This photograph shows me waiting to enter the Jerusalem YMCA auditorium during the hearings by the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine on the partitioning of Palestine. At the time the territory was a British mandate and I was lecturing the British policeman, who was guarding the entrance to the auditorium, on Zionism. (It turned out that he was Irish and not particularly fond of the Brits.) In my hand is a pamphlet, titled “From Planning to Reality”, among other items. I wanted to be ready to bring examples of my father’s work to the attention of the UN commissioners should it be needed. This pamphlet was prepared by Keren Hayesod, which was sponsoring an exhibition of my father’s work at the Bezalel Art Museum (now Israel Museum) in honor of his 60th birthday (1947). The exhibit was of both my father’s plans for and aerial photos taken later of agricultural settlements supported by Keren Hayesod. These are but a few of the many settlements, garden suburbs, regional areas, residences and buildings he designed. The pamphlet describes the sponsorship activities of Keren Hayesod and the basic principals in planning and building that my father employed. To quote from the pamphlet:

“It is with the inception of the Keren Hayesod in 1920 that the main creative period in the architect’s life opens; and the fruits of that period are one hundred and two villages built in various parts of Eretz Israel, so that the face of the country today bears the imprint of his genius.”

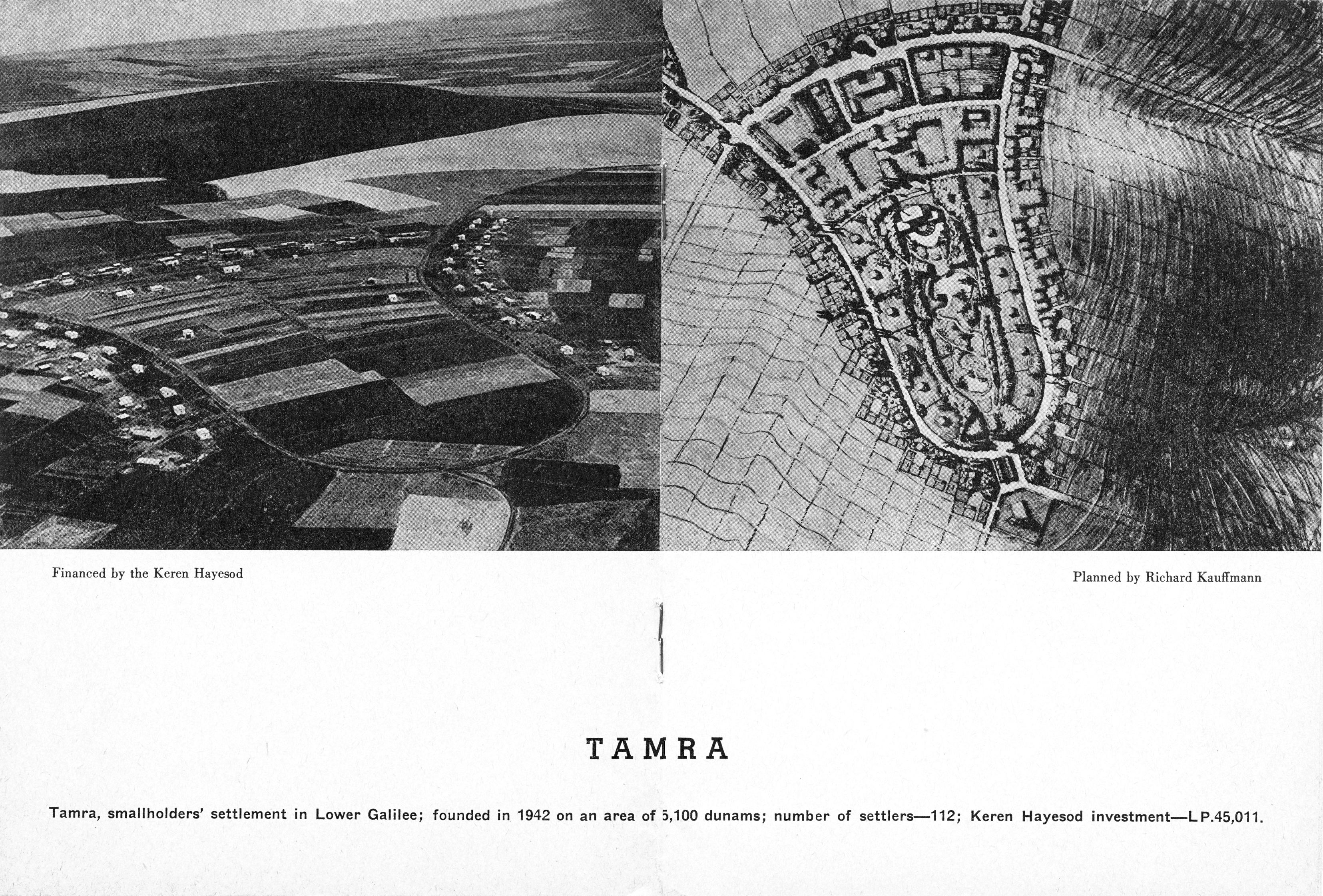

The “From Planning to Reality” pamphlet is 24 pages in length and was published in 1947 by the Jerusalem Press, Ltd. Each page has been photocopied and corrected to lighten the oxidized paper. Only two images are included in the pamphlet: 1) an aerial photo of the agricultural settlement Tamra, and 2) Richard Kauffmann’s rendering of the layout of the Tamra settlement plan. The title page and the images have been kept as photocopies. The main body of the text was converted using OCR to minimize file size. The text is divided into two parts: 1) An introduction expounding on the contributions of Keren Hayesod and its relationship with my father, and 2) A description of my father’s principles in planning and building that should be of interest to architects, town planners and historians everywhere.

E. K. F.

________________________________________________________________________

FROM PLANNING TO REALITY

ΤHE SIXTIETH BIRTHDAY of Richard Kauffmann, architect and town planner, is the occasion for the exhibition now arranged at the premises and under the auspices of the Bezalel Museum in Jerusalem, which is intended to present a review of the architect’s work, in particular his building and planning of towns and villages in Eretz Israel. This is a well-deserved tribute to a man of an originally artistic and constructive mind. At the same time, a review of Richard Kauffmann’s work necessarily involves constant reference to the Keren Hayesod, with whose progress and very existence the life-work of Richard Kauffmann is organically bound up. Without the Keren Hayesod, Kauffmann, the town-planner, would never have done the work for which he is famed. It is with the inception of the Keren Hayesod in 1920 that the main creative period in the architect’s life opens; and the fruits of that period are one hundred and two villages built in various parts of Eretz Israel, so that the face of the country today bears the imprint of his genius.

What associates Richard Kauffmann so closely with the Keren Hayesod?

The answer is simple. Only the advent of the Keren Hayesod soon after the First World War made realistic planning on the part of the Zionist Organization possible. Before that, the Zionist movement had barely progressed beyond the establishment of its ideological and political foundations. The formation of the Anglo-Palestine Company (as the Anglo-Palestine Bank—a daughter Company of Herzl’s Jewish Colonial Trust—was originally named), significant as it was, could hardly have been of more practical value than the banking facilities made available to a man with a small deposit and equally small credit. The beginning of activities by the Jewish National Fund in cooperation with the Palestine Land Development Company prompted the first experiments in agricultural settlement immediately before the First World War, from which experiments Merhavia, Kinnereth, and Deganiah were to emerge. But all this was insufficient to provide a working basis for the Palestine Office, which had been set up by the Zionist Organization in Jaffa-Tel Aviv to direct practical operations in Palestine, with Dr. Arthur Ruppin, a man of rare vision, at its head. Instead, the Palestine Office was only enabled to produce a crop of large-scale demands and unrealizable schemes and to form the conviction that all previous small-scale efforts were useless. It is true that even during the First World War Dr. Ruppin worked out plans for extensive agricultural settlement in the future which he submitted to the Zionist Inner Actions Committee through its President at that time, Professor Otto Warburg. Yet it was not until the Balfour Declaration had been made, Palestine occupied by Allenby’s army and Allied victory achieved, that the Zionist Organization really ceased to regard large-scale immigration and settlement in Palestine as a mere aspiration. Then also the conviction grew that neither at the beginning nor at any later stage could this undertaking be made dependent on outside help, whether in the form of international loans or of direct British support, but that the Jewish people itself must set up the central organ it had lacked until then to ensure the progress of its undertaking. Thus it was that at the Annual Zionist Conference of 1920 in London the central organ was created, under the title of The Eretz Israel (Palestine) Foundation Fund “Keren Hayesod.” Dr. Berthold Feiwel, one of Theodor Herzl’s early colleagues and a close associate of Chaim Weizmann, was appointed its first Managing Director.

The principal points in the programme of the Keren Hayesod for which the cooperation of the entire Jewish people was sought were immigration and agricultural settlement. The establishment of key industries and financial institutions (such as the Palestine Electric Corporation, the Palestine Potash Works, and the General Mortgage Bank), as well as the maintenance of the Hebrew school system and of social and medical services, also formed an integral part of the programme. But immigration and agricultural settlement were the first requirements. To open the gates of Eretz Israel to Zionists, to guide their steps and help them settle on the soil—that was, as it remains today, the point of undisputed priority.

A plan was devised which Congress after Congress revised and enlarged. It had one single aim—the building of the Jewish National Home in Eretz Israel; and a budget was drawn up for its realization. This Zionist budget did not conform to orthodox financial conceptions. A rational explanation alone could hardly do it justice. Political economists of the old school had considerable difficulty in understanding its working. As the late S. A. Van Vriesland, first Treasurer of the Zionist Executive in Jerusalem and a man with a deep understanding of the paradoxes of Jewish life, was wont to say, our constructive undertaking grew out of deficits. Indeed, the wholly inadequate means of the Keren Hayesod, insufficient in themselves to cover even small-scale projects, were miraculously multiplied and stretched out—by such means as short-term borrowing against anticipated future income—to a point where they managed to serve the needs of an extensive programme. On the strength of actual and potential income a “realistic” budget was drawn up within whose framework long-term planning was at long last possible. We refer to this as long-term planning, because theoretically it took seven years from the beginning to the completion of a settlement. And this is where Richard Kauffmann came in.

On the newly acquired land of the Jewish National Fund in the Emek Jezreel there now arose the new Jewish workers’ settlement; and to Richard Kauffmann fell the privilege of planning it. On him devolved the task of planning out every new village in detail and in the most practical way possible, having regard to social and cultural as well as to physical requirements. Soil structure, direction of wind and stream (if any), and distance from water springs—all had to be studied and taken into account; at the same time, communal amenities had to be thought off—a dining hall, which was also to serve as the meeting place for the whole settlement, infants’ and children’s houses, a room for study and recreation—as well as the ordinary farm buildings and dwelling houses. The planner had to study the typical requirements of the Moshav Ovdim, the Kvutzah or the Kibbutz, to minister to the needs of collective as well as cooperative living and farming, and, later on, of a third, intermediate form—the Moshav Shitafi. Richard Kauffmann, who had proved his ability to build attractively and comfortably for the middle-class town dweller, now had to build suitably and economically for the agricultural pioneer, with public funds provided by the Keren Hayesod. He carried out this task in an exemplary manner.

How planning and execution went hand in hand is illustrated by the present exhibition. Naturally, we can only see the bare plan and the picture of the actual village as it is seen from the air—in detachment. We cannot see the life of the people—the difficulties that had to be grappled with from the very beginning, the pains of birth, the sickness, the major and minor accidents, the tragedies which no settlement or family escaped. The camera has left out the small cemetery nearby where lie the early victims of disease and attack and the children that died in infancy. Nor do we catch the echo of happy sounds of festival and joy.

This is but a silent vision; the picture lacks its natural accompaniment of Hebrew song and the twittering of birds lured back to a land resettled and re-planted with trees.

And the spirit of the village, that organic being itself, is as elusive as the song of the people and of the birds.

But what does catch the eye is the outward form, the relationship between plan and reality.

With the help of Richard Kauffmann, the Keren Hayesod has tried to establish these physical forms for individual and collective modes of life. The attempt would never have been possible if it were not for Zionism and for the pioneering spirit that animated the settlers. Thanks to these factors there has been built up in the space of twenty-five years a structure that is no longer a faltering experiment but a successful beginning.

The present is one of the most difficult phases in Jewish history. More than two years have gone by since the end of the war which has taken of the Jewish people a toll of six million victims, and yet the right of the Jewish people to rehabilitation and to a life of its own is questioned. This exhibition, at all events, shows one characteristic aspect of how the Jewish people in Eretz Israel would answer the curse of the Galuth.

Leo Herrmann

RICHARD KAUFFMANN’S BASIC PRINCIPLES

IN PLANNING AND BUILDING

THE NAME of Richard Kauffmann as a Planner and Builder is inseparably linked with the upbuilding process in Eretz Israel. On his 60th birthday we look back with him on a record of achievement which includes houses and villages, suburbs and cities in his distinctive style to be met with everywhere in the country. From Dan in the north to Negba in the south, on the coastal plain and on the shores of the Dead Sea, in the communal settlements of the Emek and in its smallholder villages, his designs have become classics of Palestinian architecture. To mark the occasion and in tribute to Richard Kauff-mann, the present exhibition gives a review of what he has done in the past and plans to do in the future.

Thanks to the active cooperation of the Keren Hayesod, we have been able to assemble, not only many of Kauffmann’s plans, but also from the Keren Hayesod archives, a large number of aerial photographs taken by Zvi Kluger. Some of the other photographs are by Alfred Bernheim and Z. Bassan of Jerusalem, some by Hella Fernbach and Loewenheim of Haifa, and by Kalter of Tel Aviv. We are indebted to the Hebrew University for the loan of the large model by Yehuda Wolpert of the future aspect of the University-City on Mount Scopus.

The following is an attempt to give an outline of the main ideas underlying Kauffmann’s buildings and designs.

The Village

Here we enter uncharted territory. Town-planning and of late regional planning has become fairly common the world over but village planning on any large scale is known only in Palestine. When Kauffmann introduced it 27 years ago, it was a wholly new departure. Generally speaking, villages are the product of a lengthy historical process; they are made up of clusters of homesteads, either grouped round a church or marketplace, or strung along the banks of a river or a main road. Our old-new land posed a new problem. A fixed number of settlements had to be established, each under absolutely identical conditions, and to be erected within the shortest possible time. In this connection, Kauffmann concentrated on the three cooperative types of settlement, the smallholders’ village (Moshav Ovdim), the large communal settlement (Kibbutz), and, lately, the new intermediate type—the Meshek Shitufi. To plan them according to their individual requirements in the social and economic sense was his aim. Accordingly, each typical design has its special characteristics.

The Smallholders’ Village

Kauffmann started with Nahalal, a Smallholders’ Village, in 1921. In a settlement of this type, where every family has its own homestead, public and communal buildings should be so located as to be easily accessible to all. With this end in view the hillock is selected as the focus of the village. Following the contour line of the hillocks, Kauffmann constructed a road running round its upper part. The farmhouses are situated on the border of this oval. A second central ellipse girdles the grounds at the back of the farmhouses, and the whole is rounded off on the outside with a green belt. Inside the inner oval, with its Community Centre, School and administrative offices, Kauff-mann placed the dwelling houses of the teachers, artisans and clerks. This particular design so perfectly suited the landscape and the social structure of the settlement concerned that it became the pattern for the smallholders’ village up and down the country. Lately, Kauffmann has used a similar design for Beth Joseph in the Beisan Valley, but there, for reasons of security, the style is somewhat more rigid.

The Communal Settlement

At the same time Kauffmann turned his attention to the Kibbutz and the Kvutzah. These two dominant types of settlement are based on the strict principle of communal life and property. Their layout, therefore, differs fundamentally from that of the Smallholders’ Village. According to Kauffmann, the essential thing is to keep the various zones apart and still preserve the unity of the whole. Consequently, Kauffmann separates the residential zone of the grown-ups, with their dining-hall and communal centre, from that of the children with their school, also the workshops and storerooms, and both from the respective zones allotted for the poultry runs and the cow-sheds. Wherever feasible, a narrow green belt marks off the different zones. One of the main problems confronting architects in Palestine is the climate. Kauffmann tackles it by opening his houses to the north-west to give access to the prevailing breeze. The farm buildings, on the other hand, are sited towards the east, so that the wind should not blow from them to the living quarters. Incoming and outgoing traffic is kept separate from internal traffic.

From the very outset Kauffmann recognised the danger of the rigidly uniform design. In every single case, therefore, he sought to do justice to the distinctive features of the landscape and of the settlement concerned.

In 1921 Kauffmann started with the layout of Kvutzath Geva, following it up shortly afterwards with the twin settlements of Ein Harod and Tel Yosef. In his original plan these two settlements located on the slopes of a hill in the Eastern Emek Yez-reel, were so disposed that their major axes met at the top of the hill, where communal buildings for the entire neighbourhood were to be erected. This plan did not materialise. Nevertheless, the converging lines of the two settlements are still plainly visible today.

Among the other numerous Kibbutzim planned by Kauffmann let us mention the outstanding layout of Maoz in the Beisan Valley, with its dining-hall situated in the centre of the settlement. In nearby Kfar Ruppin, one of the two hillocks is utilised for the cultural centre, the other for the school, which gives the settlement its distinctive appearance. In Dan, Kauffmann has been able to carry out his demarcation of the various zones to the full. There the workshops separate the cowsheds from the poultry-runs, whilst the lawns and gardens between the dwelling houses, also in a separate zone, are orientated towards the Hermon. This is more than a purely aesthetic consideration: the view is bound to have a profound effect on those who work and live in sight of this impressive mountain range.

The Meshek Shitufi

The many personal problems arising out of group life have lately given rise to this newest form of cooperative settlement. Here, too, Kauffmann blazed a new trail. The individual dwelling houses have to be organically related to the communal buildings. In Moledeth, established in 1937, Kauffmann therefore again takes advantage of the raised ground in the centre to place on it the public garden, the school and the community centre, thus making the public amenities easily accessible from all parts of the village.

Town and Regional Planning

This is a less thankful task than the layout of cooperative settlements, because in the latter the land is a fixed factor made available by the settlers and/or the national institutions. In towns it is a variable factor, depending sometimes on the stiffness of the public bureaucracy, always on the fluctuations of private speculation in land, with the result that when the architect plans for a town, he knows that only part of his ideas is realisable. For these reasons Kauffmann has always battled for a better order of things. Some of the plans exhibited here should be looked at in this light. We know how many unique opportunities were irretrievably lost in the planning of our large towns. Some of Kauffmann’s plans show what might have been done. Today everyone is aware of the overcrowded state of Haifa, of the bad communications between the town and its port—the most important on the western seaboard of the Near East. Kauffmann’s plans show that only a short 20 years ago the expansion of the town could have been directed towards the Kishon Plain across the artificial barrier of the Carmel shoulder. Had that been done, Haifa would have had for its centre the plain to which cooling breezes have free access. At that time already Kauffmann conceived the idea of shifting the railway line and constructing a by-pass by means of a tunnel through the Carmel range, leading approximately from Khayat Beach in a north-easterly direction; that would have directed traffic, including the railway line and would eventually have formed part of the land route from London to Cape Town, bye-passing the town.

No less instructive is Kauffmann’s plan for a part of Tel Aviv stretching from Allenby Road to the present Gordon Street. In a seaside town attention should have been focused on vistas opening westwards to the seas. The first line of dunes immediately behind the beach should have been reserved for bathing and recreation, and the whole part shut off from all traffic by means of a wide green belt. The design further illustrates the folly of having leveled the low dunes instead of placing on their ridges public buildings to serve as gravity centres for certain selected groups of buildings. It is regrettable that Kauffmann’s many valuable suggestions should have been ignored.

Affuleh in the Emek Yezreel is still one of the dreams which have not come true. The idea that gave birth to it was that the growing density of population in that region would call for a country town as its natural centre. Situated just on the watershed between the Mediterranean and the Jordan basin, it was to be of circular shape, strung on the Haifa-Damascus railway line which was to pass through a cutting below the level of the town. One day this dream, too, may find fulfillment.

One of the plans executed in their entirety is that of the garden suburb of Beth Hakerem near Jerusalem. It was designed to harmonize with the natural rock terraces, and with the Teachers Training College crowning the central elevation. The park is laid in a depression where the soil is deepest. The present main road is to be diverted as a bye-pass-road west of the school.

Style.

Kauffmann holds that architectural style is determined by three factors — the spirit of the age, the latest technical facilities available, and local conditions. At the same time, the overriding principle of modern architecture remains that, from the bottom upwards, every part of a structure should be dominated by the purpose which the whole is to serve — whether domestic, industrial or agricultural. This is today a universally recognized principle, so that we shall deal merely with a few special applications of it to local conditions for which Kauffmann is responsible.

One of the main problems of architectural design in Palestine is the climate with its high summer temperatures and its heavy winter rainfall occurring in a relatively short period. This implies considerable use of insulating devices — above all, Kauffmann maintains, for the roof; for in summer the sun’s rays fall almost vertically at midday, heating the roof more strongly than the walls. On the other hand, adequate protection against the rain calls for a very expensive asphalt covering. Cork, pumice-stone and gas concrete as insulating material are also costly. Thus, when building the school at Deganiah in the hot Jordan Valley, Kauffmann hit upon the idea of mounting a Ternolith roof on a light wooden structure two metres above the ceiling proper, so as to allow the wind to circulate freely between the two roofs and exercise a cooling effect on the schoolrooms. The idea proved a success. The classrooms remained relatively cool. The Manager of The Palestine Potash Works who saw the buildings in Deganiah, promptly invited Kauffmann to construct similar buildings at the Dead Sea.

On private houses as, for instance, those built for Pomeranz and Goitein, Kauffmann makes use of other protective devices. Here the special qualities of reinforced concrete allow him to mount projecting canopies over the windows; as a result the latter remain shaded in summer and protected from the downpouring rain, while still admitting sufficient sunshine in winter.

This example of the use of concrete leads us to consider the combination of concrete and stone which occurs so frequently in Jerusalem. Kauffmann regards it as important that the identity of each of the materials used should be preserved and never masked.

A striking example of the functional conception referred to above is the “Hamkasher” Garage in Jerusalem. Its isometric perspective shows the intention of adding a second floor later on. The ground floor will then house the workshops, the upper floor the motor-buses, for which arrival and departure ramps are to be constructed. Since the lower part of the building will be subjected to pressure, Kauffmann has inserted reinforced concrete frames, which are not only recognizable in their functional capacity but also determine the rhythm of the frontage — a technical device turned to aesthetic advantage.

Similar modern devices have enabled Kauffmann, jointly with Engineer Rappaport of Tel Aviv, to refashion the Arab villa Abouljiben, south of Beth Dajan on the Tel-Aviv-Jerusalem Road. An excessively long hall was shortened and so adapted for living purposes and thrown open to the magnificent view towards the west and the north. The verandah, a mixture of conflicting styles, was relieved of its Romanic columns and Gothic arches and thus made a frame for the surrounding landscape. The gentle incline in the garden was utilised for cascades the waters of which are collected in a basin with a fountain.

A typical example of Kauffmann’s recent work is the Aghion House, built in the traditional Mediterranean style round an inner court, with a basin in the centre. Even the flowers to be planted around that basin were provided for in the original plan.

Perhaps the most fitting characterization of Kauffmann’s work would be in the words of the late J.L. Motzkin, spoken of Ussishkin on his 75th birthday at one of the Zionist Congresses: “If anyone wants to visit Ussishkin in his house in Rehavia, he needs no guide. All he has to do is to walk along the main street until he suddenly comes on a house which seems cast in iron. That is the man, firmly based like a rock.” That, too, is part of the function of the architect — to make the house represent the character of its occupant.

Kauffmann has already covered a long way in Palestine. But, like every creative artist, he has only got to the middle of the way.

F. Schiff

LIST OF SETTLEMENTS BUILT ACCORDING TO PLANS

BY RICHARD KAUFFMANN WITH THE HELP OF THE

KEREN HAYESOD

a) Settlements figuring in the exhibition.

Name and FormOf Settlement |

YearEstablished |

PopulationEnd 1946 |

Area inDunams |

Keren HayesodInvestmentUp to 1946 |

Avuka, Comm. S. |

1941 |

108 |

1,330 |

25,015 |

Eilon, Comm. S. |

1938 |

333 |

3,900 |

28,950 |

Beeroth Yitzhak, Comm. S. |

1943 |

224 |

6,000 |

56,909 |

Beth Alpha, Comm. S. |

1922 |

518 |

6,000 |

55,009 |

Beth Yosef, Smallh. S. |

1937 |

197 |

3,670 |

48,276 |

Geva, Comm. S. |

1921 |

386 |

3,035 |

22,970 |

Givatayim, Wrks. S. |

1922 |

7,000 |

1,866 |

|

Gvath, Comm. S. |

1926 |

674 |

5,535 |

20,162 |

Ginegar, Comm. S. |

1922 |

401 |

2,550 |

17,286 |

Deganya A, Comm. S. |

1909 |

371 |

1,720 |

14,995 |

Dan, Comm. S. |

1939 |

324 |

1,692 |

26,736 |

Dane, Comm. S. |

1939 |

562 |

3,200 |

20,479 |

Hazorea, Comm. S. |

1936 |

406 |

2,990 |

7,224 |

Hasharon (Ramath David), Comm. S. |

1926 |

329 |

3,734 |

20,142 |

Haifa, Town |

70,000 |

|||

Hanita, Comm. S. |

1938 |

222 |

3,550 |

32,293 |

Hafetz Hayim, Comm. S. |

1944 |

170 |

1,210 |

29,805 |

Yagur, Comm. S. |

1922 |

1,388 |

5,000 |

44,872 |

Kinnereth (Kvutzah), Comm. S. |

1908 |

553 |

2,600 |

27,865 |

Kfar Hahoresh, Comm. S. |

1933 |

236 |

800 |

25,221 |

Kfar Vitkin, Smallh. S. |

1933 |

915 |

3,777 |

56,545 |

Kfar Hassidim, Smallh. S. 1924 |

1,450 |

9,400 |

78,316 |

Kfar Yehoshua, Smallh. S. 1927 |

584 |

10,132 |

40,223 |

Kfar Ruppin, Comm. S. 1938 |

216 |

4,075 |

24,622 |

Moledeth, Coop. Sm. S. 1937 |

206 |

8,630 |

19,558 |

Maoz Hayim, Comm. S. 1937 |

465 |

4,592 |

33,664 |

Maale Hahamisha, Comm. S. 1938 |

235 |

720 |

21,117 |

Matzuva, Comm. S. 1940 |

*118 |

1,500 |

29,803 |

Mishmar Haemek, Comm. S. 1926 |

458 |

5,300 |

26,606 |

Negbah, Comm. S. 1939 |

325 |

2,724 |

23,676 |

Nahalal, Smallh. S. 1921 |

847 |

8,846 |

81,233 |

Neve Eitan, Comm. S. 1938 |

209 |

2,693 |

21,658 |

Ein Hamifratz, Comm. S. 1938 |

347 |

1,135 |

18,360 |

EM Harod, Comm. S. 1921 |

1,120 |

14,078 |

119,150 |

Ayanoth (School), Tr. F. 1930 |

390 |

350 |

|

Amir, Comm. S. 1939 |

271 |

2,510 |

27,057 |

Afule, Urb. S. 1925 |

2,600 |

18,277 |

|

Ein Zeitim, Comm. S. 1946 |

87 |

2,200 |

12,598 |

Shkhunath Ono, Wrkrs. S. 1939 |

310 |

100 |

|

Tel Yosef, Comm. S. 1921 |

893 |

12,160 |

102,397 |

Tamra, Smallh. S. 1942 |

112 |

5,100 |

45,011 |

Valley of Hefer |

6,500 |

50,000 |

600,000 |

(approx.) |

Abbreviations: Smallh. S. = Smallholders’ Settlement of the Jewish Workers’ Federation; Comm. S. = Communal Settlement; Coop. Sm. S. = Cooperative Smallholders’ Settlement; Wrks. S. = Workers’ (Suburban) Settlement; Urb. S. = Urban Settlement; Tr. Farm = Training Farm; Mizr. Wrks. Mizrahi Workers’ Settlement.

b) Settlements not represented by plans or photographs.

Name and FormOf Settlement |

YearEstablished |

PopulationEnd 1946 |

Area inDunams |

Keren HayesodInvestmentUp to 1946 |

Avihayil, Smallh. S. |

1932 |

497 |

1,882 |

23,176 |

Usha, Comm. S. |

1937 |

235 |

1,470 |

17,877 |

Elyashiv, Yemen. S. |

1933 |

350 |

979 |

12,424 |

Beer Touvya, Smallh. S. |

1930 |

719 |

4,575 |

|

Beth Hillel, Smallh. S. |

1940 |

98 |

1,085 |

46,018 |

Beth Hanan, Smallh. S. |

1930 |

422 |

1,748 |

23,673 |

Beth Yehoshua, Comm. S. |

1938 |

133 |

1,275 |

35,188 |

Beth Yanai, Smallh. S. |

1933 |

80 |

2,300 |

|

Beth Oved, Smallh. S. |

1933 |

189 |

660 |

300 |

Beth Shearim, Smallh. S. |

1936 |

340 |

2,900 |

12,828 |

Givoth Zeid, Comm. S. |

1943 |

138 |

2,300 |

20,518 |

Givath Hashlosha, Comm. S. |

1925 |

768 |

1,404 |

45,437 |

Givath Hayim, Comm. S. |

1932 |

692 |

1,282 |

58,049 |

Gezer, Comm. S. |

1945 |

130 |

4,018 |

45,942 |

Gan Shlomo(Shiller), Comm. S. |

1927 |

238 |

646 |

5,785 |

Hertzliya, Village |

1924 |

5,400 |

9,257 |

|

HuIda, Comm. S. |

1930 |

289 |

3,531 |

30,086 |

Heruth, Smallh. S. |

1930 |

390 |

2,000 |

59,925 |

Yavne, Comm. S. |

1941 |

316 |

3,441 |

24,188 |

Yedidya, Smallh. S. |

1935 |

285 |

1,075 |

22,877 |

Kfar Uriya, Smallh. S. |

1944 |

182 |

4,240 |

36,175 |

Kfar Azar, Smallh. S. |

1932 |

332 |

892 |

16,090 |

Kfar Ata, Suburb. S. |

1925 |

2,200 |

3,600 |

|

Kfar Bilu, Smallh. S. |

1932 |

205 |

644 |

|

Kfar Barukh, Smallh. S. |

1926 |

260 |

6,665 |

33,164 |

Kfar Brandeis, Smallh. S. |

1928 |

170 |

560 |

|

Kfar Gideon, Smallh. S. |

1923 |

90 |

3,600 |

26,707 |

Kfar Hamaccabi, Comm. S. |

1936 |

235 |

1,650 |

8,929 |

Kfar Hess, Smallh. S. |

1933 |

350 |

1,892 |

18,877 |

Kfar Hittim, Coop. Sm. S. |

1936 |

246 |

3,677 |

39,495 |

Kfar Hayim, Smallh. S. |

1933 |

347 |

1,597 |

32,157 |

Kfar Yehezkel, Smallh. S. |

1921 |

478 |

6,000 |

66,093 |

Kfar Menahem, Comm. S. |

1937 |

324 |

4,771 |

28,116 |

Kfar Netter, Smallh. S. |

1939 |

163 |

1,440 |

37,058 |

Kfar Szold, Comm. S. |

1942 |

327 |

2,135 |

48,121 |

Mizra, Comm. S. |

1923 |

415 |

4,200 |

26,276 |

Massada, Comm. S. |

1937 |

271 |

1,443 |

6,683 |

Mesiloth, Comm. S. |

1938 |

381 |

2,895 |

21,710 |

Mishmar Hasharon, Comm. S. |

1933 |

368 |

619 |

36,562 |

Mishmaroth, Comm. S. |

1933 |

237 |

1,274 |

30,088 |

Neve Yaakov, Suburb. S. |

1924 |

140 |

489 |

|

Nitzanim, Comm. S. |

1943 |

140 |

1,600 |

42,986 |

Ein Hanatziv, Comm. S. |

1946 |

158 |

2,100 |

8,531 |

Ein Haemek, Smallh. S. |

1944 |

167 |

2,000 |

70,364 |

Ayanoth (Ramath David), Comm. S. |

1926 |

256 |

3,750 |

19,949 |

Zur Moshe, Smallh. S. |

1937 |

200 |

1,280 |

38,941 |

Kiryath Hayim, Wrks. S. |

1933 |

7,500 |

3,300 |

|

Kiryath Haroshet, Suburb. S. |

1935 |

230 |

||

Kiryath Anavim, Comm. S. |

1920 |

352 |

582 |

30,739 |

Ramath Gan, Urb. S. |

1921 |

12,500 |

2,436 |

|

Ramatayim, Village |

1925 |

1,350 |

2 230 |

|

Shear Yashuv, Smallh. S. |

1940 |

126 |

1,735 |

43,577 |

Sdeh Yaakov, Mizr. S. |

1927 |

480 |

6,170 |

21,567 |

Sde Nehemya, Comm. S. |

1940 |

185 |

1,320 |

13,628 |

Shaar Hagolan, Comm. S. |

1937 |

408 |

1,340 |

6,659 |

Sharona, Smallh. S. |

1938 |

109 |

6,432 |

41,583 |

Sand, Comm. S. |

1926 |

457 |

4,453 |

20,084 |

Tel Yitzhak, Comm. S. |

1938 |

208 |

1,275 |

31,025 |

Tel Litvinsky, Suburb. S. |

1934 |

150 |

1,614 |

|

Tel Mond, Village |

1929 |

550 |

3,642 |

|

Tel Adashim, Smallh. S. |

1923 |

315 |

7,490 |

50,801 |

* Additional financial contributions on the part of subsidiary companies of the Keren Hayesod are not listed.

_________________________________________________________________________