning circles, Lotte Cohen believes the design proved too rigid. “It is not the best of his work.”

Kaufmann next moved down the Jezreel Valley to plan his first kibbutz, Geva, and was soon travelling regularly between his Jerusalem office to the Jezreel, Beisan and Jordan Valleys to look at the sites of new settlements springing up. These journeys into the countryside were important to him spiritually as well as practically. “He loved and understood a single plant as well and as deeply as a whole landscape,” wrote a colleague.

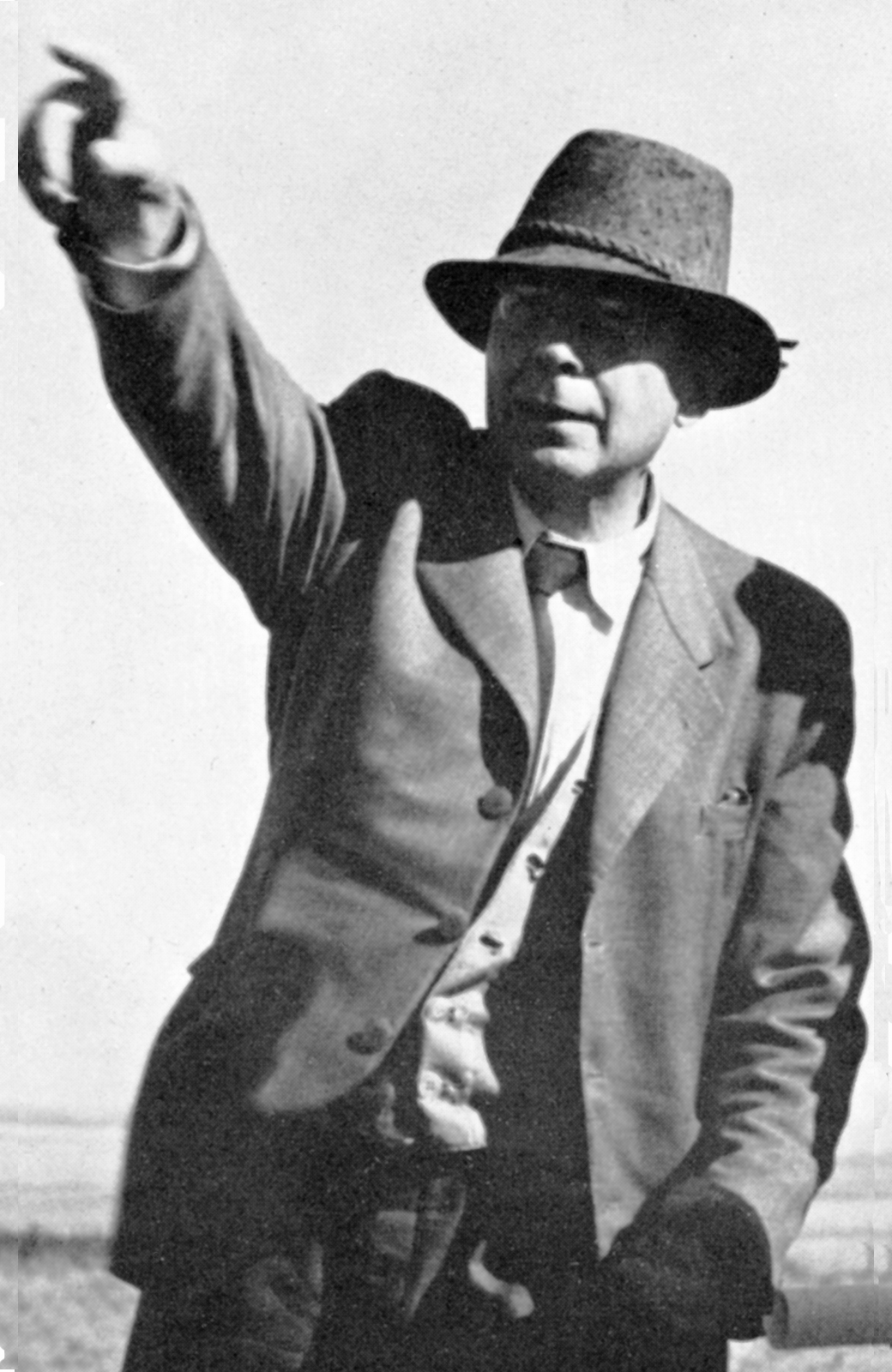

“In this country it’s impossible to do your planning at a worktable,” said Kaufmann in 1936. “Someone like me who has built 120 sites has to go out again for the 121st to see the land and the people. At the risk of sounding mystical, I must say that the decisive inspiration — much more important than experience — comes to me each time from contact with the ground on which I will build and with the people for whom I’m building.”

PROBABLY nowhere else in the world did physical design stem so directly from abstract ideology. Kaufmann’s home in Jerusalem was frequently filled with kibbutznikim and moshavnikim discussing children’s houses, cooperative marketing systems, or other communal aspects that Kaufmann has to translate into physical terms.

Kaufmann’s own style of living was so Spartan that these visitors often ate at his table two to a plate — at least in the early years.

“He lived very simply, in a way primitively,” recalls Lotte Cohen. “He loved company and was a very friendly person, but there was almost no furniture in his house. He didn’t want to be a bourgeois. He wanted to set an example of doing without. He made a lot of money, but he gave it away. If a new settlement needed a cow, for instance, he would buy it one.”

His family, which includes two daughters, also remembers him giving away much of his money to needy friends. He had left the employ of the Zionist executive a few years after his arrival in the country and opened his own planning office, continuing his settlement work on a contract basis. At one time his office employed 12 people but when work fell off sharply during the 1936-39 Arab riots he did not fire anyone.

ALTHOUGH he turned increasingly to urban planning and architecture, rural design remained Kaufmann’s primary enthusiasm, particularly when this was reflecting a new kind of Jewish society that he ardently admired.

“While the farmer in America or South Africa is happiest when from his doorway he cannot see his neighbour’s chimney,” he said, “the Jewish [farmer] wants to live close to his colleague. His need for personal contact and conversation with others, and especially his high cultural needs — for lectures, discussions, music, theatre, reading, chess — oblige the builder to place in the centre of each settlement, large or small, a cultural hall. This special Jewish need, together with other principles, makes for the special architecture of a Jewish settlement.”

Among these “other principles,” the veteran soldier met the need for security by seeking elevated sites for the settlements dominating their surroundings and ensuring at least one stout building in the centre of the settlement in which the settlers could hold out if necessary.

With his plan for the Emek Hefer district, he introduced the concept of rural regional planning in the country, an area in which Israel has remained an international pacesetter. He drew up a plan for Afula, whose prospects as an important urban centre were never fulfilled — and did a much acclaimed plan for Haifa — directing the town’s expansion towards the Kishon plain — which was never implemented.

However, many of Kaufmann’s designs for “garden suburbs” marked by greenery and pedestrian ways took shape. The one he was fondest of was Jerusalem’s Beit Hakerem. Among the other neighbourhoods he designed in the capital were the old Romema, Rehavia (north of Ramban Street), Talpiot, Kiryat Moshe and Bayit Vegan.

Among the Haifa neighbourhoods he designed were West and Central Carmel, Ahuza, and Neve Sha’anan.

If Degania Aleph reflected rural non-planning, Kaufmann saw in Tel Aviv its urban counterpart. “The town was not built according to a coherent plan and shows all the serious defects [of] such anarchic procedure.”

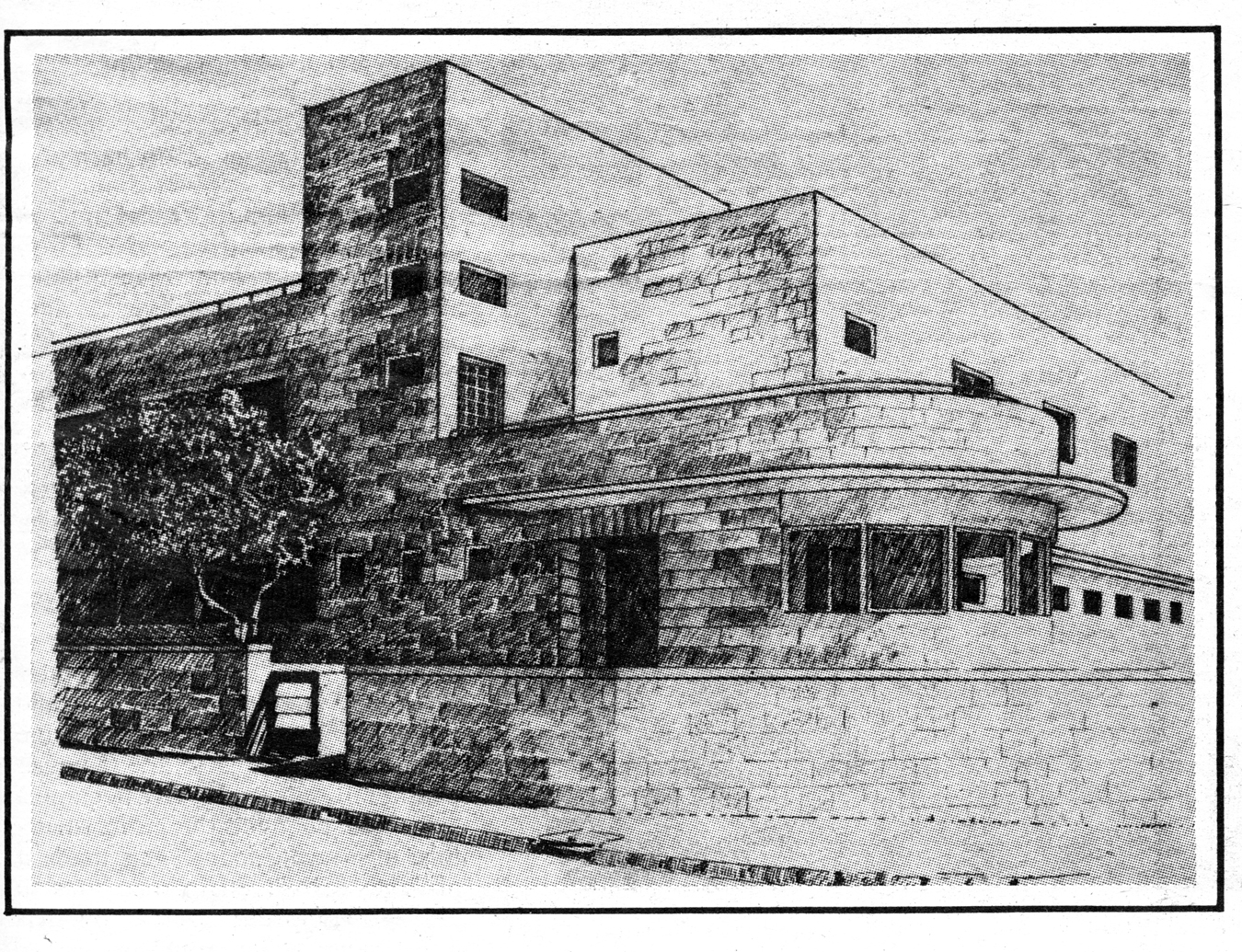

It was Kaufmann who introduced modern architecture to the country, with a near-Bauhaus style stressing function. Acutely sensitive to climate, he was the first to introduce concrete sun-shades projecting over windows facing the sun. At Degania, he built a double roof over a school so that the wind could circulate between the roofs and cool the classrooms. The potash works invited him to construct similar buildings for its workers at the Dead Sea. He built many villas for the wealthy, this work providing the bulk of his office’s income. Perhaps his most distinguished building is the one he built for the Egyptian Jewish banker Aghion in Jerusalem, which today serves as the prime minister’s residence.

THE FOUNDATION of the State of Israel was the fulfilment of his ideological aspirations but marked a downturn in his personal fortunes. He was not invited to take over the new government’s central planning positions and although deference was paid him as dean of the profession, large commissions were no longer offered to him.

“He was a bit stubborn and not flexible enough,” says a planner who knew him. “In 1948, for instance, when the villagers were evacuated from Ben Shemen to Kfar Vitkin, they wanted to expand one of the houses there for a dining hall. He refused because there was a possibility that a main road might eventually have to be built on that spot. He should have just given the people the amenities they needed and demolished the building afterwards, if it had to be. He couldn’t get past his halutziut.”

There is a universal touch of sadness in remarks made by friends and colleagues about Kaufmann’s last years. Writing a year after Kaufmann’s death, planner Ariel Kahane noted that Kaufmann’s ideas had become common property for younger planners and architects who did not realize their debt.

“This development led to disappointments during his last years. He was no longer offered the scope of work which would have been appropriate to his standing. He was ready to give his advice, but this was made use of only partially. His last years were darkened by this fact.”

Says someone who knew him closely: “He wasn’t getting work at the end and Avraham Hartzfeld [a Zionist leader] who was a great admirer of his, commissioned him to write about the history of planning in the country as a way of providing him an income. He died a poor man at a point where it could have been tragic if he had continued living.”

Apparently the only memorial to Kaufmann is a short street in Jerusalem’s Romema quarter called in his honour Rehov Ha’adrihal, The Architect’s Street.

Old-time Jerusalemites still recall him walking his bulldog in Rehavia — a handsome, courteous and pleasant man wearing a jacket with leather at the elbows and smoking a pipe. Sad as he may have been at the end, he could on those walks, reflect on a rare career.

“I don’t know of any place in the world,” he said in the 1930s, “that can offer as much satisfaction to an architect and planner as this country. Here we are beginning from the beginning.” The satisfaction Richard Kaufmann felt is still being shared by multitudes in the communities he shaped. 0