Editor’s note: This page is under construction and is not complete. Several more plates have to be scanned and made available via links. Plates are referenced by “Pl. xx” where xx is the plate number. The first plate in the series is Plate 12.

_________________________________________________________________________

A Brief Survey of Facts and Conditions

To understand the construction of the new Jewish settlements in Palestine some knowledge is essential of the character and objects of the Zionist movement, which aims at the settlement and revival of the Jewish people. This most important basis of Jewish colonisation in Palestine can, however, be only very briefly touched upon here.

The aim of the Zionist movement is expressed in the so-called Basle Programme: “Zionism strives to obtain for the Jewish people the erection of a publicly proclaimed and legitimate Homeland in Palestine.” One of the most essential conditions necessary for the attainment of this aim was presented by the well-known Balfour Declaration and its ratification by the League of Nations—foundations which, outwardly, offer a means for the realisation of Zionist ideals.

The driving force of the movement is founded in an inward rejuvenation and concentration of the Jewish masses. The only people in the world which for centuries had to live without a country of its own, without a national culture and therefore without freedom, is now striving in its ancient homeland, Palestine, towards the self-realisation necessary for the existence of a free and creative body of people. The first essential in this direction is their conscious turning towards the productive spheres of agriculture and industry, i.e., nothing less than their process of domiciling themselves. This reversal of previous modes of existence already set in with force when the later Zionist colonisation began, and the younger generation in particular have returned in large numbers to agriculture.

That this violent reaction of recent times should have called forth passionate attempts to find new forms of social life is only too easily understood in the case of a people which has such strong religious leanings as the Jews, the people which from Palestine gave to mankind the Bible.

Economic Possibilities

Palestine was at one time a very fertile country. The neglect of centuries has greatly damaged its economic possibilities, and the most resourceful and devoted work is needed to bring it back again to its agricultural zenith. Herein, as well as in the industrial manufacture of its agricultural products, and of the natural raw materials of the country and its hinterlands, lie the potentialities of productive activity.

The economic and geographical conditions of Palestine in the region of the borderline of three continents made the country famous already in olden times as a prominent centre for trade and commerce. With progressive agricultural, industrial and a commercially sound development great possibilities will arise again.

Geographical Structure

Pronounced lines running from south to north are characteristic of Palestine’s geographical structure, with but one breach in a west-easterly direction. These lines from south to north, starting in the west with the coast line, follow an easterly course, as a result of the alternation of plain and mountain—the wide plain extending along the coast from south to north, the mountain ranges of Judaea, Samaria and Galilee, the deep hollow of the Dead Sea and of the Jordan Valley, and further east, the range of the Transjordanian mountains of Moab and Ammon. The most strongly-marked west-east breach through the mountain range, commencing at the Bay of Haifa, is formed by the Kishon-MegiddoEsdraelon plain. The most fertile lands for farming and settlements lie mainly in the region of the plains, so that most of the land required for Jewish settlement has been acquired here.

The Character of the Landscape

The character of the landscape in Palestine is peculiar to itself and is very impressive, particularly in the mountainous regions. The mountains, completely bare, intersected by deep Wadis (mountain valleys containing water only in the rainy season), their magnificent lines and silhouettes unblurred by trees, produce an extraordinary effect by their largeness and dynamic qualities, imbuing the landscape with a heroic character. The fierce light of the Eastern sun, the glowing effects of colour during the transition between night and day and day and night, perpetually changing, continually different, according to season and atmosphere, enhance and accentuate the powerful impression produced by this bare mountain region. Its very existence and power call for a creative effort, which a genius might perhaps succeed in. Our task is to clear this way, to keep the summits of the mountains free for the monumental buildings of the future, to push settlements towards the higher regions. Plant the mountain valleys and slopes with trees, but leave the most characteristic contours unblurred, ready to receive the pinnacling settlements. Arab villages, seemingly growing out of the mountains, make an unforgettable impression.

As is quite natural, both climatic and agricultural conditions call for the settlements to be placed on the breezy heights, and for the plantations to be laid out in the wind-sheltered valleys, whose good vegetable soil and greater humidity make them more favourable to cultivation than the wind-swept, rocky heights.

Zionist and other Land Colonising Societies

The Zionist Organisation has created various Societies for the acquisition and amelioration of land, the most important of which may be mentioned here. The central agency for purchasing and selling land is the Palestine Land Development Company. The Zionist colonising society is the Agricultural Colonisation Department of the Palestine Zionist Executive. The Zionist agricultural settlements are established on land acquired by the Jewish National Fund, a donation fund, which acquires land as the inalienable property of the whole Jewish people. It grants the land on hereditary tenure, and is thus not only a land reforming institute in the most radical and idealist sense, but by this solution of the land question lays the first and most essential foundation for a satisfactory system of town planning in the settlements. The fact of its being a gift fund unfortunately limits its scope, so that some land also passes into private hands. Thus, through the agency of the Palestine Land Development Company, lands are transferred to companies, of which the American Zion Commonwealth and the “Meshek” are the largest. An extensive colonisation scheme was also carried out by the Jewish Colonisation Association (I.C.A.), a creation of Baron Rothschild’s, which, however, cannot be dealt with here. Practically all the settlements for which I have worked out the plans, and the most important of which will be described below, owe their existence to one or other of the above-mentioned colonisation bodies and land societies.

Aspects of Town Planning Development in Palestine

Taken as a whole, Palestine offers favourable opportunities for her architectural development. The sins committed in European countries in this respect, particularly in the latter half of the nineteenth century, in many cases exact the penance of a difficult and costly process of destruction prior to a recourse to sound and economic construction; and that only where settlements have not to be rebuilt entirely. Urban and rural town planning started under far more favourable auspices in Palestine than elsewhere. Here virgin soil awaited cultivation, very little poor work of any sort existing, and the mistakes committed elsewhere served as a warning example and helped to further an organic growth adapted to the special needs of the country. The fact that this opportunity has not been fully taken advantage of is regrettable, but cannot be discussed here.

It is necessary to point out that the special conditions attending Zionist settlement in Palestine also brought the town planner a mass of fresh tasks and problems, which were not lessened by the absence of previous material to work upon in modern town designing in the East, or in earlier work of a general kind, such as agricultural settlement and so forth. This will receive mention further on, suffice it to say that these conditions increased the attraction of the labour.

The Field to be Covered

Summoned by the Zionist Organisation from Norway in 1920, where for one-and-a-half years I had been co-operating in large town planning schemes, I found an extensive field of work in Palestine, which, as time went on, grew steadily. At first, it was mainly a question of plans for garden suburbs and agricultural settlements; later came along sites whose character marked them out for towns. The three different types of settlement are dealt with below in four divisions :—

(1) Garden Suburbs.

(2) Urban and

(3) Rural (agricultural) settlements, and

(4) Regional planning.

I. GARDEN SUBURBS

The lay-outs adopted in those cities of Palestine which come most into question for Jewish settlement, that is to say, Jerusalem, Jaffa and Haifa, were at first far too congested, and in many parts, unhealthy. To avoid these narrow confines the new settlements tended towards the outskirts of the towns, where, too, land prices were comparatively low. This tendency, which is noticeable all over the world to-day, is natural in such climatic conditions as prevail in Palestine. Unfortunately, in some places, the settlements have grown up at a greater distance from the towns than is quite compatible with organic development. Most of the garden suburbs which have risen in this way are situated in particularly beautiful spots. They are the usual type of garden suburb, except that detached houses are numerically more prominent here than in an analogous European settlement. Owing to the marked individual character of the Jewish urban settler, semi-detached houses are comparatively rare, and rarer still terrace houses, which it is hoped to propagate in the near future for cottages and labourers’ settlements.

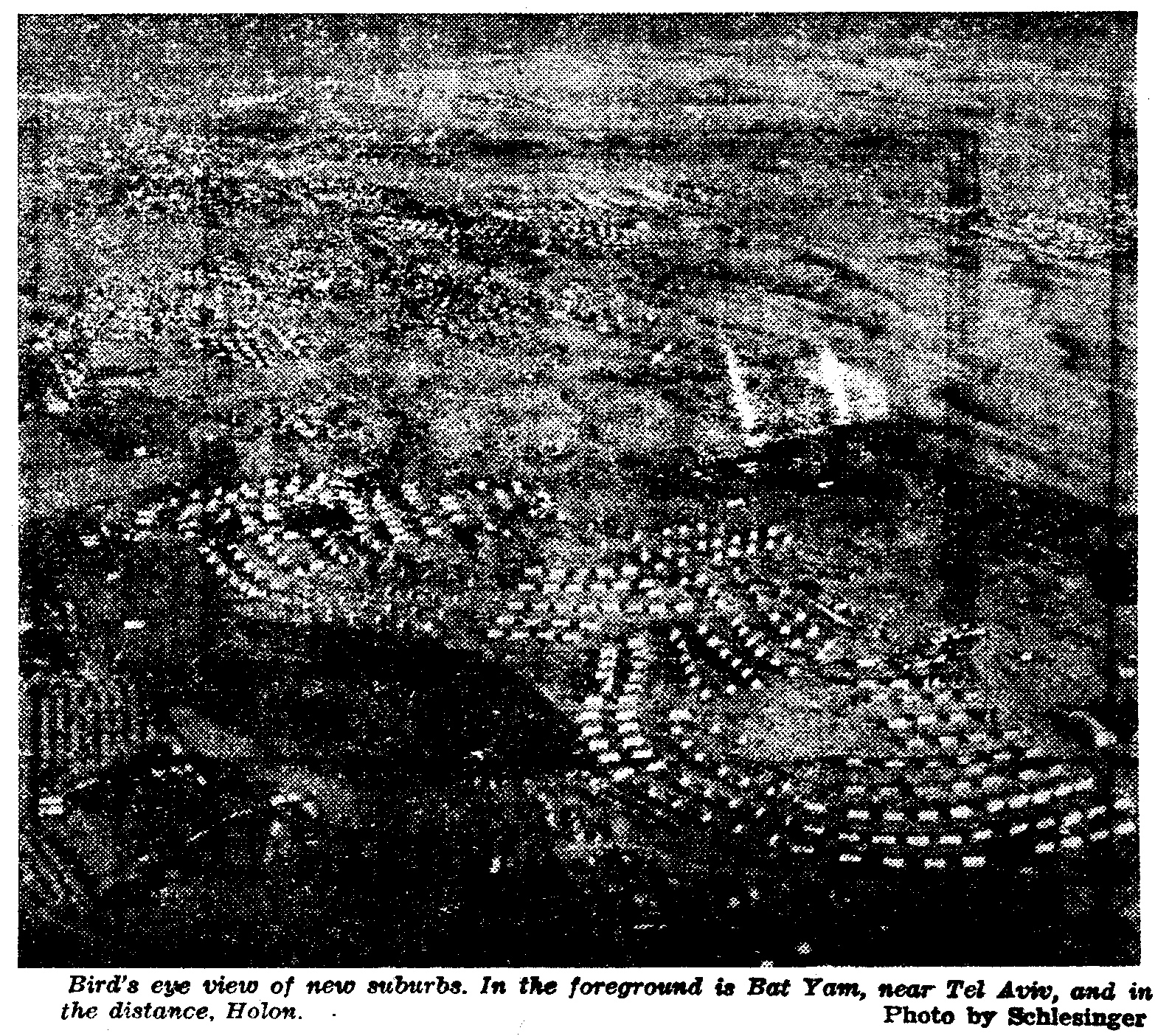

Mention will be made of only a few typical examples of the numerous garden suburbs, both those designed and those in course of erection. The earlier garden suburb near Jaffa—Tel Aviv—will not be included among them, as it has now grown into a town of more than forty-thousand inhabitants, unfortunately defying all efforts to make it conform to a systematic scheme.

Garden Suburbs near Jerusalem

The garden suburbs in the neighbourhood of Jerusalem (Pl. 12) were designed for the most part to lie south and north-west of the town. They are partly in process of building, partly completed. The largest is Talpioth (Pl. 13), situated on the high road to Bethlehem, to the south of Jerusalem. The area of Talpioth, comprising about 1,100 Dunams, (1 Dunam, the Palestinian land measurement unit, is about 900 sq. m.) is in the shape of an extenuated mountain crest, of which the longitudinal axis runs somewhat parallel with the Bethlehem Road in a south-northerly direction, its highest point reached in the southern area, some 45 m, above the Bethlehem Road. From practically all sides, especially from the summit, there is a magnificent view over the mountains in the west, over the Jordan Valley, and the Dead Sea in the east, and the steep Transjordanian range of Moab and Ammon in the background. Two Wadis extend eastwards down to the Jordan valley.

The natural shape of Talpioth decides its architectural construction. The cone of the oval-shaped mountain is being crowned with monumental buildings conceived in an imposing style. Here at this culminating point, is to be the practical and ideal union of all that is lofty and necessary in a human settlement. The dominating summit is encircled in a parallel circumference by terraced roads one below the other down the whole stretch of the mountain slope. Roads for vehicular traffic lead to the top, and at right angles to these roads, and taken up as far as the top of the eminence, a monumental flight of terraced steps, bordered by trees, rises from the Bethlehem Road, intersecting in its perpendicular course the sweeping terraced roads. Following the curves of these terraced roads, the groups of houses surround the hill, culminating in the buildings which crest the summit.

The course taken by the streets lying to the north, as well as by the buildings on them is facing the town and the Temple site in a northerly direction. A main avenue, as backbone of the whole, runs from the entrance square across the height, sloping downwards to the adjoining extension area of “Mar Eliash.”

The plan provides for plots of approximately one dunam each. After deducting 28 per cent. for streets, public squares, for plantations and sports grounds, some 800 plots are left. As regards the public buildings, space is made for a synagogue, and a people’s club house on the summit, and at other prominent points a town hall, a school, a small theatre, a post-office, etc.

Beth Hakerem.

A fuller account will be accorded here to the settlement of Beth Hakerem (Pl. 14) than to the other garden suburbs to the northwest of Jerusalem. (Editor’s Note: The plan of Beth Hakerem was mounted with North facing down in the original plate.} The foundations of this settlement are, I think, the best of any suburban settlement I have yet planned for Palestine. This fact affected favourably not only the original plan, but also its execution.

The area of Beth Hakerem, comprising approximately 280 dunams, is situated in the north-west of Jerusalem, 1 km. off the road to Jaffa on the way to the Arab village of Ain Keren. It has the typical formation of the Judaean mountain region, characterised principally by a hilltop. The characteristic form of the site, with its rising cupola, decides the structure of the settlement. The groups of streets and dwellings commence at the slope and belt the hill in rings, growing narrower and narrower, until they cultimate in a group of public buildings on the summit.

An attempt has been made here to give shape to an idea which originated from the nature of such a settlement and such a mountainous area. The settlement itself, and the mountain on which it is situated, are to be crowned with a group of monumental buildings, which will serve the spiritual needs of the inhabitants.

Extending along both sides of the middle hill are two Wadis in the shape of terraces, widening to a deep hollow at the foot. These Wadis contain the best of garden soils. The vegetable mould washed up in the course of time by the rocky treeless mountains has been deposited here. They form two natural strips for laying out as parks, their position alone marking them out for the main axis of the rhythmically curving network of roads. The natural terraces have been incorporated into the plan in the simplest manner. The manifold Palestinian plants and tree varieties afford a welcome opportunity for architectural landscape gardening, the borders being lined with tall, dark, trimmed carob trees, employed with inner beds of the delicate light foliage of pepper trees, while sombre cypresses tower above them all. The hollow at the lower end of the two green strips in the Wadis offers a favourable means for laying out an ideal sports ground. To this hollow, the sole flat point of the whole area, the mountain walls descend in steep terraces, forming a natural amphitheatre of rare beauty, which, at a relatively low cost, can be turned into a sports ground with natural terraced platforms. By a fortunate chance the longitudinal axis of this hollow faces south-north, so that the players, who only play mornings or afternoons, always have the sun and wind from the side and never from the front and will never be against sun and wind.

Two other suburban settlements in the immediate vicinity of Beth Hakerem may be briefly mentioned here, the one the so-called Montefiore Settlement (from funds provided by the Montefiore Trust), the other Bait-u-Gan (Pl. 14), situated on a beautiful mountain slope with cupolaed site, the latter measuring approximately 800 dunams.

Settlements near Haifa

If Jerusalem can be looked upon in advance as the cultural centre of Palestine, Haifa (Pl. 15) may also be regarded as certain to become the industrial and trade centre. Her economic and geographical advantages make this assumption appear perfectly justified. Haifa has not only favourable inland communications; she is also the starting point for the mercantile routes to the neighbouring countries. The west-east gateway through the south-northerly mountain mass referred to above, begins at Haifa. Already it is the starting point of the railway line to Eastern Syria, the Hauran and Transjordan. The line to Egypt starts from Haifa, as does the line to Acre, now to be extended to Ras-el-Nakura, for the purpose of connecting up at Ras-el-Nakura with the Syrian line to Aleppo and Beyrouth, Constantinople-Europe. Haifa is also the appropriate site for constructing the Palestinian port. The coastline of Palestine runs practically straight, in a more or less south-northerly direction all along the Mediterranean shore. At Haifa alone does the Gulf of (Haifa) Acre form a natural bay, in itself the greatest asset in building a harbour.

The local formation of the ground of Haifa and adjacent regions favours these conditions still further. In the western part of the town and bay Mount Carmel rises to a height of some 350 metres. In the northeast an extensive, well watered plain stretches beyond Acre to the mountains of West Galilee. The fact alone, that not only the most prevalent, but also the purest and coolest breezes, blow from the west, i.e., the Mediterranean, marks out the western mountain district as the most suitable residential quarter, while the eastern portion of the plain, with its flat expanse, offers the best opportunities for traffic and industrial development. With a climate which, due to Mount Carmel’s height, is temperate even in summer, a more ideal residence than Mount Carmel can hardly be imagined for Palestine, or for the East generally; and in thus combining mountain and sea air Mount Carmel has a promising future as a health resort.

The topographical structure of Mount Carmel is, as may be gathered from the attached photographs, extraordinarily varied and interesting. This far-flung mountain line, intersected on its eastern and western sides by deep Wadis, acquires a particularly interesting character through its crests, which incline towards the Mediterranean—the Gulf and the Kishon. From most points of the crest there is, eastward, an incomparable view over the Bay of Acre and the Kishon plain; westward, over the wide expanse of the Mediterranean.

In true appreciation of the importance of this district, the Palestine Land Development Company has acquired large areas on Mount Carmel for laying out as residential quarters. These plots have been provisionally named Central, West and South Carmel, according to their situation. The total area comprises approximately 6,000 dunams. Photos of the lay-out plans are attached—Pi. 16.

Migdal on the Lake of Tiberias.

The ground of this settlement (Pl. 17) lies on both sides of the highroad from Tiberias to Safed, in the valley extending south and east of the present farm Migdal to the Lake of Tiberias. High mountains bound it to the south, west and north; towards the east the mountains open on to the Lake like an amphitheatre.

The kernel of the settlement, with its residences, bazaar, marketplace and public buildings, lies in the heart of this gorge on either side of the main traffic artery, the Tiberias-Safed Road, whence radial streets communicate with all parts of the settlement. Ringshaped streets connect the various parts together and throw into rhythmical relief yet again the land basin and the amphitheatre of mountains. The backbone of the countryside is provided by a long and wide avenue cutting through the settlement somewhere in the centre. This avenue branches off in the middle into two arms, one leading directly to the Lake, where it terminates in a landing and bathing stage on a broad promenade; while the other arm, in the form of a tree-lined avenue, joins together the two wooded regions and continues to the sports ground and the northern parts of the settlement.

* * * *

The above examples taken at random from a large number of suburban settlements serve to show my intentions under the given circumstances. I am fully aware that even in the schemes on paper a portion only of the problems which garden suburb settlements give rise to can be solved. In view of the uncompromising and rigid attitude of the employers, i.e., the building public, it was, for instance, absolutely impossible to attempt a favourable solution architecturally of the small apartment house on the lines of the attached houses. We are also still far from solving many other aspects of this question. Various difficulties and obstacles confront the actual execution. Similar circumstances prevail in the matter of urban settlements; they are only briefly discussed here.

II. URBAN SETTLEMENTS

General Remarks

Two distinct lines of procedure can be traced in the development of urban settlement. The expansion of existing towns is the one usually followed. The second method, the construction of a town from the beginning, is rarely attempted anywhere, so few town-builders receive the opportunity it affords. As referred to above, one town has in recent times been freshly built in Palestine, namely Tel Aviv, near Jaffa. In the course of 15 years it has grown up from a small garden suburb into a township numbering to-day more than 40,000 inhabitants. Unfortunately, this town was not built according to a coherent plan and, therefore, shows all the serious defects resulting from such anarchic procedure.

The limited number of places in Palestine predestined by their position to evolve into urban settlements, after a certain point of progress has been reached, is not hard to recognise. One such spot is that on which the town of Afuleh is laid out and is now being built in the heart of the Emek (Pl. 18, Pl. 19 and Pl. 20), where the station Afuleh stands at present.

I was instructed to work out the general plan for this town, of which I give a brief description below.*

* Compare with full Commentary to the Town Planning Scheme of the Emek Town, May, 1925

Preliminary Conditions for Planning and Development

Most urban settlements have to come into being in response to an economic need. This alone imbues the town with life and the chance of expanding. The point at which the Emek town is planned to stand answers these requirements; so that its progress must follow in due course.

There are two aspects, which will be the determining factors for the rise of a town at this particular spot. Firstly, south-to-north trade routes will intersect here the most important trade routes running west to east. Secondly, it is the central point of an extensive and fertile agricultural Hinterland, the plain of Megiddo and of the Emek Jesreel. When they are laid down, the west to east traffic arteries will be of special importance. After the harbour at Haifa is built, they will form the simplest and easiest means of communication from this part of the Mediterranean coast through Palestine to the countries of the East. To-day the railway from Haifa to Damascus already passes Afuleh. Once these fundamental conditions governing the future economic development have been made fast the growth of the town will be able to follow as a matter of course.

The plan had thus to provide for these two fundamental conditions, i.e., for the future importance of the place as (a) the most important trade junction, and (b) as the economic centre of this region.

For gaining a thorough knowledge of the potentialities of such a town and incorporating them in the plan, an exhaustive study of all the factors would have been necessary. Such procedure is a matter of course and comparatively simple, when it has as its object an existing town, and when the careful statistics of years are available. Obviously, it is far more difficult to procure such data in the case of a town still to be founded; and unfortunately it proved practically impossible in the case under discussion, because many factors had to be reckoned with which, apart from their not being and not having been, available in statistical form, cannot even be foreseen to-day. In this respect, therefore, the plan had to be based on more or less vague assumptions.*

* These questions are exhaustively dealt with in the Commentary to the Town Planning Scheme of the Emek Town, May, 1925.

If, on the one hand, statistical data are admittedly not procurable, on the other hand it is satisfactory to note the presence of certain factors which determine the planning and structure of this town. Its geographical position and its general economic possibilities settle in advance the form of the whole undertaking. Chief consideration must be given to the main functions of the town, both as a traffic junction, and as the centre of an extensive and fertile Hinterland. More so than elsewhere must the organism of this town be kept elastic enough to allow of future expansion, the extent of which cannot be foreseen as yet.

In this connection quite special attention must be drawn to the style of the foundation of this town, which made the plan an exceptionally difficult one and only allowed the town planner to do his best under adverse circumstances. The land round Afuleh was acquired by the two abovementioned Societies, the American Zion Commonwealth and the Meshek, for the purpose of being divided into plots, sold and developed. Within the residential radius of the town an average size for each plot was determined upon from the start, precluding a more or less stepped structure of building and, with that, variety in the types of edifices. In spite of these hampering circumstances an attempt had to be made to introduce such a graduation and differentiation in the style of building, in some parts of the settlement at least, if only to serve as an example. Further, the land purchasing companies from the very beginning limited the space available for public purposes to 33 per cent. in the southern part of the town, a percentage which had shrunk to 15 per cent. in the north-eastern portion. In view of these circumstances, there was no choice left to me but to either let things take their course and have another Tel Aviv, or to do the best under adverse conditions, in the hope that better counsel might prevail later on, especially in the matter of green spaces. Though I considered the second the more difficult and responsible attitude I adopted it.

Town Planning Basis

The governing factors which predestine this town to be a centre for transport and trade, require it to be a decidedly central town, which radiates its means of communication and develops its districts centrifugally, from the heart outwards.

Means of Communication

The present means of communication comprise the railway line running from south to north in the direction Nablus-Afuleh, and the line running from west to east, that is, from Haifa to Damascus, as well as the south to north main thoroughfare of Palestine, which runs from Beersheba via Hebron, Bethlehem, Jerusalem, Nablus, Afuleh to Nazareth Tiberias and Syria. The principal direction and alignment of the future thoroughfares can be fairly anticipated to-day, as, for example, the west east road from Haifa to Damascus and the diagonal highroad from Jaffa Tel Aviv to Afuleh and the Lake of Tiberias. A radial system of streets provides quick and convenient communication between the town and the entire hinterland.

This, being a commercial town, it was obviously right in this case to place the main railway station in the heart of the town, the geographical features of the settlement favouring its position here, where it will create no interference with the traffic in the town itself. The site selected for the station is situated on the watershed between the Mediterranean and the Jordan, i.e., the Dead Sea, at a height 7 metres above the point where the railway line enters and leaves the confines of the town. This railway (Pl. 19), which it is intended to electrify, is consequently run quite naturally in a cutting below street level, which not only means a horizontal system of stations, but above all, allows the spanning of the main streets by bridges without embankments or cuttings, with a minimum of interference with the town’s building activities, ensuring at the same time close and uninterrupted communication between its northern and southern sections. Structurally this is also to the advantage of the station itself, because in accordance with the most modern building methods, the subsidiary platforms thus come to lie below the main platform. The station is right in the middle of the town, easily accessible from its southern and northern parts. East of the station, near the industrial quarter, are the shunting and local goods stations. A separate goods line from the east, with branch lines, serves the various industrial sectors.

Town Sectors

In planning the organism of the town an attempt was made to fit the various sections into a harmonious whole, in keeping with the main objective. In all its parts this organism has to function rationally and smoothly, just as the human or animal organism, or the organism of a machine depends on each separate part for the proper functioning of the whole. To achieve an artistic organism of this kind is the art of town planning.

Commercial Quarter

In pursuance of this elementary demand the commercial sector had to be as central as possible, in this case it had to form the centre of the town. Traffic being its most vital and important concern, the commercial sector will include the main traffic centre, i.e., main railway station and the main street traffic junctions. The most important commercial undertakings will be grouped around the traffic junctions and along the streets in the inner part of the commercial centre. In planning the more densely built sectors, special attention was devoted to the streets running as far as possible from south to north, thus forcing the buildings in the same direction and ensuring the best possible light and the best possible ventilation by the prevalent cool west wind.

Industrial Quarter

The most favourable situation for the industrial sector was found to the south of the main railway line (goods station) and east of the Afuleh-Nablus line (Fig. 13). This spot seemed to combine all the qualities guaranteeing its future development. The whole area is practically level, with easy access for the sidings and direct connections. The industrial section being in the eastern part of the town furnished the best protection for the other parts from smoke and fumes, because the winds come from the west. Normal expansion to the east has been provided for.

Contrary to the principle in vogue to-day with its more or less mechanical parcelling out, the general plan of the town provides for a schematic sub-division of the industrial sector. The streets, as well as the railway connections, form a complete system of their own, culminating in a square at the southern end of the industrial sector where the public buildings, among others the Post Office, are placed. The division is arranged in such a way that provision is made for industries with large space requirements as well as for those with medium and small space requirements. The latter lie mostly towards the centre of the sector, while spaces for the bigger industries are reserved on the outskirts. The sidings run into the centre of the blocks, finishing off at the outer boundary of the plot. The points where they cross with the streets are reduced to an absolute minimum. A green space separates the industrial sector in the west and the south from the adjoining districts. The sector for small industries is also in the eastern part of the town directly adjoining the commercial sector north of the shunting station.

This method of opening up the two industrial sectors seems to be not only the most rational, but, at the same time an attempt to fit them harmoniously into the general scheme.

Residential Districts

The residential and mixed districts form an organic adjunct to the centre of the town. In their turn they are divided up between the principal streets into private roads, courtyards, green belts and squares. Particularly in planning and shaping the residential districts, did the Companies’ decree of four dunam to each lot prove the greatest stumbling block. The limitation almost endangered the organic structure, particularly as it may be assumed that a round 80 per cent. of all the dwellings will be of the smaller type required by workmen, minor officials and the middle class. To ensure the opportunity for this style of building later on, the plan was framed with a view to allowing the average four dunam plot to be sub-divided into residential streets and blocks for the erection of small dwellings. Special attention was paid to this point in the vicinity of the industrial sector, as workers’ settlements will necessarily have to be established here. All these precautionary measures, however, cannot avert the risk of the premature sale of single plots, and thus prevent these districts from serving their actual purpose. It must be stated with regret that the most earnest protests have proved unavailing.

Public Buildings

The communal buildings epitomise the economic, cultural and social life of a town. They are, therefore, to be found at its most prominent points. Buildings serving economic and administrative purposes will be found close to the working sectors with its key positions, the north and south railway stations, while those of a cultural nature will be placed as near as possible to the residential quarters and green spaces.

Green Spaces

The green spaces are an organic part of the town scheme. Green strips, mostly terminating inside the building blocks, radiate from the centre and form an outer belt of parks. A ring-shaped green belt serves as a connecting link. At the points where the green spaces intersect the radial strips, large green spaces provide freedom from dust and noise for schools, Kindergartens and other public buildings, serving also as recreation and play-grounds. The main cemetery of the town will be near the southern green belt, with a large park adjoining. The children’s play-grounds will form part of the green spaces scheme of the town. At its southern and northern end space has been provided for two sportsgrounds.

As mentioned above, the provision and execution of a green spaces scheme was considerably hampered by the building companies. Large and additional green areas in the town itself, more particularly, however, on its outskirts, must be insisted upon.*

* See details in the Explanatory Report of the writer on the Emek Town Planning Scheme.

The construction of this town, whose plan was only completed last Spring, is already proceeding. Obviously the duty of the town planner does not stay at the drawing up of the plan. He naturally tries to ensure the healthy development of the organism he has created. As the circumstances of the case under discussion are too complicated to allow of more than a brief description, one question only of this kind will be dealt with, namely, the point of departure for building operations.

Experience has shown that although a town may commence to grow centrifugally from the centre, it is apt to skip certain stages, growing into a more or less disconnected and fragmentary structure. To prevent a sickly growth of this kind, all energies must be bent on ensuring a sound economic and organic development from the very beginning. Development along certain lines can only be ensured by its inevitable nature being recognised and deliberately kept to from the very start.

Applied to the Emek town this means that the natural point of departure lies to-day at the station on the Jerusalem road. Near this point the building plan provides for the commercial, industrial and residential quarters. Starting from this point, the town would extend, radiating centrifugally to the adjoining region, its growth similar to that of a crystal.

The economic conditions as described above do not exist as yet, or at any rate only in their initial stages. Any attempt to force the natural pace could, in our opinion, only result in a limited, more or less artificial development, and this only if it were possible to establish already productive concerns on a fairly large scale. They would at any rate create a certain amount of activity, preliminary to becoming part of the normal life of the town.

III. AGRICULTURAL SETTLEMENTS

Probably the hardest problems confronting the Zionist Organisation in respect of colonisation, were those of agricultural settlement. Such problems have a general and a special character.

Some of the most important problems in this connection are best described by Dr. Ruppin, founder and director of the Agricultural Colonisation Department for the last seventeen years, in his book “The Agricultural Colonisation of the Zionist Organisation in Palestine.” (Publishers: Marlin Hopkinson & Co., Ltd.)

“In the very early stages of the Jewish national movement it was recognised already that agriculture would have to form. the economic basis for Jewish immigration into Palestine. One can find clearly expressed in the writings of Hirsch Kalischer (about 1860) and in the first utterances of the Choveve Zion, that the return to Palestine must at the same time mean a return to the soil. Very few people, however, had, at that time, a clear understanding of the immense difficulties with which this necessity would confront the Jewish people.

In the countries outside Palestine the Jewish population is composed in such a way as to resemble a pyramid whose broad base is formed by merchants, their employees, and commercial middlemen. These are followed by industrialists, by professional men (doctors, lawyers, engineers, teachers, journalists, artists, etc.), and by artisans (especially tailors, bootmakers, tinkers, glaziers and goldsmiths), and it is only when we reach the narrow apex of the structure that we find farmers and industrial labourers. The order of this pyramid must, in Palestine, be exactly reversed, if agriculture is to be the foundation of economic life. That which forms the apex outside Palestine must now become the base. This means a radical transformation of occupations, which in itself is extremely difficult and lengthy; but it is all the more difficult, if this transformation goes, as in our case, hand in hand with the need of becoming accustomed to a different country, a different climate, and a different language.

But the fact that, in Palestine, the Jews will have to compete with a people of a much lower standard of life is, indeed, far worse. The whole Orient is characterised by a frightful exploitation of human labour, particularly that of women and children.”

In his introduction Dr. Ruppin mentions a few of his fundamental ideas, of which I wish to quote the following :—

” 1. That for the success of the Zionist colonisation, sociological no less than economic factors have to be taken into account.

2. That the peculiar nature of the problem, which is to bring back townsmen, and Jewish townsmen, to agricultural life in Palestine, renders a solution on the lines of any existing model impossible, and necessitates the application of new methods.

…

4. That the great sacrifices demanded by the work of colonisation are repaid not only by the immediate results, but by the fact that the experience acquired in the process is the indispensable basis for colonising on a larger scale in the future.”

These fundamental ideas underlying the agricultural colonisation of the Zionist Organisation are naturally bound to have an influence on the planning of the settlement. Added to this, the architect has to contend against the peculiarities of the climate, and often those of the land.

As regards the general problems of town planning in connection with agricultural colonies, mention shall be made only of the fact that when these were started upon no proper data were available; like elsewhere, agricultural settlements in this country were rarely built according to plan, even where a plan existed. The well-known European rural settlements had mostly been superimposed on the historic village in course of time, as the need arose, and could not be taken as a model; they are collective settlements, villages where the houses stand in a cluster or are placed in rows with the farms more or less touching, or they are scattered settlements barely hanging together. The American agricultural settlements are mostly of the latter type, their advantage lying in the small distance separating the homesteads from the fields. But they also have the great disadvantages attaching to the scattered settlement, namely a very far flung and expensive system of roads and water supply, difficulties of social intercourse, inconvenient distance from all public buildings, and difficulty in meeting measures of public safety. Settlements of this type, perhaps best described as the type of absolute decentralisation, seemed utterly unsuited to Palestinian conditions. The other extreme type (village cluster), a highly centralised type, did not seem suitable here either for the smallholders or private farmers’ settlement. The ideal type to be aimed at for a mixed farming settlement would be a semicentralised one, combining the advantages of the scattered and collective settlement type, while avoiding its drawbacks as far as possible. The advantages of a type of this kind are obvious: adjoining the farm with the dwelling-house, stables, sheds, tool out-houses and granary is the land which is to be intensively cultivated with vegetables, vines and orchards, all of which need constant supervision from the dwelling-house, while the land to be extensively, cultivated (fields) on which seasonal work is done, lie around the settlement. The settlement itself is closely knit, and the length of the roads reduced without undue crowding; this facilitates social intercourse and leaves the communal buildings conveniently near. Nor does the question of taking measures for security oiler any appreciable difficulties. This type also lends itself far more easily to a compact architectural effect in contrast with the scattered type of settlement.

The selection of a site on which to erect the agricultural settlement is exceedingly important. The ideal place would be in the midst of its cultivated fields on a moderate hill with good land for growing garden produce, near a spring, a main road, and, if possible, a railway station, open to the cooling summer breezes from the west and at a distance from swamps, the breeding places of the Anopheles (malaria pest), which, should any be found at the place chosen for settlement, have to be exterminated prior to its establishment. In practice it is not always possible to reach this ideal, and it is the duty of the Settlement Commission to select the best site they can.

Sociological Structure

Our colonising activities have a character quite their own, which is reflected in the architectural structure of the settlements. The reason for this is to be found in the type of Jewish pioneer inhabiting such agricultural settlements as I have so far planned for the Zionist Organisation. Not only does their longing to till the soil point the way to it, but it is to them, with their deep conviction of the need to till, more than to other sections of the population, that the resurrection of the Jewish people owes its soul. It is, therefore, natural that questions of social ethics play a dominant role. From the Single Workman’s settlement (Moshav Ovdim) to the truly cooperative settlement groups (the large Kvutza and the Gdud Avodah) these incentives are at work in unmeasured degree.

Common to all the settlements is the ownership of the land by the community, the Jewish people through the Jewish National Fund. The settlers, in this case the workers’ communities, receive the land on a long hereditary lease.

The two main settlement types of this kind are those of the Moshaw Ovdim and the small, or large, Kwuzah.

Moshaw Ovdim (Workers’ Village).

In its present form the Moshaw Ovdim is based on the principle of mixed farming, embracing cattle-breeding, dairying and dairy products, poultry rearing and intensive and extensive cultivation, i.e., vegetable growing, viticulture, the raising of cereals, fruit and fodder, and afforestation. Every individual settler is allotted a total of 100 dunams (1 dunam approximately 900 sq. m.), of which roughly 10 dunams are taken up by the farm and the kitchen garden, while the remaining 90 are used for extensive farming. The original type of the Moshaw Ovdim comprised approximately 80 families, with 100 dunams of land each, and about 20 families whose occupations were not agricultural, such as artisans, teacher, doctor, etc., with an allotment of about 5 dunams each to provide for their own requirements. Although in a settlement of this kind every settler works his farm individually, because this way seems to offer the most satisfactory and fruitful scope for his enterprise, in all other branches of the work, as also in the life of the village, the social idea predominates. Thus the purchase of food supplies, tools and agricultural stocks, and the sale of the produce, are undertaken in common through the ” Mashbir ” the Buying and Selling Cooperative Society of the organised workers (Histadruth Hapoalim). The Moshaw Ovdim has a cooperative dairy; the agricultural machinery is purchased, owned and used cooperatively. One of the important basic principles of the Moshaw Ovdim, to which it owes its name, is the principle of the settler working his farm himself (in Hebrew: Avodah azmit). This aims not only at attaching the Jewish farmer to the soil, but beyond and above that, at preventing any form of exploitation of hired labour. Only the settler and his family work the farm. Their 100 dunam of land and their cattle-rearing is not more than they can manage by themselves by dint of hard work, and suffice, if well worked, to ensure a good standard of living.

Practically all the agricultural settlements referred to below lie in the Emek Jesreel (Plain of Esdraelon). The first Moshaw Ovdim, established at the beginning of 1922, shows all the most typical traits and will, therefore, be dealt with somewhat more fully here.

Kfar Nahalal (” The Promised Village”).

The Moshaw ” Kfar Nahalal ” (Pl. 20 and Pl.21), so called after the old biblical name of a village near by, is placed on a gently rising ovalshaped hill in the midst of an exceptionally fertile plain near two springs. The chief road of approach to the Moshaw leads from the Haifa-Nazareth highroad direct to the summit of the hill, which is the central spot of the settlement. Following the contour of the hill, a circular road was built, the farmsteads being placed on its outer side. In the heart of the settlement, on the highest point of the hill, are found the most important cultural and economic communal buildings, crowning the settlement and at the same time outwardly embodying the principle of cooperation. Here stand the Beth Hawn (People’s Institute), the school, a small hospital, the central dairy, stores and sheds for agricultural produce and machinery, the Mashbir, etc., concentrating at its central point the life of the settlement. Streets or paths radiate from this point to all parts of the settlement. Between the ring formed by the farms and heart of the settlement, are placed the five-dunam homesteads of the teacher and artisans. According to the original plan two avenues were to lead from both gardens of the school and the Beth Haam to the foot of the hill, where a strip of fruit trees encircles the Moshaw.

In this way it was sought to create a living organism with a natural culminating centre in harmony with the spirit of this particular type of settlement.

Kfar Jecheskiel.

The principle underlying the structure of this Moshaw (Pl. 21) is very similar to that of Kfar Nahalal and will, therefore, only be described briefly. The appearance of the settlement is less compact owing to the different character of the ground. Here, too, the centre point is to be the village green with the communal buildings grouped round, whence roads radiate in all directions, including the main road leading to the railway station Ain Harod and to the settlement of that name, another road to Merchaviah, to the Emek town and to the Kwuzah Geva, apart from local roads of communication. A circular road encloses the semi-circular plateau on the southern frontal side of the Moshaw, continuing to the gently rising ground and inter-connecting the various radial streets. Here, too, the grouping of the settlers is similar to that of Nahalal, except that some farmsteads are situated alongside the radial roads.

Kfar Hittin.

This Moshaw (Pl. 22) is situated on a hill surrounded by mountains on the western bank of the Lake of Tiberias. The view over the Lake and the opposite bank, from the eastern part of the settlement, is of surpassing beauty. As this is the only part of the settlement which can be seen from the Lake, space was reserved here for a few public buildings, such as the synagogue, the hospital, the hotel, etc. Their naturally advantageous position will be enhanced by a park which is already being laid out along the mountain slope. Communal buildings demanding a more central position will be provided for in the centre of the settlement. The streets and buildings gravitate towards this culminating point. In this plan details with regard to the individual farmsteads were marked for the first time.

Moshaw Transylvania.

This Moshaw (Pl. 23) takes its name from the pioneer group, whose members were for the most part farmers in Transylvania. These people insisted on the settlement being constructed on both sides of the main road (Jerusalem-Emek town-Tiberias) as is the custom in their native country. A demand of this kind was bound to create difficulties of a peculiar nature. The danger to life and limb on so crowded and busy a thoroughfare was very grave indeed, and the penetration of dust into the houses had to be guarded against, without interfering with communications. For this reason the farmsteads are accessible by two local roads separated from the main road by broad strips of trees. Only at three points—the centre, the entrance, and the exit—has this line been broken. Along the main road trimmed hedges prevent man or beast from crossing the road except at the points indicated. At the entrance or exit, obelisques or fountains (illuminated at night) will be put up to compel the slowing down of the traffic, which will be able, however, to proceed unhampered and free from risk at the other points. The trees on both sides of the highway provide additional protection from the dust. Public buildings are placed in the centre. On the roads branching off to the fields, there will be additional farmsteads, thus avoiding the unsuitable and unattractive form of a village with two straight rows of houses.

Herzlia, near Tel Aviv (Pl. 24).

A rural settlement of private farmers. Here the individual settler needs less ground than in the Moshaw with its mixed farming. The method of intensive cultivations, i.e., banana and orange plantations, does not demand more than an average sized plot of 10-20 dunams of land for each settler. The settlement is situated on the hilly part of the ground, each farm surrounded by its garden, while the orange and banana groves are in the hollows or on the large fertile plain extending below the hills. This form of settlement can naturally maintain a larger number of settlers than that devoted to mixed farming.

The Kwuzah (Cooperative Settlement).

The Kwuzah (literally: a group) is distinctly a cooperative form of settlement. The cooperative principle finds expression in all aspects of daily life. The children grow up together, live and feed together. The families live in communal houses, taking their meals in company. It seems necessary to state here also that this communal life not only does nothing to loosen the bonds between parents and children, but, if anything, seems to draw them closer. The children are the first concern of every Kwuzah, the whole community striving to provide the best possible conditions for them at the cost of heavy sacrifices.

The joint ownership of all animate and inanimate stock, and the application of the cooperative principle to life and work naturally express themselves also in the structure of the settlement. If the Moshaw may be compared to a village, the outward appearance of the small Kwuzah (30 to 50 families) rather resembles a large farmstead, and the large Kwuzah (199 to 200 families) the large farms, similar to those of North America. Below a few examples are given of the planning of large as well as of small Kwutzoth.

Kwuzah Hagevah (The group of the Hill).

In planning the groupments of the individual farmsteads of a Kwuzah, the essential point is that its main parts should form an organic whole, thus retaining the interconnection between the individual parts. The farmyard of Kwuzah Hagevah, a settlement on a northern hill in the Emek Jesreel, can be taken as a typical example of its kind.

The main feature of this settlement (Pl. 25) is the large farmyard placed to the east of the dwellings, by which means the predominating west winds blow from the house to the stalls and keep off flies and stable odours from the house. West of the farmyard is a dwellinghouse with garden, and the Children’s Home with its garden. Inside the farmyard, hard by the entrance, there is a small separate yard for carts, machine and tool sheds and workshops.

Seeing that the position of the farmyard in a Kwuzah, even more than in the Moshaw, determines the position of a number of more or less large buildings, special attention should be paid to the need of giving all buildings, destined for the permanent housing of men or cattle, a longitudinal axis approximately south to north, or in a vertical direction to the cool breezes. In this way cross-ventilation and plenty of sun is assured; with the buildings facing in the direction mentioned the comparatively mild eastern and western sun reaches their broad side, with only the narrow southern side exposed to the hot mid-day sun. The necessity to provide a position of this kind complicates the planning, because in nearly every case buildings of this nature are bound to predominate. The farmyard must, therefore, be planned in such a fashion that all the buildings, to which the above conditions do not apply, can be placed on its northern and southern sides, at the same time fitting them as well as possible into the general plan. Such an arrangement is facilitated by the fact that the poultry yard needs not only the southern sun, but also protection from the cool western breezes.

In accordance with the conditions set forth above, the living quarters for adults and children, and the children’s garden, have been placed in the western part, the poultry runs in the north, i.e., towards the farmyard open to the south, the cowsheds and stables, as well as the granary, in the east, while space for workshops and sheds has been reserved in the south. The kitchen, where work goes on uninterruptedly all day, commands a view of the whole yard. The communal dining room adjoins the kitchen. The one is moved out of the building line of the other, the dining-room being somewhat higher, so as to allow ventilation by the west wind.

To the west of this central point are situated the vegetable and the children’s garden, poultry runs to the north and yards for cows and horses to the east.

This plan provides for 20 families, 60 children, 1,000 chickens, 50 head of cattle, 20 horses.

Kwuzah Ain-Harod and Kwuzah Tel Joseph.

These two large Kwuzoth are situated on the southern slope of the Kumie hill in the northern part of the Emek Jesreel. This hill is the most prominent point of the region. Rising approximately in the middle of its northern part it is visible from all parts of this fertile valley. Accessible on the one hand to the cool western breezes, and on the other hand lying comparatively high, it represents the healthiest and most beautiful, therefore the most favoured spot of the whole region. Yonder, where the southern part of the hill slopes down gently to the cultivated fields of the plain, the two large Kwuzoth, Ain Harod and Tel Joseph are to be established, Ain Harod west of the Wadi (mountain valley or river bed containing water only in the rainy season), and Tel Joseph east of the Wadi. According to the plan, the space provided for Ain Harod is to accommodate 200 families, 300 heads of large cattle, 50 head of young cattle, 80 horses, 600 sheep and goats, 7,000 hens and 15,000 chickens; ducks, geese and bees.

For Tel Joseph the accommodation will be for 150 families, 250 head of large cattle, 80 horses, 500 sheep and goats, 2,500 hens, 5,000 chickens, 500 ducks and geese, and bees, to which must be added space for locksmiths’ workshops, a smithy, a carpentry, cartwright’s shop, sheds for agricultural implements, carts and machinery, lofts and store-rooms, as well as an area to the south near the railway station destined for the erection of buildings for an agricultural industry.

Ample possibilities for expanding the farmyard to east and west are provided. The top of the Kumie hill is to be crowned with communal buildings. Its steep, southern, eastern and northern slopes are to be afforested. Space has been reserved on the summit for the general Workmen’s Hospital (belonging to the Workmen’s Sick Fund), as also for a central school. Later on, a large common building for all the agricultural settlements in this region is to crown the topmost point of this, the most unique and beautiful mountain summit in this part of the plain. A building which will serve as a rallying point for and as a symbol of our best agricultural settlements.

To go into more detail would lead too far. The accompanying sketch represents a project which still requires revision. It is given in its present form merely to demonstrate my layout for large Kwutzoth.

Beth Alpha.

This (Pl. 25) is the most eastern settlement of the Emek and lies at the foot of the Gilboa mountains. Here, as well, two Kwutzoth will be established side by side, a large one, the first group of the ” Kibuz ” in the east, and a small one, the Kwuzah ” Chefzibah ” in the west. The position of the hill itself is not very favourable, being comparatively low at an altitude of 85m. below sea level already in the depressed zone of the Jordan source, but unfortunately no better place was available. The position of the hills has determined that of the settlements. The communal buildings, in this case the school, the Kindergarten, as well as the children’s quarters with the green strip for the garden towards the north, lie between the two settlements. To the east and to the west the outer slopes of the hills offer ample opportunity for future expansion. There are two alternatives for building a main road outside the settlement; either on its northern or on its southern side. The groups of dwelling– houses adjoining the school compound east and west are on the highest point of the flatter part of the hill. It seems worthy of note that the eastern Kwuzah is about to raise cattle on a large scale.

* * * *

We are far from claiming that the plans sketched above represent the last word. In the same way as the conception and the working plan of the Moshaw and the Kwuzah are intended to produce maximum utilitarian results, do the above designs try to adapt themselves as best as may be to given conditions. Just as we shall go on trying to improve our farming methods, so will the endeavour have to be made over and over again to attain to the best possible results in laying out the settlements, and in making the plans elastic enough to admit of innovations.

IV. REGIONAL PLANNING, &c.

In the foregoing I have dealt with the town planning of various types of settlement in Palestine. Formerly there was no scope for regional planning on any large scale. Opportunity for it has only arisen through the acquisition in 1925 of a large connected area along the Bay of Haifa Acre, of approximately 20 km. This area (Pl. 27), and its adjoining districts, totalling 100,000 dunam (ca 10,000 ha) it is at present my task to work upon. In view of the above-mentioned prominent and exceptional position of Haifa, in relation to the Near East in general, and to Palestine in particular, the area will in all probability undergo the most varied and intensive stages of development of any in Palestine. As the designs are only in course of preparation now, no details can be published yet.

Architectural Projects

I also show two architectural plans which I have made for the electrification project of P. Rutenberg, Engineer, namely the power stations at Haifa and Tiberias, both in reinforced concrete (Pl. 26).

Execution of Town Planning Schemes

The above remarks were to serve as a commentary on my town planning schemes for various settlement types for the new Palestine. They were not meant to furnish data for carrying out the plans. This would have been distinctly premature, seeing that the settlements are being extended gradually, and are still to-day more or less in the building stage.

For that reason, it should be said here that the problems presented by the execution of these plans are as manifold as they are difficult. And as the town planner may not confine his activities to the mere working out of the plans, his task is of a very exacting nature. But this, too, does not fall within the scope of the present article.

I do not wish to conclude these remarks without grateful mention of my fellow-workers, in particular my colleague of many years, the architect, Miss Charlotte Cohn.

RICHARD KAUFFMANN.