Editor’s Note: This comprehensive biographical sketch was written for my mother, Bath-Sheva Kauffmann, by Lotte Cohn, a colleague of Richard Kauffmann, almost two decades after his death in 1958. It was translated from the original German by Monika Iacovacci. The introduction and notes about the author were written by this writer.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Richard Kauffmann – Architect and City Planner

Introduction

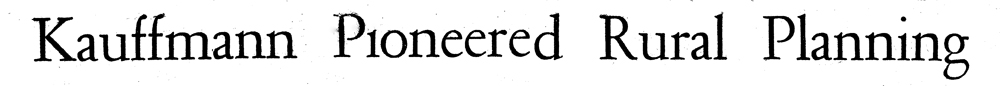

Richard Kauffmann, my father, came to Palestine in 1920 at the request of Dr. Arthur Ruppin to head physical planning for the Zionist Commission[1]. He brought with him an unshakeable Zionism that requires unconditional commitment to the land, to the people, to the work, and to the workforce. He “virtually single-handedly shaped the character of the rural sector of the Jewish state, created some of its most successful garden suburbs, introduced modern architecture, and laid the basis for physical planning in the country.”[2] During the years prior to the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, his accomplishments were prodigious, totaling well over 600 projects. His work established the characteristics of the several types of agricultural settlements that were developed throughout Palestine and later in Israel. The design for Nahalal, the first moshav, in the Valley of Jezreell, made architectural and planning history, and is used to this day in publications about Israel. In addition, he was responsible for the planning of garden suburbs near Jerusalem that remain some of the more desirable areas in which to live.

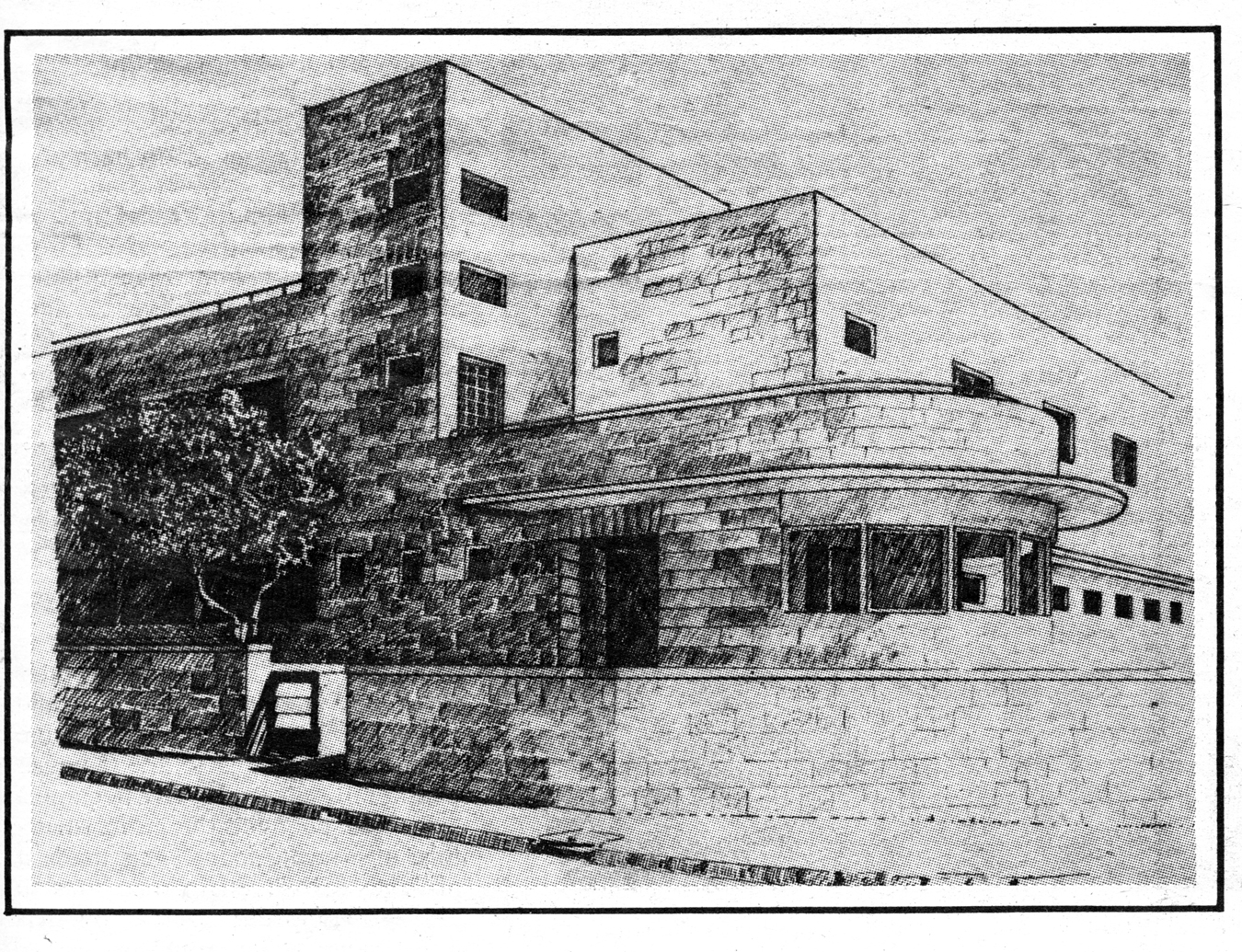

Soon after arriving in Palestine, my father opened his own planning office in Jerusalem. It handled large projects such as the plans for Carmel suburbs and the hinterland around Haifa Bay, the regional planning of Emek Hefer and its settlements, the new University City to be built on Mt. Scopus, and many other projects. He was the architect for several well-known residences, including the one used by the Prime Minister, as well as several large industrial, commercial and civic buildings. He was far ahead of his time in designing buildings that could provide relative comfort in the days before air-conditioning, using principles of environmental physics. In addition, he was an artist, whose ability to compose and illustrate how the ideas of the new settlers could be manifested enhanced their coalescence into reality. Even more important to his family, friends, colleagues and countless beneficiaries of his generosity, was his essential humaneness.

It is unexplained why his work went so long without due national recognition. Twenty years after his death in 1958, Lotte Cohn, the first woman architect to practice in Israel[3] and Kauffmann’s assistant until 1927, felt compelled to write this tribute in his honor and to dedicate it to my mother, Bath-Scheva Kauffmann. Her portrayal of the life’s work of the man, and of the man himself, is presented in a way that only a person with first-hand knowledge could convey. She brings forth in this treatise a perspective gained from being a participant in both planning and implementation. She does not hold back on describing both the successes and the difficulties of this effort. She provides her unique insight in portraying the person, my father, who was not only the visionary and planner who placed function over frill, but also was an artist who saw beauty in and the value of the landscape. But most of all, she saw in him the truly humane person that he was, concerned for others, and always willing to help, even at his own expense. It is gratifying to know that at long last more people are starting to recognize and make known to others the works of this great pioneer of Israel.

The original version was written in German, in a style that is fitting for a person both erudite and enthusiastic. Mrs. Monika Iacovacci, whose grasp of the German language and the corresponding English idiomatic expressions was essential in bringing forth the true essence of the original, did this translation into English professionally.

…Esther Kauffmann Forsen

[1] Jewish Agency for Palestine (after 1923)

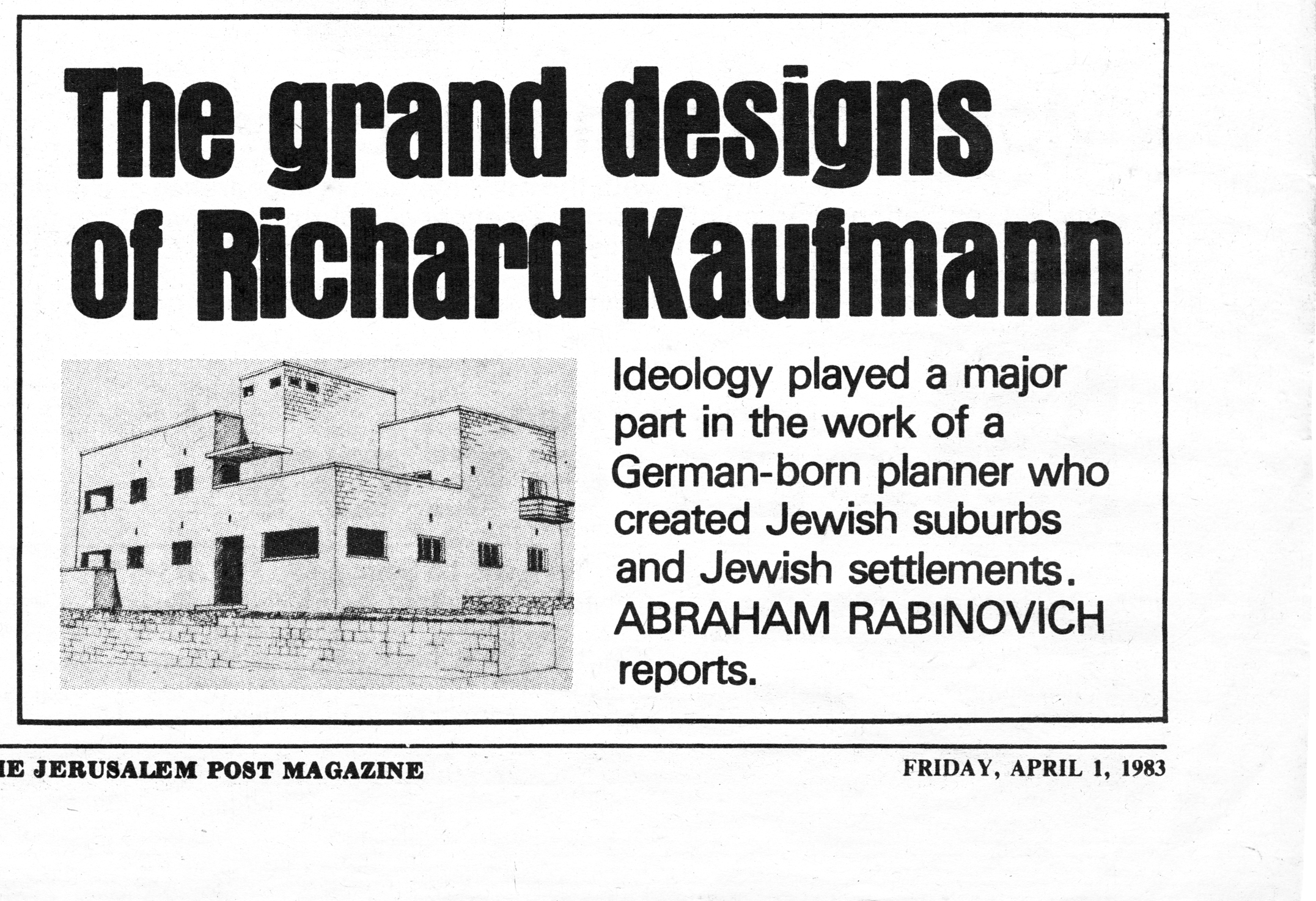

[2] “The grand designs of Richard Kauffmann”, by Abraham Rabinovich, Jerusalem Post Friday Magazine, April 1st, 1983

[3] See “About the Author…” (at the end of the article)

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

RICHARD KAUFFMANN

Architect and City Planner

Written by Lotte Cohn

For Bath Sheva Kauffmann

Translated by Monika Iacovacci

PROLOG

The year 1920 is one of the milestones in the history of Eretz Israel, it brings the first ships to the country, and the passengers have a permit for immigration from the British mandate government.

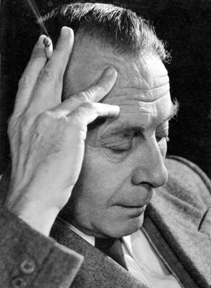

In the month of August, a young architect leaves one of these ships and enters the country. He is sent by the “Zionist Commission” and it will be his duty to set up the planning office in Jerusalem for this commission.

This architect is Richard Kauffmann. His work in the country starts with his arrival on this day, and spreads over 38 years of his life, busy years that enable him to create a masterpiece, which still today has the characteristics facing the Jewish Palestine.

Following is the attempt to depict an image of Richard Kauffmann’s life and his achievements for the importance in the construction of the country.

PERSONAL DATA

Richard Kauffmann was born in the year 1887 in Frankfurt, Main. His father and mother both came from orthodox religious Jewish homes. When one of their three children, Richard’s younger brother, dies as a young child from an infection, the father breaks with the conventional religious molds, in a naïve straightforward rebellion against the God, which he had believed in. Therefore, Richard’s adolescence proceeds in a course of assimilation to German ideology. It is the Germany at the beginning of youth revolution, the “Wandervogel” youth movement. However, it is also the time of the strong growing Zionism in Germany. Parallel and motivated by the German development, the Zionist migration association “Blau-Weise” was founded. Kauffmann is one of the founders of the Frankfurt group and their adored and loved leader. Only a few of these leaders stayed as committed to the character of these youth throughout their whole life, as he did. It was in his nature, in the simplicity of his character, in the never slackening devotion to the ideal, within the joy of creating, and the own creative strength. They kept the youth inside his character awake into the mature age of the man.

The creative predisposition appears he wants to become a painter. The pictures that he created then, are no more than studies in an impressionist style, landscapes, romantic city outlines. The sense for the quaintness inspires him greatly. Whether his talent would have been sufficient for the great artistic world with growing maturity remains to be seen. Through the influence from his father, who wants to assist his son to a middle-class existence, Richard decides to become an architect.

His studies take him to Munich, where he receives an excellent apprenticeship under Theodor Fischer, who was at that time the first of the great teachers in the field. He concludes his studies and starts his practical career in Essen; aside from other projects, his work is the planning of the residential settlement of the Krupp-Factory, Margarethenhöhe. Head of the planning office is Professor Georg Metzendorf. Shortly thereafter, he is in Frankfurt and independent. He is called to the war in 1914. For four years, he is an active soldier, fights on both fronts and receives decorations. The year 1917 finds him on the Russian front, now no longer in the front lines. He is stationed in Kowel, a town in Volhynia. A large Jewish community exists at that location and their homes are open to Jewish soldiers. The Jewish population in Eastern Europe is tied to Judaism a lot stronger than the Jewish people that were brought up in Germany. I assume that the Jewish spirit, present in the hospitable homes there, may have given Kauffmann’s Zionism a new foundation and new energy. A world opens up to him, in which being Jewish and Zionism are more alive and realistic, than the pale Judaism, which he had been taught by his “Blau-Weiss” organization. Close friendship ties him to two war comrades, Fritz Kornberg, also an architect and originally from Berlin, and Fritz Fischl, a young doctor from Czechoslovakia. Like himself, they are both ardent Zionists and will later on, almost at the same time as Kauffmann, immigrate to Palestine.

During his stay in Kowel, Kauffmann has a chance to participate in a Russian contest to build a zoning map for the Garden City Raigorod near Kharkov. He wins the first prize. After the end of the war, and demobilized, his path leads him to Christiania (Oslo) in Norway. Among fifty candidates, who strive for a position with a major company of the country, he is picked, a Jew from Germany. The projects and references he submitted had to have been outstanding in order for a foreigner to be chosen. For Kauffmann, the time in Norway is a time of maturity in skills; he fills a position contributing to great architectural and urban planning projects for city expansions. Again, he receives prizes for contests in Christiania, Bergen, and Stavanger. Kauffmann always talked about this time in Norway with great pleasure. He loved this beautiful country and its people, whose pure type just delighted him. The temptation to stay there is strong, for he is offered a partnership with compelling prospects that opens all possibilities for a brilliant career. However, when in 1920 he is asked the question, if he wanted to lead a planning office for the Zionist Commission that is tied to a project for the “Palestine Land Development Company”, he accepts the call. He is in Jerusalem in August 1920.

Kauffmann remained a citizen of Jerusalem until the end of his days. The love to this beautiful city that has no rival in the world, keeps him bound, although his work soon takes him across the whole country. True to his work ethics he wants to take the country sensually as well as scientifically. For an architect and city planner, that is the name for his professional status, has to know the land, where he wants to build and to plan, from the ground up. Kauffmann looked around.

In order to correctly appreciate the achievements of Kauffmann, one has to be familiar with the conditions he faced, has to visualize the country and the people, in the way they presented themselves to Kauffmann at that time.

T H E C O U N T R Y

I want to take the reader to the location of our work and try to recall the impression that Palestine left on me when I first saw it in 1921.

It was not yet the Israel of today, the land of the “Green Border”, it was the Palestine in a just beginning Mandate-Government, impoverished, withered Orient. Hills and valleys, plains and marshes were still uncultivated in large areas and scarcely inhabited. The stony mountain masses in Judea and Galilee face the sky staunchly; no woodland softens the rigid silhouette. The Emek Jezreel, (Plain of Esdraelon), is still barren land; only Bedouins have erected their picturesque tents and follow the scarce plant growth with their herds. As far as one can see, the valley seems abandoned and empty.

But how beautiful is this heroic scenery of stony mountain masses, the gaps of the wadis; yet it is virgin land, like it just came out of the Creator’s hand, waiting to awake.

I don’t think that there are many countries on earth that can conjure up such a variety of pictures on such small space as Palestine. From Galilee in the north, the highest part of the country, one can reach the Jordan valley in a short drive, which is located way below sea level. The river comes from the snow fields of Mt. Hermon, crashing down into the Huleh area, which at that time was a wide melancholic marsh and swamp land. This is also virgin land, an eerie silent solitude. The Kinneret-Sea is the large water reservoir of the country; its banks depict magnificent scenery during the changes of the day with the glow of the rising and the sinking sun. The river Jordan, a narrow river, remains below sea level. In many windings, it forces its path first through tropical land, and then further into the drought and desolate area towards the Dead Sea. Here, Sodom is located, the site of the ancient Sodom and Gomorrah. The region, salt crusted and withered brings credibility to the myth of the Bible. We are in the desert of the Negev, a mountain region, colorful with metallic rock. It leads down to the Dead Sea, which by the way is glowing blue and as clear, that it allows to see the fairytale like scenery at the bottom of the sea with its corals, shell rocks and strange climbing plants, populated with exotic fishes.

Whichever way one turns, the varying pictures change alternatively in a quick sequence. The coastal area is the heart of the settlement. It is the large orchard of the country. Here, one can feel dealings and change, although the harbors of Jaffa and Haifa have not been completed yet. Far out in front of the cliffs the ship has been anchored near Jaffa, in large rowboats people and freight are taken onto the shore. The Mediterranean Coast is a wide, hilly area of dunes and once in a while gains additional scenic accents from the steep hillsides. The old harbors from the Roman Era are located there, dreamily with the ruins of forgotten architectures. Camel caravans deliver the crop from the orange gardens, and other heavy loads from the small villages of the backlands to the harbor, the picture would not be complete without them. In the north the Carmel Mountains reach close to the coastline and form the bay of Haifa at the Horn of Stella Maris, which stretches to the small fisher harbor of Akko.

There had not been much tree growth at that time, and the land seemed to be almost stark. However, at places where trees could be found, the large-petals of the fig trees, the oak trees, the coniferous trees, they added special accents to the picture because of their sporadic existence; the slender tips of the cypresses, the feathered crowns of the palm trees; each tree becomes an individual monument. The delicate green of the leaves from the Olive trees throw a silvery veil across the olive grove areas.

As much as the picture changes, the climatic differences are just as strong; depending on the altitude and depth of the strip of land. The sun is hot everywhere and accentuates the scenery with sharp light and shadow. We have a distinct difference in the seasons. Strong downpours come along with the winter, which is also the green time of the year; the ground quickly dries out in late spring already, and turns yellow after harvesting the grains. There is no trace yet of green gardens that are artificially watered. Grapes and Oranges are cut and picked in the late summer and early winter. The Chamsin occurs several times a year and is a desert wind, which is a scourge for the country, man and beast both suffer, and often the young seeds are destroyed.

A quick word should be added with regard to the Arabic village that without a doubt has lent extra- ordinary charm to the scenery Palestine’s. The Arabic Fellah knows how to pick his spot, almost all villages in the mountains and hill country are located at a dominating place, open to the cooling wind and clear to the surrounding field of vision. The construction rises following the contours of the terrain; this especially gives a crowning view to the overall picture. The romantic of the picture is reinforced by the reflection of an untouched world in the dreaming Orient. Indeed, the Arabic village belongs to another time far away and untouched by the civilization of the modern age. Industry and revolution have not spread out this far. At this time, the Arabic farmer still plows with the gnarled root of a tree, he threshes with a stone studded board; he stands on top of it, holding the reins of the mule that drags in continuous rounds across the threshing floor below the open sky. Water is not available in every house; the woman hauls it often from far away, from the next well or spring. Motorized transportation is not available to the farmer, the donkey is on duty. The natural fertilizer is dried in flat blobs on the flat domes of the houses. The Arabic village mirrors the life style of the Fellahs; it is “functional” in its way and especially that gives the picture its inner beauty of genuineness notwithstanding the run-down condition.

This is the land into which the Jews will immigrate. It holds a commitment and at the same time a challenge towards the constructive creativity in the mind of the person, whose task it will be, to shape the face of the land.

Kauffmann never lost his awareness to this commitment. The respect for the scenery remained his first priority, only out of necessity the building architect has to violate the original charm of the undeveloped land. Kauffmann is a romantic. This is one of the basics in his nature. The special character in the overall appearance of the landscape, its tanginess, its resistance to the influence of civilization, the mysterious magic of the sleeping Orient has especially touched this side of his character. He had always been conscious of his responsibility, and we shall see how specific this romantic line in his character will direct him in all of his projects.

T H E P E O P L E

Neither house and settlement, nor village and city are “monuments”. They are supposed to serve the people, their wellbeing, their work, their continuous development, and their cultural needs. Kauffmann meets a new world of people. Who are these Jews, which have brought the past century and the latest decades into the country?

Pre-Zionist Immigration

The early “return to the land of the fathers” that puts a specific Jewish stamp onto the picture of the land, is the immigration of the religious Jews, which starts around the year 1840. In all the long centuries of the Diaspora one uppermost leading thought remains alive among the Jews, the faith in the Messiah. He is the driving force behind this immigration. To be close to the place, where He will enter the Holy City; to wait for him there, to die there, and to be buried there, is the basic thought of these Faithful, who now settle down in the country and build their small parishes, mainly in Jerusalem, in the west of the city outside of the old town walls. These city neighborhoods that were built here and there randomly, and without planning seem to have been built after the model of the small eastern European Jewish towns. The parcel, purchased somewhere, is in most cases located within a separate, rectangular crossing road network; the roads are narrow and the parcels accept the small individually owned homes, sometimes strung together in long rows; this is new for Jerusalem, without a front lawn and without special architectural design. The neighborhoods carry the character of poverty; the people live on the Chalukka, which are sent as Mitzvah each time, from the small eastern European communities in periodical deliveries.

The core of West Jerusalem was built from the Chalukka in the first half of the 18th century. A world separates these people from the Zionist immigration, which starts in the Eighties.

First Aliya

The catastrophe of the pogroms directed against the Jews in Russia in the year 1882 was the occasion. It started a mass emigration. It is true; the majority of emigrants headed for America but for the first time the Jews in Europe react with an interest in Palestine. The Jewish question and how current it is, as one discovered sufficiently, occupies the heads of the intellectual elite among Europe’s Jews. The money tycoons in Germany, France, England, the Moses Montefiore, the Barons de Rothschild and de Hirsch confront the work practically; a generous colonization task is started. For the first time, it is based on an economic idea: to assist the Jews that are immigrating to Palestine to get an independent existence on their property. Realization sets in, that colonization of the land and settlement of the Jews without regrouping prevailed within the Jewish population,

would not result in a healthy development. Away from the repugnant occupations of the peddler, the scrubbiest small trades, the money business, back to the origin of the farmer – to nature and land.

Based on this, the early colonies of the country prospered and will be taken through the first hard years with alternating success through the support from the philanthropical work, to settle down and to become acquainted with the foreign conditions of the country.

The first colonies of the country are “planned” in a way. Kauffmann travels through the country from Metullah to Rehoboth, from Motza and Petah Tikvah to Rishon le Zion. It is not hard to recognize that poverty and insecurity, unawareness, lacking foresight and the constant fear of attack have formed these, at that time, small settlements. The year 1920 opens up new perspectives, a whole number of these colonies will later develop into local centers, into cities. Kauffmann hardly has an opportunity to intervene significantly in this development. But the mistakes that were already made, however understandable and unavoidable they may have been, become material for thought for his own work later on.

In this time period of the first Aliya falls the heroic attempt of the BILU, who already anticipate the thought pattern of the second Aliya, namely the idea of w o r k and the community. It is a first flash and lapsing of the great basic thought about collective settlements and as such of ideological significance. However, the BILU-Colony Gedera did not become the commune, which it should have been; there is no structural sediment of the idea visible in the few old remains of building from that time.

T h e S e c o n d A l i y a

It dates back to approximately the year 1904. It does not belong within the framework of this script to mention in detail the extraordinary significance of the second Aliya for the construction of the country. It is known. Only very quickly it should be recalled that for the first time the impulse of

n a t i o n a l a w a k e n i n g drives the immigration in full force. Now, it is not only the “A w a y from the pressure of foreign nations” but the “T h e r e into the land of our fathers”, that inspires them. And at the same time, and also for the first time, the idea of own, very personal work of the individual, steps into the foreground. The first Aliya had cultivated the land with cheap Arabic work; the second Aliya cultivates the land itself by hand. It has built a new religion, the “Religion of Work”. I have mentioned both because indirectly those two strong impulses will reflect their influence in the architectonic documents. Two big accomplishments in this area are listed on the credit side of the book of the second Aliya. Not quite as “large” in its visual effects, as in its intellectual content. The second Aliya established the f i r s t Kwuzah. The founding of the first Jewish City, namely Tel-Aviv, belongs to the time frame of the second Aliya.

We will see that both of these accomplishments were significant for Kauffmann’s work, although not in the same sense. The big motivation for the continuation of the architectural idea had been Degania according to its contents. Degania was a prelude, and especially the structural mistakes showed him the way. As much as he admired and appreciated the founders and the initiative for the Jewish city Tel Aviv, it did not become the place were his creative spirit found its stimulants. He was depressed by the narrow, calculating petit bourgeois mentality, that out of necessity was leading there; the specialist in him revolted; he wanted to make it better but there was no response to his suggestions. That is why Tel-Aviv never entered his scope of work. He proved with both satellite-cities, Bat Yam and Ramat Gan, that were meant to be “Garden-Suburbs” in the South and the East at the time of their planning, what kind of possibilities could be offered for healthy planning of the charming area by the sea and in the hills. The development for these two cities took a different turn than Kauffmann anticipated at that time, they became independent cities; at any rate, Kauffmann’s basic intentions did not object to this development. Tel-Aviv however, missed its possibilities during the early construction phases; the core of the city remained crippled. It became the ugly Tel-Aviv.

TEMPORARY CIRCUMSTANCES

I have portrayed the land and the people for whom Richard Kauffmann will work. They present a wonderful incentive to him and restrain him at the same time. However, even restraints, which he has to overcome, turn into incentives. The fight against the restrictions from the outside is harder.

U n d e r d e v e l o p e d P a l e s t i n e

Palestine is an underdeveloped country, neglected Orient. The possibilities offered by the land have hardly been developed. The swamp land, plagued by Malaria, has not been drained; the fields have not been cleared from stones. The “land, where milk and honey flows” seems to be part of a legend. Wooded areas were apparently deforested during the long centuries of ruthless exploitation. The remainders of the tree growth bear witness to this. Only few highways connect the large cities and they are badly paved and deteriorated in parts. Secluded villages can only be reached via rutted paths in the sand. There is no orderly network for water supply. Springs and wells supply the arid country very poorly and inadequately. Rainwater is collected in cisterns in the cities. At places where they are insufficient, water has to be purchased from the large cisterns of the rich landowners. Arabs, carrying animal skin filled with water on their backs, display a common picture. There is no central sewage disposal, not even in the cities, and just as inadequate is the supply with electricity in this country. It should also be mentioned, that healthcare and educational systems occupy incidentally a very low position. It is more important for the city planner that the land had never been continuously surveyed while under Turkish administration. However, a land register and tenure for ownership of land and house existed. Rudimentary building laws may have existed, at least the construction and demolishing of buildings was subject to a building license. But no building regulations, as known for a long time in Europe, and no regulations for urban building requirement exist. The word urban and regional planning is unknown.

The mandate government brings improvement. The land is surveyed and a construction- and city building law is imposed according to British model. However, several years pass before the building code is developed and officially implemented, and the authorities for urban building are able to work in the various districts. The agricultural settlements are for the present not restricted by legislation, and not subject to inspections.

It is different in the cities. By now there are building authorities in all municipalities and it seems, that the provisions used to approve a building license during the Turkish time, were very rudimentary; I could not find a document in any of the old archives, which could have given any information on the subject. If one were to believe the anecdotes from this time, then the by-the-way inconvenient rules had been easily evaded by the customary baksheesh [TN: gratuity]. And there was for sure no instance at that time, which would have enforced the ground- and development policies.

Ground Policy and Planning in the Jewish Sector

When the Zionist organization in 1908 moved their operations to Palestine, it faced the primary task to acquire territory in the land and to get it ready for settlement. The Palestine Land Development Company (P.L.D.C.) is founded; their leader is Dr. Jacob Thon. Their mission is, to acquire land in Palestine and to develop it. The actual task of planning, as the modern city planner understands, was outside of their possibility and remained that way, after the British government assumed the mandate. Our work could only be piece work, a type of a puzzle-game; from whatever side it was viewed. We had the large picture in front of our mind’s eye. But all too many individual pieces to complete it were missing. The land was not ours; we could not choose the ground, it was assigned to us by the government that followed its own politics, or we had to purchase it wherever it was offered at the time. Only the State of Israel could put an end to this unhealthy situation. So, the work of the P.L.D.C. remained limited to purchasing land and amelioration: Draining swamps, de-stoning land, obtaining water and point-by-point development.

Although this unhealthy condition could cause only little damage to the agricultural planning, they were unbearable obstacles for the expansions of the cities.

Here, another complicating factor was added, the land is split into two, divided among Arab and Jewish population. The internal architectural development of the cities, especially Jerusalem and Haifa, takes place side by side and not in cooperation with each other. There was no government institution that could have promoted the intertwining of the proposed plans. There is no planning office, and “Local Town-Planning Commissions” don’t include such functions.

At times the ground that had been given was constricted in such a way that a sensible connection to the cities master plan could not be established because of already developed neighboring ground in the Arabic sector. In other cases the borders of the ground did not conform to the geographical borders, which is especially difficult in mountainous areas. The neighboring area that did not belong to us blocked in this case a naturally marked-out route and forced solutions, which in a sense violated the terrain. Such tasks could bring doubts to Kauffmann regarding the value of this work.

THE PRO JERUSALEM SOCIETY

Kauffmann’s initiation into the “British Town Planning Institute” stems from this time; he remains to be the only one in Palestine, who is accepted as a Member. The first stages in the sense of city planning are made in Jerusalem. No wonder that especially this city that has countless historic monuments telling the grand story of three religions across many centuries, tapped into the consciousness of those circles, which are in charge of the cultural care for the country. The Pro-Jerusalem Society is founded. Their goal is “The conservation and promotion of Jerusalem’s interests, its regions and its occupants”. Their specific program is a little vague but diverse. It includes, as a first priority, the concern for, what should be called homeland protection, but also the establishment of parks and open spaces, of museums, libraries, art galleries, music- and theater centers, motivation as well as the re-awakening of folk art and ethnic crafts.

It is still far from the development of a general zoning map, the time is not yet ripe for that. However, the Pro Jerusalem Society is in control and in charge over the city development plans and the city expansion, before the town planning ordinance becomes effective and prior to the establishment of the “District Jerusalem” and before it becomes subject to the “Social Town Planning Commission”.

Regrettably, Kauffmann’s work never took him to the area of the overall planning of Jerusalem; he is also officially not part of the work of the Pro Jerusalem Society. However, his indirect influence, his friendly and collegial connection with the “Civic Advises”, a government office suggested by the Pro Jerusalem Society, was without a doubt successful. He dedicates his plans to the protocol of the society for the activities in the years 1920 to 1922, and those are the only ones that came into effect at all in Jerusalem at this time, a major chapter.

I have reserved a wide space to draw the world that Kauffmann enters in 1920. Only against the background of the conditions can the significance of his works be appreciated.

NINETEEN HUNDRED TWENTY

This year marks the beginning of the Third Aliya. Following the long stagnation of World War One, life in Palestine awakens to completely changed conditions. The British Mandate Government takes over the country following the military management; the Balfour Declaration has opened the long anticipated way for organized Zionist activities for the Jews.

The third Aliya brings another type and a differently raised group of people into the country. The war is over with a victory of the combined powers over Germany and its allied Ottoman Empire. The European world has plunged into a whirl of revolution, socialist thoughts have broken through. It is a time of admirable upswings. The faith in a better, fairer world under socialist leadership rules the young people, who are bubbling over with activities, and full with active participation in world affairs, with an urge for expression in all areas of spirituality and art.

This is the world of this Aliya. It is an immigration of socialist youth that has gathered experience; Experience of a world war, toppled governments, revolutions and radical changes in all areas. It is a youth that knows what it wants, that is one unit, one political factor.

The third Aliya is especially a-religious. It does not want to save people from their demise in the Russian pogroms, and it does not want to accept or render any benefactions. It wants to establish: A Jewish land, and a Jewish nation, which will become one unit. The inner strength of the Zionist idea is finally ready for full action. That is the human material, which is available for the c o n s t r u c t i o n o f t h e c o u n t r y. Kauffmann is one of the people of the Third Aliya, he has become their architect.

C o o p e r a t i o n w i t h R u p p i n a n d T h o n

The man that has recognized the value of especially these people, and added it as an essential factor to his great idea with regard to agricultural settlements through the commune, is Dr. Arthur Ruppin. Let me briefly reflect on the contents of his chain of thoughts. He viewed his work as follows: Here was the land that should be colonized quickly and on a large scale. He saw the type of people in Europe that would make up the large immigration wave that could be expected. There are only very few farmers among them, most of them, practically all of them, are city residents, who would have to be trained to become farmers. To send them individually into the country to take on the unequal fight with the Arabic farmers who know the land, and at a far lower standard of living, that was necessary because of the undeveloped economy, would have doomed the “construction” from the beginning. Monetary means, similar to the great Philanthropists, are not available to the Zionist organization. But one factor is present, young people are enthusiastic and willing to make sacrifices. There is Degania, proof that a collective settlement is possible. The post-war youth is socialist-minded; the idea of “community” belongs to their world view. This peculiar nature of the problem calls for new methods. Economical as well as sociologic reasons point to the direction of group settlements.

It is a lucky break that brings Ruppin and Kauffmann together on this job. Both of these men, completely different in their mentality, complement each other. Ruppin entirely scientist, sociologist and economist, thinks, checks and counts; however, at the same time he is open to v i s i o n, the human possibilities of risk attract him. Kauffmann meets him from the other side of the road. He is the pioneer of the third Aliya; his artistic soul is in flames, the urge to realize the ideal of the Zionist socialist youth pushes him onward. However, he is also not at all unapproachable to realistic thinking and this is the link between the two men. The post-war modern world of architecture and city planning is definitely focused on clear thoughts; the soon following era of functionalism moves even this tendency to the extreme. Kauffmann connects with his thought structure two seemingly diverging basic intentions; he is a romantic and realist at the same time and therefore by all means receptive and prepared for the reception and the processing of Ruppin’s world of ideas. He had always been a great admirer of Ruppin. “He is much smarter than I”, he naively admits, for he has an astounding perception of his own limits. No, Kauffmann is not “smart”, the aura that springs from him and leaves a first impression is of a disarming naivety; the gift to recognize advantages; he does not understand to take detours because of strategy matters, when the straight road ahead is blocked off. But the thought content of an assignment fascinates him just as much as the formal design. Recognizing the contents gives his thoughts a sharpness that sees real possibilities, and exactly and consistently evaluates and organizes them. Perhaps it is exactly this naivety; the generous simplicity of his thinking is an asset, his spirit is not willing to accept the small hurdles in the road. By the way, his argument that a city planner has to think for decades and not just for tomorrow, are absolutely realistic.

Both men, Ruppin and Kauffmann have always had an excellent working relationship in mutual understanding. Aside from his assignment for the farming settlement, Kauffmann worked also for the civil sector, within the scope of the P.L.D.C., namely as their constant associate, advisor and planner for all new developments within the city. He also had a friendly relationship with Dr. Thon and his associates.

Even years after the official ties to the Zionist Executive and the P.L.D.C. had come apart, according to circumstances relating to the era; Kauffmann remained the “City Builder of the Country”. He was included in all planning committees; his advice was still considered substantial, even after distinct experts, who were mainly dedicated to the planning of Shikunim for the great immigration, came into the country after 1933.

Still, the agricultural settlement remained Kauffmann’s special area, the planning of collective settlements. For many years the continuation of Ruppin’s settlement remained in the hands of the by now organized workforce. Their agency is the Merkas Haklai, and the man who leads them is Avraham Harzfeld. An astounding and almost astonishing relationship develops between Harzfeld and Kauffmann. They come from entirely different worlds; Harzfeld is the Russian revolutionary of the second Aliya, possibly grew up in a tight setting of a parental home in the Jewish “Stetl”, while Kauffmann is the assimilated son of the highly developed Germany. From the background of this actual strangeness grows an affection that lasts for a whole life, Kauffmann’s whole life. Harzfeld survived him by 15 years, and remained true to him in his memory until his own end. The base for this connection is both of their unshakeable Zionism that requires unconditional commitment to the land, to the people, and the work, and to the workforce, and that is present so strong in both men that it overcomes the divide. They appreciated and admired each other extremely, each saw what he lacked in the other, in Harzfeld the overmastering original-Jewishness, in Kauffmann the artistic world and the serenity of the soul.

Only following the establishment of a large planning office by the Kibbutz movement, after the State was founded, it took the planning for urban building of the Kibbutzim, its expansion and the planning for new settlements into its own management. At that time Kauffmann’s involvement in the work processes had already ceased.

KAUFFMANN THE HUMAN BEING

The connection to these three men of the Je’schuv that built the frame for Kauffmann’s work sheds light on Kauffmann’s position towards other people, which he respects. Kauffmann always acknowledged freely the superior spirit. He was his own best critic and modest on this base. Only where mediocrity got in his way did he become impatient and unapproachable. Despite that, as the manager of his own office, he understood how to lend true atmosphere to his artist workshop. Kauffmann’s drive and his never ending zeal carried you away; however, one was free, there was no pressure of a strict regime, and with this freedom one worked better and more. The human contact between him and his coworkers was established and supported by the touching undemanding nature in his appearance and his lifestyle habits. It is true that the complete Third Aliya had accomplished its own gloriole of the Chaluz; to be a worker that was their pride that once in a while climbed to exaltation. To have nothing, to be independent from external conveniences of life, that was the generally accepted sign of that time. Kauffmann was true to these values like no other, he was Chaluz. His apartment was scarcely furnished, only a few distinct individual items, carpets, an old tankard whose special effect was brought on by a branch of thistles, bears witness of the artist’s desire for beauty. However, in this otherwise poor apartment one could come and go. An extra bed and a chair were always ready for a visitor, although the amount of plates was not always enough for the many guests. He also always had an open hand. I don’t know how many Kibbutzim expanded their number of animals because of him, that remained a secret, and I only found out by accident. And more than one of his old friends in the Galuth received their boarding card for the ship to immigrate from him. For money meant nothing to him, he gave it wherever it was needed. Kauffmann was always in a circle of many good friends, but did he have one friend? I believe that his deep-set reserve and his shyness hindered him to surrender himself completely.

What marked his personality most distinctively was the commitment to his work.

A letter dated July 21, 1921:

Dear Miss Cohn:

“When I think of the longing, the fear that I had for the land, better yet for the work in the land and of the happiness, when I received my calling in Norway in August of last year, then I can imagine how you might feel now…there are outrageously beautiful especially city planning tasks available. There is a prospect for tasks coming up that by size, beauty, and importance force one to unconditional complete commitment. I only hope that I will have enough strength to cope with the harsh conditions here with body and soul. These are mostly the people with regard to our goal…Please bring a few examples of explicit German building regulations for Cities and Garden Cities……”

This letter is by the way very long and contains many good words of advice for the trip, which at that time took 8 days, confirmed the first impression that Richard Kauffmann’s personality made on me. Not a conventional letter from an employer to an employee, which he has not met. This impression was confirmed and reinforced during the team work that started just then. Richard Kauffmann was free, actually more than that, he was consciously in contradiction with any convention, he was warm hearted and open to any human relationship; he was enthusiastic and capable of ardor. And he was an artist.

The country, the people, the circumstances of that time and he himself, his productive strength, from these four grows the accomplishment of Kauffmann, an immense accomplishment, which contributed to the face of Eretz Israel.

THE ACHIEVEMENT

Only few people will be able to remember the expositions that displayed Kauffmann’s work while he was still alive. It was always just a selection of the combined accomplishments; still the multitude of exposition pieces was surprising. There were, as the most extensive continuous work, the agricultural settlements. It is, notably, the collective settlement in its three developed forms, the Kwuzah, the Moshaw Ovdim and the Meschek Schitufi. Kauffmann himself has explained this work of his in a lengthy exposé in its entirety. The analysis of his work is interesting, not as much because it formulates exactly the thought process behind the three forms of settlement, because that is known. But Kauffmann explains how the shape of the settlement appears straight from the thought process, and the importance of how one develops from the other.

K a u f f m a n n t h e T e a c h e r

Kauffmann had learned quickly that his job would not be successful without continuous explanation and education. He never forgot to explain all the basics of his plans; he tried to bring a science into this country that had been unknown until then, a completely new territory. Lets hear then, what he himself says on this subject in his memorandum to this topic: “The city planning construction of agricultural settlements”. “…the agricultural settlements that have been founded since approximately 1870 until after the war in Palestine have more or less been developed without a plan. This is less surprising because the still young and modern city planning for construction of agricultural settlements in accordance with modern basic laws has not been given any significant attention in any part of the world… In this context, it should be briefly mentioned here what the concept for the modern city construction is, a designing science and art, which is so often misunderstood and misconstrued, by almost always assuming a purely esthetic purpose. Modern city construction has a never ending, more significant, and all embracing function. It plans to add design to each human settlement, be it a region, a city, or a village, and to shape and form it into an organism that conforms most closely to the purpose of the settlement, and which brings the best prerequisite for the most favorable implementation of its functions. Consequently, the foundation has to be laid for all issues relating to traffic, economy, health, and safety that determine the life in the settlement with respect to all questions arising from this, for example topographic and questions regarding the ground, as well as of residential nature and so forth. They should be filed in the city planning facility for the settlement and should be arranged in a way that finally one unified organism is developed that corresponds with the functions of the settlement; roughly comparable with the structure of the human body and its circulation systems…” You can see what kind of work Kauffmann takes on to convey himself and his plans. Today, this all sounds very naïve, although well known, at that time it was heard for the first time. And to continue: “…The agricultural settlement should be close to traffic structures, if possible, for example railroad or land road, but should basically be laid out apart from…..the construction of streets within the settlement has to be configured such….., that the path to work is preferably short, and the most important locations of the settlement among themselves even from the point of safety is solved satisfactorily…” Commonplace? Perhaps but at that time they were new. Kauffmann goes through the trouble and goes even further, to design this and many other articles and lectures similar to a seminar, which is supposed to lead especially his associates in related special areas into this new science of city planning. He also does not omit to show the task of the city planner as superior above the fields of activity of technicians, farmers, geologists, engineers. “…..all prior described basics and demands in the construction are like beats in music, which when loosely strung together still don’t make up a symphony. Only the artistic design is able to create a living functioning organism intuitively from all of these individual items, and thereby even the here described task becomes in the end an artistic work ….. of high significance….”

That is Kauffmann: first came the thought process for the task, but in the end the artist alone has the word. Thinker and artist, his planning was born from this synthesis. He continuously tried to bring both of these roots of his work to the people, with whom and for whom he worked. A young generation and it is now already the second one in sequence will hardly understand that Kauffmann’s work involved a constant fight for understanding, and it was a “One-Man-Fight”. The fact that he won this fight is due to his relentless idealism and his extremely strong personality that reached up to stubbornness.

T h e C o l l e c t i v e – S e t t l e m e n t

The group- or collective settlement in all three shapes is the great accomplishment of the Third Aliya. It is called the Aliyat Hachaluzim, and rightly so, although one cannot deny the first and second Aliya their pioneering spirit. For they also conquered new land, worked under hardest conditions, in blatant hardship, in a fight with untamed forces of nature, in unfamiliar climate, and all that with an untold endurance. However, the Third Aliya had been the first to write its pioneering spirit onto their flag: T h i s is how we want to conquer our land; t h i s is how we want to construct it. It is not only a fight to fertilize the ground that is taken over as desert land; it is at the same time a fight for the s p i r i t, that is to protect this work, the spirit of social attitude, of equality and justice.

This is how the youth of the third Aliya saw their task. The physical development of their settlements rested in the hands of Richard Kauffmann. He poured his best expertise and his strongest enthusiasm into this task. The sentiments of these people are his as well. And he became one of them because they were completely his. They felt it, these young men and women, and therefore the cooperation became ideal. It was a giving and taking; the thoughts of the youthful clients were often clarified only by means of the experimental layouts sketches.

Kauffmann’s strong drive with this work is indeed understandable; never has such a completely new type of problem been taken to a planner – to plan a village! Kauffmann is the first to take on such planning. However, villages, as one knows from Europe, do grow free? We find them close to an important intersection, or at a river port, or they lean close to a monastery, or to the residence of aristocrats whom are served by the farmers. New properties have attached themselves to the first shacks, large, small and purely by chance. Thus, the village expanded, often over centuries of changing cultures, and especially this growth by chance lends scenic charm to the traditional village in the European landscape.

None of these ideas are still valid in this Zionist work of colonization. Planning of a village is new territory; there is no “Model”. And this task assumes totally new requirements. In the Moshaw Owdim and the Meschek Schitufi, a previously determined number of settlers are to be relocated under identical conditions, and the village is to be erected over the course of and at all cost within one sweep. The Kwuzah [TN: a special form of cooperative venture] is a rather completely new type of a rural settlement, here only thoughts can lead the planning.

It was clear from the beginning that these new types of villages would in no way compete with the scenic picture of the historical village. They would doubtlessly have to be fixed into a rigid form of construction.

It is Kauffmann’s goal to preserve the rustic character of the picture; he loves the land and it is always his first duty not to disturb the landscape. He was successful. Whoever drives through Israel today, through the mountains of Judea, through the Amakim, through the Hule-territory, the valley of the Jordan River, can see the settlements laying one next to the other. They have reached full peak during the fifty years since their development, and one can comfortably say that this only raises the charm of the picture. There is hardly one which does not owe its development plan to Kauffmann.

Kauffmann oversaw and led the planning from the outset. A lot of problems appeared: choosing the location for the settlement, the distribution of the land, individually according to suitability, the water procurement, for these are the basics for the economical success. The land is not peaceful; the strategic position should not be disregarded. And finally the character of the settlement that has to fulfill different functions in each of the three settlement types.

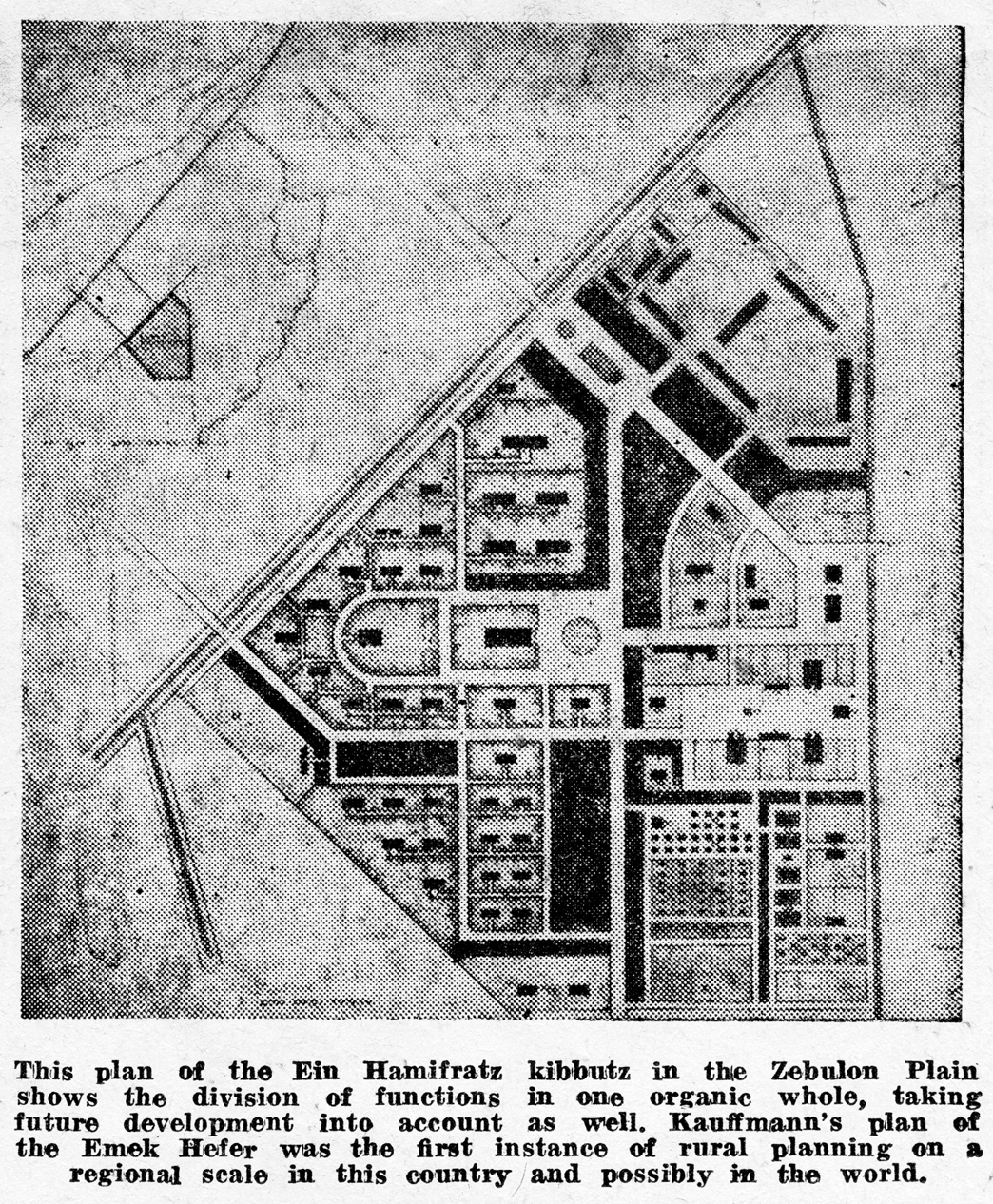

The K w u z a h a n d t h e K i b b u t z

We call a settlement Kwuzah if the number of its families is no more than 100. The Kibbutz has more than that; it could be 250 and still more. Kauffmann writes in his memorandum with regard to his agricultural settlements that the design had to create “the most favorable living conditions and most efficient work process”. So there is a clear partition of the units, the living quarters, the central work shops and magazines, the actual farm buildings. Each one of these units has to accomplish their own function; and again among each other they have to be connected in this cohesive function so that an organic whole is built. You can see how clearly his thoughts sort the plan, nothing is arbitrariness, here works strictly functionalism. But the Kwuzah also passes through development stages. From the small group of friends, which looks like a type of large family, comes according to economical necessities, the Kwuzah and finally the large Kibbutz, the village commune. Kauffmann’s first Kwuzah-Plan still corresponds with the family character of a small group; it is the plan for Geva, in Emek Yizre’el, an almost closed homestead. Apartment buildings and farm buildings are close together and border to the farmyard. The plan soon proves to be insufficient, it is not expandable and cannot adapt to the life of the Kwuzah, which has to create its own shape during the course of coexistence. Additional experiments bring other formulations of the plan. In the course of the following years, many Kwuzot and Kibbutzim are established. The complete list of Kauffmann’s plans for this type reaches the number 54. Can one speak of a typical model plan? Yes and no. Yes, insofar as each plan signifies the ideas of the Kwuzah. The functions are overall the same with only minor modifications: the functional assignment of building groups, the farm buildings, the community buildings like dining hall and kitchen, coat room with laundry facility, the residential district and the children’s village with Kindergarten and school classrooms are clearly defined, also the washrooms and sanitary facilities because years will pass, before the Kibbutz can afford to add a shower and toilet to each residence. A certain scheme can be seen in this alikeness. Still Kauffmann’s planning never neglects the special conditions that are attached to the planning because of the location of the settlement site. There is, almost the most important strategic position to be taken in account, and almost each one of the settlements functions at the same time as a stronghold because starting with day one a cloud of unrest is on the horizon. Therefore, the village has to be at the highest point of the assigned land and its water tower, the fountain of life, functions almost always as a secured watchtower. The ground conditions are also different. The position of the wind has to be considered, an important factor, especially in the low valleys of the land, where the climate is a killer and detrimental to the performance of the workers. Mountainous or flatland, connections to the road systems of the country, number of members, these are the variables that add a different face to each Kibbutz. They obstruct any schematizing. As a matter of fact, none of Kauffmann’s plans resembles the next. Each one is inspired by the scenery that the settlement has to adapt to. Kauffmann’s plans are always eminently scenic. The inner path leads within a conscious feel for space from one district to the next, and centers in the complex of community buildings that will for many decades become the dining hall. Much later a cultural center is added on, a theater or an amphitheater, a library with study rooms, a hall for memorials, or even a hall for recreation. However, such developments are far in the future. From the multitude of cultural buildings you can see, which undreamed-of development the Kibbutz will undergo. The original Kwuzah was poverty, hardship and often even a lack of the bare necessities, extreme self-sacrifice and rigid resistance. The great Kibbutz: that is economical success, beautification of the daily life, to go with the spirit of times, cultural growth. In reality are the large Kibbutzim today the center of cultural life for the whole area. Theatrical performances, concerts and scientific lectures; all artists visiting from abroad are used to perform at the Kibbutz theaters across the country.

Did the founding group of the young workers expect such a development? That can hardly be assumed. However, Kauffmann must have envisioned this; his plans are very flexible. They take a possibly large development into account without giving up the scenic value of the whole. This could not always turn out well. But if we compare the settlement, how it still exists today, 50 years later, with its basic plan, it shows clearly that it survived such development, even if the picture has changed.

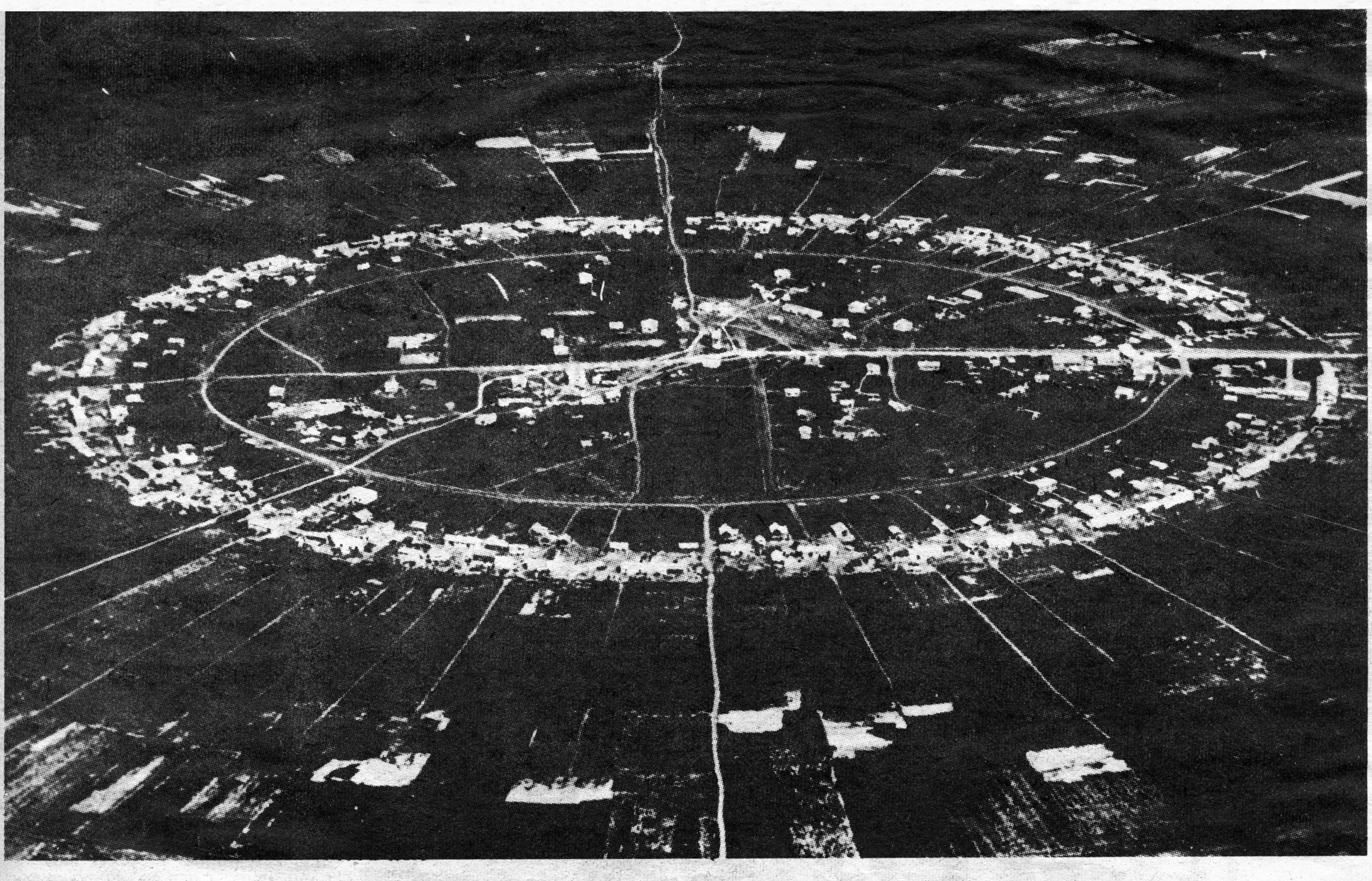

T h e Plan type o f t h e M o s h a v O v d i m, only appears simpler and more schematic than the Kwuzah-Plan; it is the result of a work-in-thoughts with tighter bonds than the organism of the Kwuzah required. The creative play of fantasy has left little room. The first Moshav-plan came from a design that should be called a diagram of Moshav-thoughts. It is the result of close cooperation with Eliezer Joffe, the man who formulated the idea of the Moshav. It is the plan of Nahalal. It was published many times … and criticized often. Kauffmann himself took a critical look at his work, when all streets were laid out and all houses built. He disengaged from this all too strict form in later designs. Nahalal is located in the Emek area, where only a few slight peaks break up the flat plains. The place that was designated for the village was clearly the most favorable: a hill almost exactly egg-shaped. It was tempting to the utmost to use this shape. In this way, a plan comes about; who’s only inside road development is the shape of a harmonious ellipsis. Both axes are the approaching and outward roads. The top of the hill carries the community buildings, surrounded by a circle of “craftsmen parcels”. The parcels for the settlers are located at the large Ring Street, alongside the outer rim; the length of their fronts is identical, and also the width of their front lawns, the houses are all on one construction line. Only where the access road cuts into the ring, are differently shaped parcels held ready for public buildings; they will form a type of an entry place. The “Women’s Jewish Zionist Organization” is building an agricultural school for girls at that place; still today, well trained women leave from there to all branches of agriculture into all settlements of the country. The plan of Nahalal is extremely simple. There is no question that it fills the requirements of the Moshav-idea in an exemplary manner. However, it neglects that even the Moshav Ovdim will experience evolutions, and not necessarily remains in the shape it has been designed by the founders.

You have to admit, that Kauffmann’s plan is inflexible and each change would be a mutilation. It is even in its uniformity poorly assessable, it does not “lead”. An agricultural expert tells me that the trapezoid shape of the parcel makes the tilling and planting of the acre more difficult – I cannot make a judgment with regard to this. In short, Kauffmann himself was skeptical, he probably saw the flaws. Contrary to that is however a statement by one of the settlers himself from recent times. Nahalal dates back to the year 1921. During a recent inquiry whether criticism existed for the plan, the answer was: We love our Nahalal-Plan just the way it is.

Later Moshavim are constructed more open and alive without violating the Moshav-idea. The equality in the size of the parcels leads to a consistently distributed development; the construction of the village is transparent for the idea. The question could arise whether the “crowning” by the community buildings proves to be a lucky solution. The essential community buildings, first of all the “public building”, are a concept, which is missing in European villages. It contains most of all a hall for meetings and for conferences, for cultural events; furthermore the town hall, and perhaps a few other cultural rooms, the pharmacy, where the doctor and the community nurse are ordained, a kindergarten, and perhaps a school; not every village has their own school, the children of many villages come together in the district schools. These buildings make up the r e p r e s e n t a t i o n a l character of the center, that at best could constitute the “Crown” of the village. But the actual breath of the community is the joint work for the ground. And their constructive deposits are more or less the i n d u s t r i a l buildings, the equipment park, the silos, the creamery, and the building for egg shipments, craft shops and shacks. Buildings like these are missing the monumental moment, especially on a small scale, like it appears in a village of 100 families. You would think that these buildings are separate from the intellectual center and indeed, if you drive through Nahalal the feeling remains that something is missing; the center that you look for, because the plan requires one, it is not there; instead a number of shacks and small utility buildings in wide open yard areas among which the small community buildings almost disappear.

T h e M e s h e k Sh i t u f i is a consolidation between Kwuzah and Moshav Owdim, as we have seen already. And it complies with the plan. The residential buildings are strung together; no economical building is attached; only a small flower garden surrounds the house. The common farm yard is, like in the Kibbutz, a separate unit, not within the center but at the access road. Bordering the fields it is easily expandable, if changes take place in the economy, for example if industry attaches itself, like it really happens quite often in the future.

The Centrum only holds the cultural structures. They also have plenty of extra space; there will be room in case someone wishes to add more buildings. Because like I already said, it is the great desire of all Israelis, even and especially under working conditions to learn, to tend to the arts and any kind of spiritual activity. It should be added here that in later years a number of villages constructed special centers for vacation courses that are meant for other group meetings and seminars. Aside from teaching and working halls, they also include guest rooms, which are utilized for weekly accommodations of course participants, domestic and foreign, kind of like a youth hostel.

The worker settlements lend basically a new face to the land, and I emphasize Kauffmann’s settlements because they were planned exclusively by him through many decades. It is not overstated, if one claims that they still today represent the Jewish Israel. This accomplishment of workmanship is unique in the world, no matter how many attempts were made to repeat or modify it in other countries. It is Kaufmann’s accomplishment and his alone that it stands out so perfectly in the scenery. The picture of the country that had only been ruled by an Arabic village and the few settlements of the German Templar communities prior to the settlement by the Jews is now enriched with a new type of fresh life accents.

When looking at the designs for Kwuzot and Moshavim it becomes evident, that the Kwuzah drawings show a stronger distinct tendency for the route planning and the development schematics, even a layman can see it. With it, you can almost prove that the form of the construction is unmistakably shaped by the content. One has to admit that the commune showed a more consequent shape of lifestyle. The Moshav Owdim as well as the Meshek Shitufi reserves a remnant of middle-class and individualism for themselves. The person in the Kwuzah is therefore the more clear type of the revolutionary in socialism; and therefore is the Kwuzah-plan clearer and more significant than one of the other collective settlements.

I have covered the agricultural settlements in Palestine in that much detail because they especially show the creative accomplishment within the city planning of the early Zionist Aliya. It has been discussed at many places and from all point of views. One has tried to learn from it, to copy it; however, to no avail. The Kwuzot and the Moshavim are the fall out of a once in a lifetime interplay of spiritual and ethical forces, so that a repeat at another place and with other people is unthinkable. It could only be done by the Jews and only in Eretz Israel. The interpretation of the finished picture, which Kauffmann created, remains the model to date.

P l a n n i n g f o r t h e m i d d l e – c l a s s s e c t o r

It may be that Kauffmann’s accomplishment with regard to agricultural settlements is more obvious in as far, that it depicts a closed and unified whole, and also has remained more or less as a symptom of a certain intellectual world untouched, so was his work in middle class city-settlements no less important.

The Zionist immigration had tapped into city land even prior to World War I, and built suburbs and founded new cities. In Haifa, Herzlia and Hader Hakermal rise on the slope of Mt. Carmel. From Jaffa, the Jews migrate into purely Jewish quarters and finally Tel-Aviv is founded. But all of these establishments are more or less just parceling, it can hardly be called planning in a modern sense. Kauffmann is the first to mention this concept of “planning” and to help the people to understand this term.

All of Kauffmann’s suburban settlement plans included the label Ir-Ganim, Garden city, before they received an official name. They went through different development stages over decades. Were they “Garden Cities” in the true sense of the word, like the European founders of the Garden City-Movement? Let me add a few words with regard to the explanation.

The first garden cities came about from the well-meaning spirit of the industrial tycoons, and were meant to help the workers out of the barbaric living conditions of the slums in the metropolis. That was the beginning. The term “Garden City” was characterized by Ebenezer Howard, whose thoughts had deeper roots. His politics started at the “amazingly growing spread of the metropolis” and leads to the construction of new centers, that can only be build by a real community. They are supposed to include everything that is necessary for life in a commune: provision of employment, commercial and social life, and its cultural needs. I don’t want to lose myself in details, the reader is aware of them. The enthusiastic agreement, which the “Garden City” found even in layman’s circles, rested in its social contents and in its esthetic effects. It deemed to be a new healthy method to expand the city, in a type of fraternization between city and nature. To the layman the picture displayed a settlement of small homes with lots of greenery and gardens, with easily accessible shopping centers and community buildings, with neatly tucked away small industries, lots of play and sports places, all surrounded by a green belt, that never to be built on, that was supposed to keep all the bad influences of the closest large city away or at least put a damper on them, and to avoid a consolidation.

Kauffmann’s garden cities are neither of both, not the neatly living quarters of the industrial concerns, or the “new cities” that would have belonged to the area of country planning. The Palestine of the twenties missed the circumstances for both. There was no big industry and there were no gigantic cities. But the word “Garden City” has a ring to it; Kauffmann uses it, more for its propagandistic value than for it sociologist contents. He knows that this lacks the basis. But he takes over something else, that is common to both plans, although not at the same level and sense. The settlements for the workers of the big industry and the new cities shall both include the residential developments that fit the modern requirements including, as the name already states, gardenlike grounds, they are to be light, hygienic and pleasant to the eye. The beauty, so Kauffmann stresses all the time, is not only the sole nor only the foremost object of the garden city. Nevertheless, the visual construction of the whole is in his planning the progression of the development, from flat building up to the intensified high rise and to the accentuated center, the “Crown” is monumental, if this word can be used in the sense of the deliberate visual design. His plans, as much as their root is functionality, are captured architectonically. That should not surprise us. City planning is even in Europe still not the highly differentiated science that it will evolve to much later. The time has not yet come that forces the enormous problems, which the planner faces today. Only the gigantic magnitude of the metropolis forces the transportation technology to develop its own science. Only now the sociologist and the psychologist take possession of the city design. “Eruption of the population”, “Environmental design”, and “Contact friendly development” had been unknown vocabulary and the city planner just recently became familiar with these terms.

For the Palestine of the twenties, such problematic is still far away from the city planner. There are no large cities and no slums inside the Jewish sector, and there is no crime among the Jews, no alcoholism, no murder, no burglars and no thieves. Kauffmann’s suburban settlements belong to a different step of development. They will not and are not to be anything more than expansions of the city they belong to. A neighborhood that is a closed community; and he shaped it in the language that his own time was familiar with. Kauffmann never started a job without familiarizing himself first in long walks with the area, his technical possibilities with regard to marking-out routes and parcels were considered on the spot, and he took in the scenic attractions. He himself is the one who mostly influences the program; he achieves, often in fights, the allocation of land for public buildings and green spaces, in short, he alone does, what later on becomes a task for a whole working group of experts, always in a fight with an administration that uses the necessity of an extremely tight economy as an excuse for their first and last argument. In as much as the Jewish Palestine was very poor at that time. It is astounding that under these circumstances a number of suburban settlements originated, which have preserved their character, such as Kauffmann had planned it.

Many of these neighborhoods were later on taken in by the city, some developed into separate cities. In other cases, like Bet Hakerem near Jerusalem, the development was so forceful that the face that Kauffmann had given the original settlement is hardly visible any longer. In others, the Carmel city near Haifa, the planning was preserved almost without changes. Nowhere did the basic lines of his development get in the way.

It is impossible to compile a complete list of Kauffmann’s city plannings. Many of them, in all cities have been overrun by developments and are no longer visible. I only want to remind you of our well known towns and city districts that have to thank Kauffmann for their first city plan, because it has been forgotten.

In the J e r u s a l e m district this concerns the suburbs of:

Bet Hakerem, Talpioth, Rehavia (North), Katamon (West), among smaller inner city sections.

H a i f a includes:

Bat Galim, Neve Sha’anan, the Carmel city, Central-Carmel, West-Carmel, Achusa, the settlements in the bay of Haifa.

In the S h a r o n – district:

Ramat Gan and Ramat Chen, Bat Yam, Ramatayim, Herzlia, Kiryat Ono, Tel-Litvinsky.

Near T i b e r i a s:

several city expansions (Ramat Tiberias).

Countless smaller improvement plans could be added, however, the value of an achievement is not shown in numbers; it is the understanding and the struggle that makes Kauffmann’s works so valuable, and in its time so exceptional. When looking over the many planning documents it becomes evident that all of these projects are particularly detailed. The parcels are determined. Kauffmann keeps this parceling that is used by the surveyor to mark out the land and copy it into a work plan, under his control until the end, just like he holds on to the final word with regard to marked-out route and profile. These are also part of a blueprint. Furthermore, he leaves detailed information on the building lines and suggestions with regard to the placement of the houses. Also listed in the details are the principal development with public buildings, their grouping in large spaces is also drawn-in as a suggestion. And finally the planting of trees on roadsides, avenues and places belongs into the plan; he will oversee this project, be involved in the selection of the plants when the time comes. Today’s planner approaches his tasks differently; he delivers tables and diagrams first and his plans do not get lost in details. A younger generation rejected Kauffmann’s plans as formalistic and “scenic” in a denying decision for the city planner. Nothing could be more wrong. Kauffmann first reflected on his plans, function was top priority. But the constructed village will change the scenery, this scenery that he loves so much. He can feel the responsibility and will, if at all possible, avoid deforming mistakes. Still another aspect leads him; the drawn picture makes the plan, often convincing, and more convincing then a verbal explanation. It is a handle, to win over the client for the value that can not easily be conveyed in words. Kauffmann is tactician enough to use this handle. One thing has to be admitted, there is a contradiction between his always stressed functionalism and the acknowledgement to be part of the artistic world. He is an artist and he even acknowledges it; he gives the free play, the “Music” of the drawing of the town planning plan, a superior place. However, strictly carried out functionalism carries beauty in itself, and should exclude freely acting out of fantasy. In so far the upcoming generation has dismissed and passed him. This judgment completely misjudges the importance of the work. Kauffmann’s plans belong to the time, in which he was schooled and can only be judged from the field of vision at that time. And it has to be stressed again and again, what kind of foresight he used to see ahead the possibilities of this small underdeveloped country, and the new ideas, revised according to these possibilities, that infiltrated with admirable enthusiasm.

T e l – A v i v M i s s e s a Ch a n c e.

The reader will be unsuccessful in looking for Kauffmann’s influence in the development of Tel-Aviv. I indicated earlier that from the beginning, he could hardly adapt to the narrow petit bourgeois mentality that Tel-Aviv still had even after the war, when the view should have been more open already. On the other hand, the people, who should have been leading Tel-Aviv’s development, were inapproachable to his generous far-sighted ideas. The only city expansion plan that he suggested for Tel-Aviv fell through. The plan is interesting; it shows how far ahead Kauffmann was for his time, and how much damage that still today has us suffer bitterly, could have been avoided by following his plan.

The Palestine Land Development Co. had acquired a piece of land along the coast to the north and had assigned Kauffmann to work out a plan for the development. They are the grounds “Amin Nassif and Matari”, named after their Arabic landlords, who had sold them. They reach to the north of Allenby Street until approximately Mapu Street and from the coast towards the east until the other side of today’s Ben Yehuda Street.

Here are excerpts of the report accompanying the plan and dated July 1921: