Editor’s note: Images of article were obtained courtesy of the Central Zionist Archives, Jerusalem. The original article was published in the Jerusalem Post on December 1,1952

The “foreign expert” mentioned below is likely Professor Sir Patrick Abercrombie, a distinguished town planner in England and a member of the Town Planning Institute.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

FOR Rosh Hashanah 5713 the Government of Israel presented us with a comprehensive survey of the plans for the physical development of the country, as designed by Mr. Arieh Sharon and his many collaborators. With its numerous coloured plans and photos of villages, settlements, towns and typical landscapes, the volume is admirably well produced by the Government Printing Press and Survey of Israel Press; an English summary of the Hebrew text does credit to the Kfar Monash Printing Press, and the whole is a fine example of local craftsmanship.

Above all, this volume gives an insight into the magnitude of the task whose significance for the overall physical shaping of the whole country cannot be overestimated.

A first glance shows what good work has already been done with much fervour, and the general outline of some of the towns and especially the lay-out of some of the neighbourhood units reveals a satisfactory general trend. On further examination, however, a number of questions arise. A few only of these questions, selected at random, can be discussed here.

The National Master-Plan

Where is the general utilization plan of the country? Any national master-plan must obviously be based on such a plan, which is itself designed on the basis of a national map showing the quality of soil, arid areas, water and natural resources, historical sites, beauty spots, etc. This principle has been generally accepted since Dr. Dudley Stamp, the English pioneer in this field, insisted on it in his works. It must be asked whether a plan of this kind has been prepared for the whole of the country as the indispensable basis of the master-plan.

Between pages 26 and 27 a large folding plan is reproduced, called the national master-plan. This plan itself, as well as the various townplanning schemes, are based, in general, on recent planning methods adopted in Europe and the United States. A national master-plan should form the basis of the entire physical planning of the country. By properly incorporating and correlating the various essential components of physical development, existing as well as proposed, such as communications, urban and rural areas, afforestation, parks and green belts, etc., it should fulfil its function as the key to the whole development, and not least to all regional and detailed planning.

One of the most important components is a national irrigation scheme, This scheme is not found in the master-plan although it should be one of the main attributes of the plan decisively influencing its preparation through proper correlation of the irrigation system with the system of communications, zoning, etc.

National parks and afforestation areas should form an organic entity, allowing for interconnection of larger regions and afforestation areas by a network of green belts. Instead of providing for a continuous and uninterrupted green system, parks and green belts are scattered over the whole land without organic connections which would enable youth groups, hikers and tourists to move from reservation to reservation by foot.

This approach is all the more regrettable because the country offers unique opportunities for appropriate planning. Nature itself has connected the hill areas of the east and north by means of wadis, gorges and rivulets to the coastal belt with its ranges of low “kurkar” (sandstone) hills and sand dunes. Here is the natural key for a proper arrangement of a national green system. At the suggestion of the present writer, even the Mandatory Town Planning authorities had long ago made legal provision for a rudimentary coastal green belt. It would be a pity if our authorities, instead of enlarging it, allowed it to be dropped altogether.

Safeguards for Precious Soil

Our land is relatively poor in good agricultural soil. Only approximately 7,500,000 dunam of a total area of 20,800,000 dunam or approximately one third may be considered as agricultural soil suitable for cultivation. The intention of redeeming large areas of wasteland and neglected soil has already resulted in considerable outlay and human effort. Accordingly, one of the most important guiding principles in determining the location of new towns and settlements must obviously be that not a single dunam of good soil shall be used for other than agricultural purposes, unless absolutely necessary. Here again a proper land utilization map should guide our efforts.

In fact, however, new towns and settlements have been earmarked in the plans on first-class agricultural soil instead of pushing them to nearby arid areas. This would not be detrimental to their general location, but would save hundreds of thousands of dunams of good soil for agricultural use. In travelling through Israel today one cannot help noticing with regret how new town enlargements and housing schemes are springing up on excellent soil, whereas sand dunes or stony areas in the vicinity are lying idle, as, for instance, in Rishon le-Zion and Hadere. It may be mentioned in passing that building on sandy or stony ground is much healthier and cheaper than on deep or heavy soil.

The Haifa Region

Space permits only one or two more observations. It is to be regretted that a proper master-plan for Haifa and its region is lacking. As this is unfortunately the case, new developments for the harbour in the Kishon estuaries have recently overtaken the sound development of what is perhaps our most important town to the decisive detriment of all factors involved, foremost among them the harbour and the town itself.

This omission is all the more surprising because Mr. Sharon himself describes the future Haifa as a “centre of international trade and industry” which “may in future play an important part in international communications.” In the light of these statements, which-can be wholeheartedly endorsed, the plan shown on page 63 does not seem to meet the case, either in its arrangement of the harbour and the adjoining areas, or in other features, as for instance the intercontinental railway communications which cut through the whole area of town and harbour instead of being led around in a south and easterly direction as a bypass railway, tunnelling Mount Carmel.

For further study of this important Issue, the reviewer must refer to his article “The First Planning of the Haifa-Acre Region in 1925-26 and the Problems of Today“. publ. by Massadah, Tel Aviv.

Tel Aviv’s Railway

A similar drawback is revealed in the proposed new South-North railway line which cuts right through the whole length of Tel Aviv, splitting the town into two parts. It runs along the Wadi Musrara, where a narrow green belt has been proposed along the wadi bed, the only green and recreation area in the heart of the town worth mentioning the purpose of which will certainly be defeated when the main railway passes through its whole length.

Moreover, it does not seem reasonable for a railroad to be built precisely along this lowest part of the town, where a constant danger of flooding exists even if costly drainage work were undertaken.

The right location of the main railway-line would again be a bypass in the East, with only feeder branches for local use.

In the Master-Plan for Jerusalem, a suitable alternate site for the Hebrew University and Hadassah, omitted in the plan, would have been of decisive importance.

Rural Planning

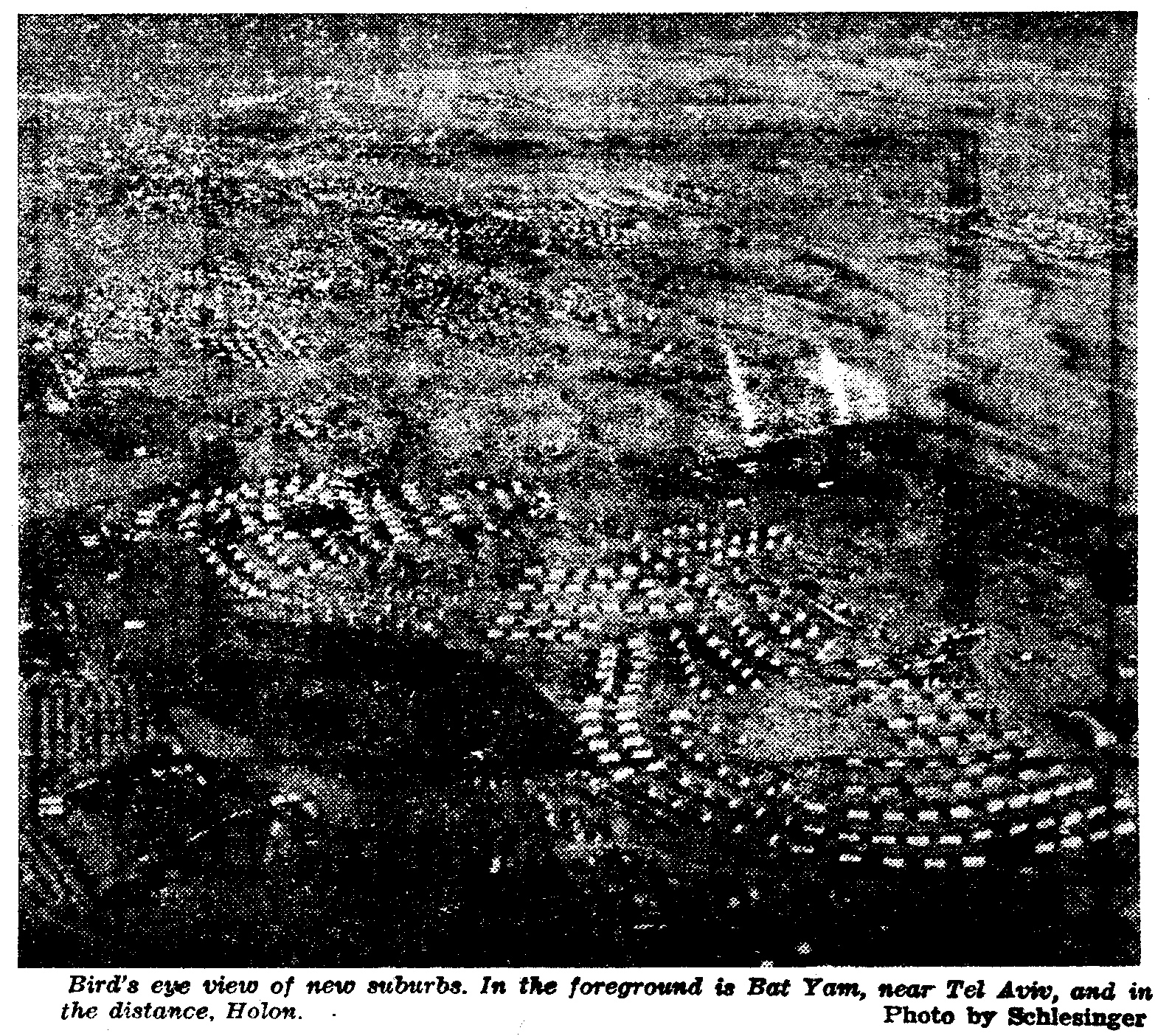

Several examples of rural planning are reproduced in the book, in air-photos as well as in typical plans of villages. Much pioneering work has been done in this field in the land of Israel, where systematic planning of agricultural settlements was undertaken for the first time more than thirty years ago and has become an internationally acknowledged model.

The reader will be under the impression that this planning too was the work of the Government Planning Department. By accepted standards of international usage it would have been incumbent upon the author not merely to cite the photographers, but in the first place the names of the authors of these plans, for instance:

Kibbutz Ein-Hashofet (page 29) by the late Norman Lindheim; Moshav Ovdim Nahalal (page 30), Moshav Shitufi Hissin (page 31), Kibbutzim Ain Harod and Tel-Joseph (page 32) by Richard Kauffmann. On plate XVII there is an air photo of Haroshet Ha-Goyim which was designed by Professor Alex Klein.

Wanted: A Town and Country

Planning Act

Even the most careful planning is doomed to failure if adequate legislation is lacking. Such legislation should at least accompany the planning activities, but it would be even preferable had it been enacted beforehand. If no such legislation is mentioned in the book, for the good reason that there is no proper law in existence. More than anyone else, the Government’s Planning Department itself must be aware of all the handicaps and drawbacks resulting from this deficiency, but the public, too, suffers from the resulting stagnation in development.

One of the first acts of the Mandatory Government was a Town Planning Ordinance, promulgated as long ago as in 1921. Based on the then prevailing policy and on piece-meal-planning, this Ordinance was revised several times. Yet, together with some others of the Mandatory period, it has remained the legal basis of all planning. In several other countries legislation was already enacted before the first World War, and in England the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947 provided the necessary instrument for modern development. Here unfortunately, we still labour under an obsolete legislation which was never meant for regional, much less for national country planning.

Status of Planning Department

Another question bearing on the success of planning is the status of the Planning Authority itself. This Department has already been transferred three times. Originally attached to the office of the Prime Minister, it was subsequently shifted to the Ministry of Labour, and landed recently in the Ministry of the Interior. In addition, Planning Departments exist in other Ministries, as for instance, in the Ministries of Communications and of Commerce and Industry.

It is perhaps no wonder that, as experience has shown, the planning authorities are not endowed in their present set-up with sufficient powers, nor are they adequately represented in the Cabinet, the Knesset, and in Public Relations. In view of the vital importance of the task for the whole future of the country, a separate Ministry of Town and Country Planning would seem to offer the only effective solution. Even in Britain, where large-scale planning is, so far, confined to regional schemes, a special Ministry of Town and Country Planning was established long ago.

Collaboration and Coordination

“Effective planning calls for collaboration and coordination,” with this apposite statement the book is introduced to the reader; but when it goes on to say that “during the past two years the activities of the Planning Department have been based on such collaboration,” one feels inclined to voice serious doubt, not about the collaboration within the department itself, on which the outsider has no information, but in a much wider sense.

It is, or should be, imperative that with this unique opportunity of shaping the physical outlay and appearance of the country, all those who are qualified to make useful contributions should be given the opportunity for collaboration. This has unfortunately not been done. On the contrary, local specialists with many years of professional experience in the field of planning, abroad as well as here, have neither been consulted nor otherwise encouraged to collaborate.

The departmental monopoly thus created is, no doubt, responsible for many of the failures, a few of which have been mentioned. In other countries, such as Britain, which has made outstanding contributions to the science and practice of planning, the “Town Planning Consultant” has become an indispensable part of the system.

It may be useful to invite foreign experts for the elucidation of special problems, but this can be no substitute for constant collaboration and consultation with local specialists whose thorough acquaintance with the problems involved and practical experience makes it imperative to seek their advice and collaboration.

The few observations which could be offered in this review, are intended as constructive criticism only. It is not yet too late to reconsider both the organization and the proposals of the planning authorities. Unless this is done, we shall have to admit that there is a good deal of truth in the apprehensions of a foreign expert who, after his departure front Israel, wrote to the present reviewer;

When the responsible authorities are anxious to spend money in a wrong way, and when they fear criticism of their dilettantism, I can’t help it. Here (i.e. in the writer’s country) you are obliged to submit your opinions to the highest authorities and criticism is appreciated. I consider this the right attitude to make things better. But in Israel it is just the contrary; when you don’t say: “perfect,” people are disappointed. The loss of the critical mind is the end of everything…