by Richard Kauffmann

Member, Town Planning Institute

EILAT is on everyone’s mind and on everyone’s tongue today. The very word opens up hopes of a splendid future of cultural and commercial relations with Asia, Africa and Australia. But what decisive structure are we imparting to this focal point of such broad perspectives? Let us consider what must be done about an opportunity that will never present itself again.

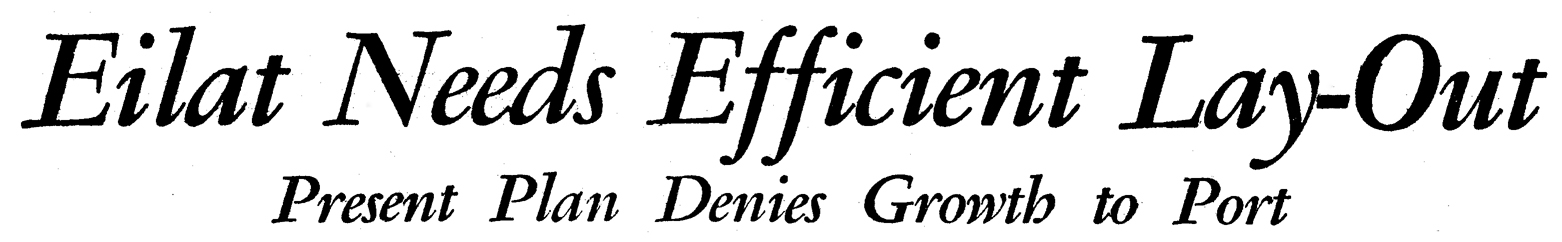

A model of the proposed Eilat town plan, prepared by the Town Planning Department of the Ministry of Interior, was exhibited recently at the new Histadrut building in Jerusalem. A photograph of this model, together with a descriptive article entitled “Planning a Red Sea Town” by Arieh Ephrat, appeared in The Jerusalem Post on April 15.

When I saw the model for the first time, I was dismayed at the lack of correlation between the projected harbour proper and what should normally have been its “hinterland” — the projected communications, warehouse, commercial and industrial zone. In the projected layout of the town, its main working centres have been pulled apart, the lonely harbour at one end and the commercial and industrial zones at the other. The harbour is to be built at the narrowest point of the coastal strip, just where the hills drop steeply into the sea.

From a technical point of view, this makes it easier to build the harbour, since the deep sea is not far offshore. But a harbour is not an object in itself: it can only be efficient if it is organically integrated with the working town ft needs a hinterland of warehouse, commercial and industrial zones with room for all possible extensions, the extent of which can hardly be foreseen today, and for proper communications by rail, road and possibly inland canals also, as well as helicopter and regular air services that are functionally related with it.

When I voiced this opinion to the head of the Planning Department, who had taken me to the exhibition, he told me that the place for the harbour had been fixed by the Ministry of Development; and Mr. Ephrath’s article states that no fewer than three Ministries — Interior, Development and Labour, had a say in the plan. Where is the coordinating Ministry of Planning that was proposed by Professor Sir Patrick Abercrombie in his report on a National Plan for Israel, and independently by this writer in The Jerusalem Post of December I, 1952?

According to the present Plan, the residential town of Eilat will be laid out on the “gentle slope” to the north of the harbour. Here, in addition to the fact that the areas near the shore should definitely be reserved for the harbour and the warehouse industrial and commercial areas, there is a consideration of climate which is of definite importance.

Housing Area

Eilat’s extreme summer heat is very trying, and it reduces the residents’ working capacity as well as their well-being considerably. The new “coolers” to be installed in Eilat’s houses are merely a costly palliative. Yet the town has been blessed with a hillside rising some 800 metres to an extended plateau, where cool breezes and lower temperatures would make it possible for the residents to recuperate during their hours of rest, recreation and sleep if the town’s residential quarters were built there, along with the schools, a hospital, etc. The relatively small housing quarter of today could be conceived as a downtown residential area that would not be further expanded. This measure is bound also to free valuable space for the future working town,

I beg not to be misunderstood. The last thing I want to do would be to detract from the planners’ interests or their achievements, but it seems to me that the whole layout of the port and the town should be reconsidered on the basis of an imaginative plan directly connecting the harbour to be constructed at the head of the Gulf with its commercial and industrial section in the fiat parts near the seashore (where evaporating pans and palm-tree avenues are now envisaged) and providing for the main residential areas on the high plateau to the west.

In Haifa, where the climate is far milder, an increasing proportion of the population seeks to live on the Carmel, now connected with the lower parts of the city with three roads, one of which climbs from Nesher to an altitude of 550 metres at the summit of the Carmel. A similar arrangement is imperative for Eilat, where a road and a funiculaire to the uphill quarters should be planned,

The analogy with Haifa applies in yet another respect. When the British planned a harbour for Haifa about 1925, this writer opposed the project and suggested one of his own on the ground that the Mandatory scheme, planned by Palmer, Tritton and Randall, harbour engineers, only took technical considerations into account and did nothing to provide a proper ‘hinterland” for the harbour or to solve the issue of the simultaneous development of the city with its port.

The writer therefore proposed to locate the harbour in the south-east corner of the Bay and to develop part of it as an inland port around the Kishon — after canalization. The wide Kishon plain was the most suitable location for a business and industrial area, and for a working town that would thus be intimately connected with its port and at the same time avoid the numerous bottlenecks that have since developed in Haifa in this respect.

This advice was not heeded, and the difficulties in which the location of its harbour have involved Haifa since then are all too well known, resulting in an incalculable drain on our national income, the end of which is not yet in sight despite the fact that a new harbour is at last arising on the Kishon, at the spot proposed by the writer over 30 years ago.

We must not make the same error at Eilat. What was a mistake in Haifa may prove irreparable there.

In 1925 the Jewish Agency leadership, under the guidance of Arlosoroff, were in favour of the Kishon solution, but the last word rested with the British.

Today the last word is with us.

________________________________________________________________________

(Editor’s note: This is an OCR version of an article published June 14, 1957 in the Jerusalem Post). The drawing in the article is not representative of Richard Kauffmann’s work and was likely drawn by a Jerusalem Post staff person.